|

|

|

|

Chapter V

Ways And Means In John's Boyhood

|

|

Seventy and eighty years make quite a difference in the customs and

methods of people living in the same locality and following, in the

main, the same pursuits as their ancestors. Our ways and means to-day

seem quite commonplace to us so accustomed to them, but eighty years

hence they may hold a great deal of interest for our children and

grandchildren, just as the way they did things when John Burroughs

was a boy interests us to-day.

BAKING DAY

In those days they could not step out to a grocery and buy a loaf of

bread. It would not have gone far in such a big family. A baking-ten

big loaves of rye and two of wheat-had to be pieced out with

pancakes, Johnny cakes, and biscuits.

On baking-day the old kitchen was all a-bustle. The great brick oven

was heated piping hot before the bread went in, by building a fire in

it where the loaves were later to go. Such a skurrying as there was

among the boys when their mother called for more and yet more light,

flashy wood!

"One more armful-quick!" she cried, when they would think

their job done. Then they watched her as, opening the door and

testing the oven with her hand, she pronounced it hot enough; quickly

raked out the coals and .ashes, and put in the loaves with the

long-handled iron shovel. An hour later, when the big wooden door was

opened, and the brown crusty loaves drawn out-was there ever a more

delicious smell! And sometimes Mother Burroughs cuts one of the warm

rye loaves for her hungry boys-" Um! Um! Guess I don't mind

getting oven wood, after all!"

There was also a little Dutch oven made of tin, closed at the sides,

back, top, and bottom, like a little shed. This was set down with its

opening close to the fire; in this their mother could bake Johnny

cake or biscuit in a hurry, when company came unexpectedly.

DAIRY WORK

Before John was old enough to do any milking, he saved his mother

many steps by helping with the pans. There were about ten pailfuls of

milk at each milking, morning and night; it took four pans to a pail,

so there were forty milk pans to skim and wash twice a day. Starting

to skim about three in the afternoon, it usually took her an hour,

with John carrying the pans. A boy had to mind his p's and q's with

those full pans, Perhaps it is due to that early task that we never

find him "slopping over" in later years.

How deftly his mother skimmed the cream! With a case-knife she would

sweep around the pan, then slip the thick yellow mass, looking like a

leather apron, into the cream-jar. When the milk was

"lobbered" they saved out some for pot-cheese, and ate

some, sweetened with maple sugar, as " bonny clabber," but

the most of it, with the skim milk, was fed to the pigs. |

|

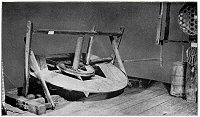

A Dog Churn |

THE DOG-CHURN AND THE CHURNERS

In summer the butter was made by means of the dogchurn - a large

wheel set at an angle, which went round and round as the old mastiff,

standing in one place, would tread it. The cogs on the wheel turned a

shaft which bad a crank, the crank worked the sweep, and the sweep

lifted the churn-dasher. It was a dull, tiresome round, even for a

dog, usually taking half a day. Old Cuff got so he knew when churning

was to be done and at such times contrived to have important business

with the woodchucks in a distant field. |

|

When Cuff quit his job they pressed an old ram into the service, but

after a time he proved fractious, hanging back and settling down and

refusing to make the wheel go round. When that was the case, John and

Eden had to take their turn at the tiresome treadmill. They soon

learned to outwit the balky fellow: Rigging up the hetchel behind him

so that when he started, to settle down the teeth of the hetchel

would prod him sharply, they forced him to do his stunt, willy-nilly.

There came a day when, utterly weary of the many unlucky turns of

Fortune's wheel, the ram decided to make an end of it. He jumped off

the wheel and hanged hi

self with the rope by which he was tied. John and Eden, for reasons,

mourned the death of that ram more than did any others in the

Burroughs household.

(Once when Mr. Burroughs was past seventy I was with him in an old

mansion at Johnstown, N. Y., where numerous implements of auld lang

syne were on exhibition -spinning-wheels, looms, distaffs, swifts,

warming-pans, horse-pistols, and so on-and when some one asked,

"Have you ever seen a dog-churn?" he retorted quickly,

"Yes, yes, and I've been the dog," and fled down the attic

stairs as though afraid of being pressed into service again.)

In winter and early spring when there was less milk, they used a

hand-chum, and two of the boys had to ply that dasher up and down

interminably-work which they cordially disliked. They did not dislike

the delicious buttermilk, though, with the little flecks of butter

swimming about in it, which their mother dipped for them from the old

blue churn after their glad shouts of triumph-" Butter's come!"

CHEESE-MAKING

John's mother made cheese only three or four times a year; they could

not afford it oftener as it took a whole milking.

Into the big kettle of milk went the rennet (the dried stomach of a

calf) to curdle it. When it was a solid curd, John would dip out the

thin yellow whey and feed it to the pigs, taking frequent toll of the

sweet curd as he dipped. One day he took such heavy toll he was

completely cloyed, and it was a month of Sundays before he wanted to

taste it again.

The curd, suspended in an old table cloth, dripped for hours, and

then was packed in the big hoop, or cheese mold, and put in the

press; a kettle filled with stones hanging on the end of the lever of

the press affording the weight. The green cheese stood in the press

for weeks, and when released was dry and solid. Stored in the back

bedroom, it was not cut until seasoned, and then only when company came.

"And that's the cheese of it," was slang in John's boyhood.

CANDLE-MAKING

The boys liked to watch their mother make candles.

"Go and fetch me the rods and bars - I'm going to dip candles

this afternoon," their mother would say, and John and Eden would

bring the candle-bars and the bundle of candle-rods from the attic,

placing the bars with their ends resting on the backs of chairs, in

readiness to support the rods. These about three feet long, were

whittled by the boys out of elder wood.

The tallow, obtained from a beef they had killed, was put into the

big caldron of hot water. Twelve pieces of wicking about sixteen

inches long were hung over each rod a few inches apart, and twisted

and tied. (This left a loop at the top of each candle, which had to

be burnt off when first lighted.)

The boys made themselves useful in handing the rods to their mother,

who, after dipping the dangling wicks in the melted tallow, rested

the rods on the long bars. By the time she had dipped them all, the

first rod-full was ready for the second dipping; and so on till all

were dipped thirty or forty times. It was fun to see them grow bigger

with each tallow bath till large enough to fit the candlesticks.

Sometimes, looking critically at a rod-full, she would decide that

they needed one more dip, so in they would go again. When they were

cool enough, she would carefully straighten them, and John and Eden

would slip them off the rods, smooth the butt ends, and pack them

away from rats and mice on a shelf in the wash-house. Many a time of

a winter evening John would hear the familiar injunction, "Run

and fetch a candle, John-this is 'most burnt out."

Those dipped candles looked quite different from the symmetrical

paraffine candles we use to-day; yellowish white, and bigger at the

butt-end, they tapered to a rather small calibre at the top. Because

of this slender top, they would burn down very fast when first

lighted. The wicks, much larger than those of modern candles, were

"big as a rye-straw," and required frequent snuffing.

Farmer Burroughs used to do it quickly with thumb and finger, and

John himself got so he could snuff them deftly Without burning

himself, but his mother and the girls used the brass snuffers on the mantelpiece.

Later the farmers' wives bought tin moulds and, arranging the wicks

in them, poured the tallow in the mouldsa much quicker process, and

one resulting in candles of uniform size.

The iron candlesticks had an arrangement on the side for moving the

candle up as it burned away, and at the top was a little hook by

which they hung the candlestick to the back of a chair. It was

extravagant to have more than one candle lighted, unless there was

company. Of an evening, John would bring his book and sit close to

his mother as she sat mending and leaning toward the chairback where

the lighted candle hung. The round base of the candlestick was sharp

on the rim. They used this rim to scrape the bristles from the hogs'

backs at hog-killing time.

The boys helped with soap-making by filling the leachtub with ashes

after having put in straw through which to strain the lye. The

leach-tub was usually a hollow basswood tree which held many bushels.

It stood on a slant with the smaller end down, on a big flat stone

out by the wash-house. A groove in the stone conducted the lye to a

big cauldron. If a suitable tree could not be found, a triangular tub

was made by a carpenter -- a reversed truncated cone, held together

with a square frame.

The ashes in, they poured water through from time to time, and after

a while, out from below flowed the dark brown lye. They judged when

this was strong enough by dropping in an egg which floated only when

the lye was of the required strength.

Into the cauldron with the lye they dumped all the grease collected

since the last soap-making; all the scraps tried out from the lard

since hog-killing time-ham rinds, pork fat, and all other waste

grease-in it all went. Then, with a fire under the kettle, someone

stirred the mass with a long stick from time to time. From this there

finally resulted the brown, jelly-like, slippery soft soapthe only

soap which they had to use. A little wooden dish of it always stood

on the end of the wash-bench in the kitchen, and when the boys wanted

to scrub up, they would dip in their fingers and besmear their hands

with the glairy, strong-smelling liquid. There may have been some

kind of toilet soap in the best bedroom, but if there was, John has

no recollection of it now.

FRUIT-GATHERING

The boys and girls helped with fruit-gathering and drying. John and

his mother usually gathered the most of the berries, for, as has been

said, he was her best berry picker. He knew where the biggest berries

grew. Day after day they would go out in the hill-meadows and down in

the bark-peeling. Oh, those strawberry days amid the daisies, the

tall timothy, and the bobolinks! There was no other berry John liked

so well, it delighted so many of his senses; eye, ear, nose, and

tongue came in for their share; beautiful as a flower to look upon,

it snapped and crackled as he severed it from the stem; it smelled --

Oh, how good it smelled! and tasted! -- but there's no describing its

taste! A handful of the dead ripe berries in a bowl of bread and

milk, and the king in his parlour eating bread and honey were an

object of pity in comparison!

They went along the borders of the fields for "rozberries,"

down in the bark-peeling for blackberries, and up on Old Clump for

huckleberries. In these excursions John always brought home a good

deal besides berries, yet always had a heaping measure of them.

The girls had the dull work of looking over the berries and spreading

them on plates to be dried in the sun, or, after the advent of the

kitchen stove, in the oven. The berries had to be stirred and turned

till thoroughly dried. That was drudgery. John had the best of the bargain.

When they dried apples, Hiram, the handy one, pared them, sitting

astride the machine be had made, while the others cut and cored them,

stringing them on heavy linen thread, after which they were hung on

poles and suspended from the kitchen ceiling. Hiram also made the

knives for the machine from parts of an old scythe-blade. None of the

farmers anywhere round had as good paring-knives as Hiram's. He was

in great demand at the apple-cuts.

Our lad always had a sweet tooth, but it wasn't often catered to.

"Lockjaw," made from maple sap, and wild honey were the

lollypops that Mother Nature offered him, but there was little candy

or sweetmeats, and little canning or preserving in those days. Store

sugar was scarce and expensive (as to-day). Still, every fall Mother

Burroughs would put up a jar of pears, pound for pound, though these

were served only on special occasions.

The boys used to go across the fields in the October days to

"Aunt" Dolly's and gather a peck of pears (plus as many as

they could conveniently stow away in a certain pear-shaped receptacle

of elastic texture, which "Aunt" Dolly never saw), picking

them very carefully, for their mother wanted the stems left on.

Sometimes they went to "Aunt" Dolly's when not sent there.

At such times, they went by night, moving cautiously and quietly,

plucking the fruit speedily, regardless of stems. Such pears were

preserved in the hay-mow for future use.

One moonlight night four of the boys went over there for a raid on

the old seedling pear-tree of which "Aunt" Dolly was so

stingy. She had planted the tree herself back in seventeen hundred

and something. No wonder she was so "near" with its fruit!

"Uncle" Eli heard the boys and "calculating" that

it was "Chauncey's boys after them pears," sent his

Newfoundland dog out to sick 'em.

When Lige came bounding out, Hi and Curt "beat it," but

Wilson and John stood their ground. Wilson had a brass pistol. The

boys retreated slowly and in order. Wilson, behind with the' pistol,

backed away. When the dog came close, Whang! went the pistol in his

face. Lige fled to the house, and the boys fled home. Though a blank

charge, it served its purpose.

At another time Jane and John arranged a little visit over to

"Aunt" Dolly's, for, small as were those pears, when dead

ripe, they were sweet and juicy, and Jane and John had a hankering

after them which grew as the pears grew. Their scheme was this: Jane

was to go to the house and engage "Aunt" Dolly in the

liveliest conversation of which she was capable, while John was to

whisk around to the pear tree and occupy himself diligently for a

brief but fruitful period.

While fulfilling his part of the bargain with the utmost diligence,

likewise pockets, and stomach, wondering meanwhile what topics of

conversation were occurring to the none-too-ready Jane, behold what

John doth see -- "Aunt" Dolly, rushing around the corner of

the house, her white cap flopping indignantly, her tongue lashing

unstintingly! The fruit-gatherer, standing on the fence, with

protruding pockets, is suddenly arrested. Apparently his labours in

this line are at an end. He is speedily persuaded to come to the

ground. He is furthermore persuaded to empty his pockets of every

last pear. One by one they go reluctantly into "Aunt"

Dolly's out-held apron. Discomfited, Jane and John return across the

fields, a sorry pair (poor Jane, after all her efforts, not having

had a single taste!), while "Aunt" Dolly triumphantly

carried the gathered fruit into the house. |

|

John Burroughs On the "Giant Steps" |

THE OLD-TIME WATER SYSTEM

In John's time the water was brought down to the house from the

spring on the hillside in a primitive way, by means of pump-logs

bored out with an augur and laid in a trench under the ground, thence

conducted to the penstock-an upright hollowed-out poplar log into

which the water poured through a strainer, and from which it flowed

out of a spout into the watering-trough at the rear door. |

|

When Farmer Burroughs had to renew his pump-logs he would take the

boys with him up on the mountain and cut and haul down the

"popple" logs, after which a man from Moresville came with

his big augur to bore them. It was great fun to watch the man with

his fifteen-foot augur bore the holes. John remembers the laying of

two sets of pump-logs in his time, besides the occasional boring of

some which would decay from time to time.

PICKING GEESE

"John, you and Eden go and shut up the geese -- I'm going to

pick them after dinner," their mother would say, and such a

squawking as was heard when the boys drove them into the stable!

Sitting on a low chair in the barn, and, taking a struggling goose

from one of the boys, tucking its head under her arm, their mother

deftly and quickly plucked it on belly, sides, and back. It was a

sorry sight when plucked! Shouting derisively, the boys would

liberate it, bring her another protesting victim which, in time, they

would let out to its fellows, squawking as it went. When she plucked

the old gander, disreputable as he looked, he always returned to his

wives bragging ludicrously, though what he had to brag about, unless

that he had escaped with his life, was hard to guess.

The feathers were later made into beds and pillows. It was the custom

in those days, besides keeping up the supply for the family, to make

extra beds and pillows, from time to time, so that each boy and girl,

when married, could have a feather-bed and a pair of pillows. John's

head for many a later year rested on the feathers of those squawking

geese he had coralled for his mother to pluck.

THE BEDS OF AULD LANG SYNE

Spring beds were unknown in John's boyhood. The four-posted

cord-bedsteads, mostly of cherry (mahogany only for the well-to-do),

were strung across and criss-cross, making squares of strong cord

which supported the mattress, or straw-tick. The bed-cord was

tightened with a home-made tool fashioned for the purpose. In winter,

feather-beds were used on top of the straw-ticks. Sometimes a

corn-husk mattress was used in place of, or above, the straw.

From time to time the oat-straw had to be renewed, for, when broken,

it matted and became lumpy. It was then the boys' stunt to take up

their beds and walk with them to the stables or the pig-pen, where

henceforth the straw served as bedding in a humbler capacity. The

ticks, filled with fresh, springy straw -- oh! how luxuriously they

sank down into them at night!

Their pillows were of goose-feathers, the sheets and pillow-cases of

home-made linen, made from flax which the boys had helped gather, and

their mother had spun. The patchwork quilts, pieced by the girls and

their mother, were quilted by friends and neighbours who came to the quilting-party

from miles around. Willingly the boys brought down the

quilting-frames from the attic and set them up in the "other

room," knowing that, besides other goodies, they were pretty

sure to have white bread, new cheese, and preserved pears for supper!

The comfortables, wadded, chintz-covered affairs, sparsely tied with

bits of bright-coloured yarn, were also tied off at the quilting-bees. |

|

Over quilts and comfortables was spread the blue and white

"kiverlid" woven from the wool that grew on the sheep which

the boys had chased over the breezy hills, driven to be washed in

Hardscrabble creek, and collected in the barn to be sheared.

"As ye make your bed, so shall ye lie in it." I wonder if

sleep would not be a little sweeter and sounder on such a bed,

home-made and homegrown, than on our spring beds with glittering

brass bedsteads, hair, or felt, mattresses, ready-made sheets, rose

blankets, and the modern counterpane. But a boy's sleep is pretty

sure to be sound and sweet anyhow, whether he rest on an up-to-date

mattress or on a downy bed of Auld Lang Syne.

NEIGHBOURHOOD CHARACTERS

There was "Aunt" Debby Scudder who lived alone in a little

brown house over on the cross-roads. She kept six cows, milking and

foddering them herself, worked her own garden, and did many a job

ordinarily done by men, doing the work well, and letting neither the

grass nor the weeds grow under her busy feet.

She was a meek and pious soul, yet one Sunday

as the Burroughs family were driving by in their "pleasure

wagon," on the way to the old yellow meeting-house at

Shacksville, they were dumbfounded to see "Aunt" Debby out

by the side door, rubbing away at the wash-tub.

"Deborah Scudder! what do you mean by washing on Sunday?"

Throwing up her hands dripping with suds, "Aunt" Debby

cried aghast, "Sunday! is to-day Sunday?" When convinced

that it was, without another word she dried her hands on her apron,

left her tubs without a glance back, and hurried into the house,

presumably to wrestle with the Lord for her offence in having broken

His Commandment. Certain it is she did not go to hear Elder Hewitt

that day.

The boys went to church only occasionally, walking across lots (which

compensated some), while their parents and the girls rode in the

pleasure wagon. Groaning in spirit to exchange the sunlit fields for

that ugly old church, they seated themselves in the gallery where

they could look down upon the worshippers (the men on one side, the

women on the other), managing, somehow, to live through the two long

hours that Elder Hewitt spent in his chaotic discourse. " He was

a solemn old raven, but a man of solid worth and sterling

qualities," said the man who sat so unwillingly under his

preaching as a lad. He never got anywhere. There was no

reasoning-just a lot of texts strung together, with occasional

emotional outbursts. These outbursts were oases in the solemn,

lugubrious delivery that at last came to an end and let the sufferers

escape into the sunshine again. |

|

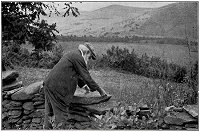

John Burroughs scattering corn for the chipmunks at Woodchuck Lodge

|

When the old elder had his fling at the unregenerate Armenians, as

the Methodists were then called, the boys liked it immensely, for

then there was some "git up and git" to what he said. How

he used to rollout those magic words, "foreordination," and

"predestination "-words which meant that the chosen few,

the Old School Baptists, had their names written forever in the

Lamb's Book of Life! Their " calling and election " were

sure. That sect, to which John's parents belonged, believed that one

was "saved by grace," not by "works"; that there

was no such a thing as "free salvation," as the Armenians

advocated, but that one's name had to be on the roll-call from all

eternity, if one was to be saved. |

|

The Yearly Meetings were welcome breaks in the usual solemn Sunday

observances, the human element being more in evidence then. The

families would come from far and near; the sheds and the church-yard,

too, would be filled with wagons and horses. Each family brought

great baskets of provisions. Although the forenoon and afternoon

sessions were long, drowsy affairs, the noon hour, with the decorous

picnic on the grass, atoned for a multitude of texts. Then the men

stood or sat around on the ground, discussing the weather and the

crops. The women bustled about, spreading out the victuals, and

gossipping about their weaving and dyeing, their patchwork, and their

carpet-rags. The hungry boys hovered near, eyeing the good things

which made their mouths water, and longing for the time when, the

long grace ended, they could fall to and dispose of the things

predestined to be devoured. After that the men lounged about and

smoked, the women walked reverently among the graves of kindred and

neighbours, speaking in low tones, sometimes secretly wiping away a

tear, pulling a weed here and there, and reading over the lines on

the headstones. Then it was that the boys quietly stole away to

Stratton Falls, their absence from the afternoon session being

tacitly agreed upon. Once there, forgetting all about the weighty

doctrines Elder Hewitt was so earnestly expounding in the dismal

church, they gave themselves up to the good times it was foreordained

from the beginning that boys in all ages shall enjoy.

Sometimes instead of going to church at Shacksville the Burroughs

family rode over to Brag Hollow to hear Elder Jim Meade hold forth.

John's father was sometimes so carried away by the eloquence of this

simple, fine old man, that he knew not whether he was in the body or

out of the body. The Elder worked his little farm on weekdays and

preached on Sundays. Coming into the schoolhouse barefooted and,

standing up among his neighbours, he would open his mouth and trust

to the Lord to fill it, while his hearers sat awed by his homely eloquence.

Sylvester Preston, the carpenter who built the wagonhouse for John's

father, was quite a wag and had his little joke at the expense of

Farmer Burroughs:

"Chauncey, it's the rule for a carpenter to take home twenty

nails with him every night, and I shall have to follow the rule,"

he said, as the first day's work was drawing to a close.

"By Phagus!" ejaculated Farmer Burroughs, as he thought of

how much those wrought nails cost, and what an item it would be

before 'Vester got the wagon-house done. But he added resignedly,

"Well, if that's the rule, 'Vester, I suppose you'll have

to," and he went about with a worried look, helplessly pondering

the injustice of it. When night came he stood there ruefully,

expecting to see Sylvester take his twenty nails. Then, with a loud

guffaw, the carpenter made him understand that the nails he was to

carry home were those which Mother Nature had forged for him, and

that he would bring the same ones back with him every morning. |

Footnotes:

- "pleasure wagon": A three-seated wagon, made by

hand, by Nell Dart, and taken to Enderlin's blacksmith shop in the

Hollow to be "Ironed." It cost seventy-five or eighty

dollars, a good deal of money then, and was the source of pardonable

pride to any farmer thrifty enough to own one. (Return)

|

|

|

|