|

|

|

|

Chapter XVIII

Work And Play In Later Years (cont.)

|

|

If it were possible for a house to be jealous, Slabsides would be

jealous of Woodchuck Lodge, for since 1908, every summer and until

late into the fall, the Hermit of Slabsides has forsaken his woodland

cabin for a little farmhouse on the home farm near Roxbury in the

Catskills. For two summers he simply camped out there with friends,

but in 1911 made certain improvements, so that it has since been a

comfortable midsummer home. Its roomy veranda, which admits of

several cots, is a sleepingporch by night and a living-room by day.

In the orchard above is a little Bush Camp where he writes and dreams

and looks off toward Montgomery Hollow. But oftener he writes in the

old hay barn up the road, looking off into the woods that lead to Old

Clump, and, like Thoreau, happiest the mornings when nobody calls

(except a red squirrel or a chipmunk). In the afternoon he welcomes

the friends who come from far and near to see the Laird of Woodchuck Lodge.

The "Barn Door Outlook ... . A Hay-barn Idyl," " In

the Circuit of the Summer Hills," and most of the essays in The

Summit of the Years, in Time and Change, in The Breath of Life, and

in Under the Apple Trees have been written either in the Hay-barn

Study, or in Bush Camp.

One summer when an artist was painting his portrait in the barn. a

junco built her nest in the haymow close o them, thus beguiling the

otherwise tedious time to the restive sitter. One summer, on his

Boyhood Rock, he sat to Pietro, the sculptor, for a larger than life

statuenow a superb bronze in the Art Museum in Toledo. During the

sittings various members of the household were called up there to

read to him and sometimes to help support his arm, the pose calling

for one hand to shade his eyes as he looked across the wide valleys

to distant Catskill peaks. As the clay statue grew to be almost a

living thing, we used to feel guilty at leaving it up there exposed

to cold and rain. One morning the sculptor found to his dismay that

the cows had eaten away a part of the foot and ankle of the clay man.

The sitter's concern, however, was chiefly lest the clay sicken the cows!

Woodchuck Lodge was so named because of the great number of those

rodents that burrow in the fields and hillsides, and pilfer in the

garden. "We are beleaguered by them," Mr. Burroughs often

tells his callers, "and are forced to shoot them in

self-defence." A youth who asked one summer if it was called

Woodchuck Lodge because he protected the woodchucks, was somewhat

taken aback by the reply, "No, but I'm going to make them

protect me from the cold this fall." And leading him around to

the woodshed, Mr. Burroughs showed him upwards of eighty marmot

skins, home-tanned, stretched and drying on boards, and on the side

of the house, some of which later went into a large rug for his cot,

as others before had gone into rugs for the veranda floor. The

choicest of the skins, after long hours of preparation-skinning the

skin, and treating it with lightning tanner-were sent to a furrier

and made into a handsome coat. While selecting and packing those

skins for shipping, we heard him say alf to himself: "I shot him

by the rock-that's the little cuss that got drowned out-these are the

two big fellows I got below the orchard, so heavy I could hardly

carry them up to the house-that's the black customer that came from

Rose's Brook-he might do for collar and cuffs." People often

marvel at the keenness of sight and surety of aim of the octogenarian

Nimrod, and are staggered at the proof of his prowess.

After many years of living at Woodchuck Lodge, we learned how to cook

the creatures so they are really a savoury dish. Hamlin Garland, who

sometimes comes over from Onteora, feels aggrieved if a 'chuck is not

on the bill of fare during his stay. Other guests, who, on being

served with 'chuck, sit down to sniff, remain to pray for more.

One day a caller, looking at the nearly finished statue previously

mentioned, said in awed tones, "It seems symbolical, as well as

being an excellent portrait-he is looking over a vast area, from a

height far above the rest of us -what is that vision he beholds?"

"Most likely a woodchuck down in the beechwoods," retorted

the sitter. And it is true that when posing for the statue, he would

jump up unceremoniously and, gun in hand, march to a distant field,

wait patiently if need be, and soon the crack of his rifle would tell

us he had got it, or not, as the case might be, when he would come

back and resume his pose.

There is much wild life to be seen on the old farm besides

woodchucks. One day last August I saw J. B. coming toward the house

with a long pole over his shoulder, a very long pole, at the end of

which hung a skunk with foot caught in a trap. Now gingerly he

walked, how carefully he deposited his burden, letting it down

slowly, almost reverently, into a barrel! At this stage everybody

fled. He succeeded in releasing the creature's foot from the trap,

but how should he get rid of him? Very carefully he laid the barrel

down on its side, but the skunk hugged it closely. In most

ingratiating tones he tried to coax "poor pussy," "nice

pussy," forth, but to no purpose.

Sir Mephitus would take his own time. In the morning the barrel was

empty, and no harm done. I have seen Mr. Burroughs carry a skunk by

the tail, but of course the trick is to get hold of the tail in time.

There have been times when the experiment has terminated less

favourably; then I have quite appreciated the name given the creature

by a Scotch lassie who, shortly after coming to America, ran in to

her mistress and told her the hired man had killed a stunk (sic.)

Mr. Burroughs is proud of his Catskill garden. He hoes in it

diligently and fairly gloats over the telephone peas, the golden

bantam corn, the Hubbard squashes, and other produce. One season a

vine yielded him one hundred and forty-five pounds of squash. On

sending Mr. Edison one of the biggest fellows, he asked him if he

thought Mother Hubbard ever had anything in her cupboard to beat that.

One moonlight night in October, a few years ago, Mr. Burroughs

was awakened by a strident cry under the hill, about one hundred

yards below the veranda on which he was sleeping, the like of which

he had never heard before. It was so loud that it echoed in the woods

four hundred yards away, tapering off into a long-drawn wail which

for agony of soul, or hopeless longing, he had never heard equalled.

" If a lost soul had been given a few hours' freedom, but had to

be back in Hades on the stroke of midnight, it might let off such a

strident cry and hopeless wail as that." He was greatly puzzled

as to its origin. None of the others sleeping on the veranda heard

it, but the next night, at the same hour, a young couple sleeping

upstairs, awakened by a similar cry, were so frightened they could

not get to sleep again. A few years before, a woman guest and her

son, a lad of fourteen, sleeping in the orchard in front of Woodchuck

Lodge, had been frightened by a strange cry, which had sent them

white and trembling into the house, though then Mr. Burroughs, not

having heard it, ridiculed them, saying it was probably a fox

barking; but when he himself heard this weird cry, he immediately

thought of the one the lad and his mother had heard; and also of the

report, that same year, of some young people on their way through the

woods to a party, being so frightened by a wild, strange cry at

midnight, that they and their horse were scared almost out of their

wits. -The people thereabouts firmly believe these wild cries came

from a panther or puma, and Mr. William T. Hornaday, to whom Mr.

Burroughs described the cry, was inclined to think so, too, --

probably a puma escaped from captivity-but Mr. Burroughs thinks if a

puma were lingering in the mountains, it would have caused some

depredations. That year, shortly after he heard the strange cry, he

learned of a young farmer near him having seen a bob-tailed animal,

as big again as a wild cat, come out of the woods, but as quickly

disappear in them, and he thinks from the description that it was a

lynx, and that that was the creature which, on occasion, makes night

hideous in those peaceful hills by its unearthly cries.

One August day, several summers ago, Mr. Thomas A. Edison and family,

touring the Catskills, motored fifty or more miles out of their way

to call at Woodchuck Lodge, and later Mr. Henry Ford and a party of

six came there to pick up Mr. Burroughs for a New England jaunt,

liking the Lodge so well they tarried several days. And in truth, Mr.

Ford came back many a time after that, always pleased with the truly

simple life of Woodchuck Lodge.

In 1913 Mr. Ford sent Mr. Burroughs a touring-car, and has kept him

supplied with one ever since. He is now using his fourth car. The

Walker took rather more kindly to the "contraption" than

one would think, though having many a narrow escape the first year.

Since he has become reconciled to the fact that one can really trace

a bird's flight through bush and tree better on foot than when

guiding a car, and has given up climbing trees and attempting other

similar stunts with his car, he really enjoys it; and daily climbs in

it the steep hills, on the home farm, the hills up which he drove

oxen as a boy.

At a week-end party at Onteora one October, Mr. Edison told us the

story of the first try-out of the phonograph. After the long hours of

experiment and doubt, enlivened only by incredulity and, ridicule

from onlookers, the inventor and his helpers were at last ready to

test the invention: " When 'Mary had a little lamb,' actually

came squawking out in human tones", said Mr. Edison, "the

men were all amazed-and so was I!"

On someone asking Mrs. Edison if her husband drove his own car, she

laughed outright: "He is the most awkward man with his hands I

ever saw-he would run a car up a tree or in a ditch, if he tried to

drive it."

When he heard his deafness referred to as a handicap, Mr. Edison said

that, on the contrary, it had been a great advantage; it had shut him

away from much that is annoying, and, he added with a twinkle, "I

don't have to hear all the chatter around me, and I'm spared hearing

telephone bells, and phonographs, and all those nuisances." |

|

Driving his car on the farm where he drove oxen as a boy |

When he heard his deafness referred to as a handicap, Mr. Edison said

that, on the contrary, it had been a great advantage; it had shut him

away from much that is annoying, and, he added with a twinkle, "I

don't have to hear all the chatter around me, and I'm spared hearing

telephone bells, and phonographs, and all those nuisances."

Several times in the last few years Mr. Burroughs has taken

auto-camping trips with his friends, Messrs. Edison, Ford, Firestone,

De Loach, and others, sometimes in the Adirondacks, sometimes down in

Dixie. Once in starting out they camped one night in the orchard at

Woodchuck Lodge, their green tents, lighted with electricity (for the

Wizard carried his own battery) making a pretty scene in the old

orchard. The movie men followed them about, and the reporters gave

their own versions of happenings on these jaunts. A Rochester paper

stated that Thomas A. Edison, the great electrician, Henry Ford, the

automobile manufacturer, H. S. Firestone, of the Firestone tires, and

John Burroughs of the adding machine were making a tour of the North

Woods in automobiles! |

|

On these trips Mr. Edison, a light eater, usually lectured Mr.

Burroughs on his more liberal indulgence, urging him to cut out this

and that-things that go down too easily, things that are not heated

to 212 degrees Fahrenheit, things that are too cold, or too something

or other. He cautioned him against sugar because it made crystals in

the blood, and so on. But Mr. Burroughs turned on him for bolting his

food, and eating pie by the yard, and taking black coffee, and

smoking. " Cane sugar is bad for one, is it, Edison? But I

notice you take two spoonfuls of it three times a day in your coffee

Oh, consistency, thy name is not Edison!" And Mr. Edison, like

all truly great persons, acknowledged the corn: "I know coffee

and smoking are bad for me, but I'm usually so good about my eating

that I allow myself these little indulgences."

On returning from the summer outing in 1918 in the Great Smoky

Mountains, Mr. Burroughs confessed that mountains and men who do not

smoke please him far better. He said the wilder and rougher the roads

were, the better Mr. Edison liked them, while he used to beg that

they keep to the smoother roads: "You carry your shockabsorbers

with you, Edison, but have mercy on us thinner mortals!

One day when the fan to the Packard broke and punctured the radiator,

their crew, and the workmen at the nearest garage, shook their heads

and prophesied a long delay until a new radiator could be sent from

Pittsburgh; but Mr. Ford said, "Give me a chance at it,"

and rolling up his sleeves, went to work. With drills and copper wire

and gumption he had the damages repaired in two hours, and they were

off again!

Their last jaunt had the best outfit of all, though the first one,

several years ago-two big cars, two Fords, and two trucks, and a crew

of seven men-was not exactly roughing it as J. B. understood the

term. In fact he called it a Waldorf-Astoria on wheels. In their

second Adirondack trip, in 1919, a special feature was a Cadillac

touring car with a covered body to carry the tents, cots, chairs, and

so on, and a Ford with its body fitted like a travelling grocery,

with drawers for food and dishes, a shelf which would slide out for

the convenience of Sato, the resourceful Japanese cook; with gasolene

stoves attached to the running-board, an oven, and many another

convenience, by means of which they went far and fared sumptuously.

One morning in camp when someone asked Mr. Edison if he would have

some prunes, he replied, "No -- I was once a telegraph operator,

and lived in a boarding-house." Near one of their camps Mr.

Edison handed out nickels to some children hanging about, wide-eyed

and shy as partridges. When someone asked them if they knew his name,

a little girl replied," Yes-Mr. Graphophone." |

|

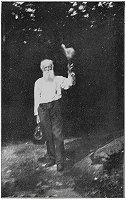

John Burroughs showing Edison glacial marks on

the home farm. |

Mr. Edison is a first-rate vagabond. He could go with ruffled hair

and unbrushed clothes as long as anyone. Around the camp-fire he

delighted them with his fund of stories, and wise and witty remarks.

"He is as full of facts and formulas as an egg is of meat,"

said Mr. Burroughs. "His memory is like an encyclopedia'' One

night in telling them of the difference between white and black

diamonds, and of the extreme hardness of the black ones, found only

in Brazil, he said he had examined one which had been used for

drilling ten miles through volume rock and that under a powerful lens

it did not show the least sign of wear! Mr. Burroughs had known since

boyhood the biting taste of the root of wild arum, or

Jack-in-the-pulpit, but did not know, until Edison told him, that its

stinging effect upon the tongue is a mechanical one, due to tiny

needles of the oxalate of lime. And familiar as he has always been

with the skunk, it was reserved for Edison to tell him the name of

the chemical compound which gives the potency to that odoriferous

secretion. But when the Wizard attempted to dogmatize about Nature,

asserting that in the inorganic world things go by even, and in the

organic by odd, numbers, J. B. slipped away to the edge of the swamp

below their camp and brought back the four-petalled flower of the

galium, with its four leaves in a whorl. And he rubbed it in by

telling him of the dwarf cornel, the housatonia, the evening

primrose, and even of the whole order of the cruciferxae; of the

four-sided stems of the mints; of the six-sided cells of the

honey-bee, and so on. |

|

Mr. Ford was as lively and happy as a boy from mornIng till night,

chopping wood, climbing trees like a squirrel, kicking high,

challenging some one to race with him, alert, hopeful, and good-natured

under all circumstances and conditions. "A very likable

man," said Mr. Burroughs, "as tender as a woman, and much

more tolerant. Practical in all mechanical matters, an unconquerable

idealist, he always seemed to be thinking of the greatest good for

the greatest number of his fellows. He deplored every water-power he

saw going to waste, and wanted to harness all those streams and thus

make life easier for the masses."

The shadow of the Great War rested heavily upon the spirit of Mr.

Burroughs from first to last. Following it with absorbing interest,

he feared he would never live to see its end. Each day as the rural

delivery man came all too slowly up the hill, he would go out to meet

him, growl at him if he were late, seize the paper and devour the

news, Intolerant of any interruption. And when, as so often happened

in those early months, everything seemed going the wrong way, he

would fling the paper aside and rush out to the wood-pile, the savage

blows of his axe the only fit outlet to his feelings. Or sometimes he

would wreak his vengeance on the flies -- "Our grey-crested fly-catcher,"

as one of the family called him.

Long before we as a nation were sufficiently aroused to get in the

War, he enlisted, and with trenchant pen dealt blows which made the

enemy wince, judging from the in insulting comments they called forth

in German newspapers, and the abusive and threatening anonymous

letters which came to him. Such attacks only egged him on. Again and

again in those terrible years, he arraigned the enemy and voiced the

undaunted purpose of the Allies. He returned to the charge again and

again, and even after Germany cried quits, had a few things to say.

Like a boy who has watched a bully get a good licking, but remembers

countless scores that can never be wiped out, he kept nursing his

wrath, declaring, long after the armistice was signed, that when he

tried to think dispassionately of all that Germany had been guilty of

during the War, he found himself getting hotter and hotter. Often

during the war the very peace and repose of his native hills

reproached him, and he turned in vain from one to another of his

accustomed resources to assuage the terrible weight of the world woe.

A pretty episode in the fall of 1915 occurred in his native town, in

the midst of war's alarms. As an interlude in a pageant which

celebrated the pioneer struggles of the More family in that vicinity,

a charming Nature Interlude was introduced in which Roxbury paid a

fitting honour to her Prophet in his own country.

The allegory (told in living pictures) was enacted on a grassy plain

in an amphitheatre formed by the encircling hills, the Pepacton

winding in and around the scene. It showed how Nature veils her

wonders and beauties till one comes who can lift the veils and reveal

mysteries beneath mysteries. Maidens in floating veils of varied

tints and hues, symbolizing spirits of the earth and sea and sky, of

the vales and hills, and of the seasons, disported themselves across

the grassy stage, then sank in slumber and concealment of the grass

as the dreamy music, to which their dancing feet kept time, died

away. Suddenly a hopeful strain was heard, and a bright creature in

golden draperies appeared, wand in hand, symbolizing the Vision of

Nature which it had been given to John Burroughs to behold, her wand

the magic touch he has given to Nature's hidden beauties.

As she glided to the sleeping spirits of the earth and sea and sky,

and touched them with her wand, slowly, gracefully, they arose, cast

aside their enshrouding veils, while in their midst Nature herself

awoke, arose, resplendent, alluring. Then from behind the shrubbery,

summoned by the magic wand, came a joyous flock of birds and

butterflies and all sorts of winged creatures, and creeping

creatures, and hopping creatures, in one jolly, tumbling, skipping

throng. Gliding to a distant point on the grassy stage, whence she

had first emerged, the Vision again beckoned with her wand, and out

from behind the screen stepped the living, moving John o' Birds.

Humbly and reverently he approached the glowing Vision and followed

her down the great green stage. Nature stepped down from her green

mound and flitted and hovered near him, while all the shining hosts

floated round Nature and her Interpreter as, moving across the stage,

they were accompanied by the troops of children disguised as the

dancing, skipping, flying, crawling denizens of land and sea.

During the winter of 1916, while Mr. and Mrs. Burroughs were visiting

in Georgia, they became seriously ill. For him, recovery followed in

a few weeks, but for her it was the beginning of the end, and after a

year and more of wasting illness, in early March, 1917, in her

eightysecond year, release came. They had been married fiftynine

years; they had been young together; together they had lived through

years of struggle and obscurity, her thrift, industry, and frugality

contributing no small share to the material prosperity which marked

their lives during and after the Washington period. For her the long

journey was ended. It could not be long, he reflected, before Mother

Earth would beckon to him also. At sundown, and in the long hours of

the night, he often broods over the Past, and the days that are no

more -- a prey to the dark even as when he was a child in his

Catskill home; but with the rising sun his buoyancy reasserts itself,

and he faces toward the East, toward each new day, still finding life

sweet, still saying from the summit of the years, "The longer I

live, the more I am impressed with the beauty and the wonder of the world."

Journeying again to Southern California, in December, 1919, John o'

Birds spent the winter chiefly in La Jolla, revelling in the beauty

there of sea and sky; watching the pipits and ring-necked plovers on

the lawn; the sea-gulls and pelicans on the shore; watching the hair

seals playing in the waves, whose barking, heard almost any hour Of

the day or night, led him to call them "hounds of the sea"

observing the curious trap-door spiders whose ingenious nests he

found on the beach; climbing Soledad; automobiling in the Imperial

Valley; speaking to clubs and schools; ferrying awhile in Pasadena;

touring other parts of the great wonderland of California; and then

eagerly journeying homeward in the shining days of March to be on

hand for his spring sugar-making. While in California he completed

and sent to the publishers a new volume, Emerson and Thoreau.

"Pacific Notes," a recent magazine article, an outgrowth of

this trip, was also written there.

His eighty-third birthday found him with a jolly weekend house party

at Yama Farms Inn. There he superintended the sap-boiling, planted a

maple tree, walked in the woods, fished in Honk Falls, and basked in

the crisp sunlit April air without, and in the abounding cheer and

hospitality within. Sitting around the fire with his host and a

circle of gathered friends at the close of the day he said: "I

have had a happy life. My work has been my play, and I don't want a

better world than this to play in, or better men and women for my friends."

The birthday festivities ended, he returned home to tackle the

avalanche of accumulated letters, get his new volume (Accepting the

Universe) off to the publishers, and welcome the returning birds. |

|

Good Bye |

Spring is already here at Riverby and celebrating her birthday, too.

Pussy willows and spice bushes along the brooks hint it, skunk

cabbages and spring peepers proclaim it, the toads trill it, the song

sparrows blithely assert it, bluebirds warble it, robins chirp it,

phoebe announces it, the flickers laugh it, even the crows caw iton

every hand the world-old miracle is heralded anew. After a day

replete with tokens of the Spring's new birth, John o' Birds seeks

yet one more familiar evidence-the twilight mating song of the

woodcock. On nearing the swamp we hear at first that harsh Seap . . .

. . . Seap, Seap, as the bird moves about on the ground in search of

worms. Presently the calls cease, and we are suddenly enveloped in a

chippering sound as, rising In wide circles, the bird mounts and

mounts, showering down its rapid, rippling notes, now near, now

faint, now lost for an instant, then near and nearer, more and more

rapid-fine, hurried, ringing sounds ending in an ecstatic burst while

in the zenith, after which the singer drops suddenly to earth and

resumes his prosaic search for food. We wait for him to rise again on

his singing wings, again listen to that joyous downpour, and yet

again-elusive twilight song, born of the passion and ecstasy of

spring! 'But darkness falls, the song is hushed, the stars come out,

and picking our way through the low marshy ground, we seek the light

and warmth and shelter of The Nest. |

|

|