|

The Hermit of Slabsides, West Park on the Hudson

John Burroughs in woodchuck coat

John Burroughs providing for the chipmunks

Roxbury, NY

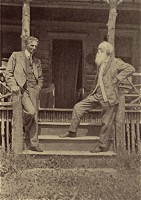

Henry Ford and John Burroughs at Woodchuck Lodge

Memorial tablet to John Burroughs on Boyhood

Rock, Roxbury, NY |

(Note: Earlier versions of this essay first saw

print in March/April 1982 edition of THE CONSERVATIONIST March/April

and in the Summer 2001 edition of the Mountain Top Historical

Society's HEMLOCK.)

Early in 1873, John Burroughs purchased a

nine-acre farm on the banks of the Hudson River at West Park

(Esopus), NY, ninety miles above Manhattan. At the time he was

thirty-six years old and had barely begun to write nature essays. The

farm, which he named Riverby ("by-the-river," but

pronounced "riverbee") was more expensive than he would

have liked, but the setting of the place was one that appealed. In

addition, the farm lay within a day's ride of his family home - the

dairy farm on which he'd been raised - at Roxbury, in the Catskills.

Life at Riverby proved ideal for Burroughs. For

nine years he had worked a desk-job at the Federal Treasury in

Washington, DC. Now he wanted a way to make a living that would leave

him leisure in which to also make books. Tending to his fields,

Burroughs could at the same time contemplate the wide river spread

out before him. A short walk brought him to a hemlock woods a mile or

two inland. Black Creek, a small stream he would come to love, ran

through the trees.

Unlike his first writings, Burroughs's

subsequent work of over twenty volumes would need not be written at a

desk facing the iron wall of a vault in the Treasury Department. Also

unlike his first essays, all his best outdoor writing would

henceforth be infused with images of nature as found on familiar

terrain - the Hudson River Valley and Burroughs's adjacent natal

region of the Catskills. Like Thoreau, who said he had "travelled

widely in Concord," Burroughs would in future always seem

content to travel widely in Ulster and Delaware Counties.

"Nature comes home to one most when he is

at home," he wrote in 1886, "the stranger and traveler

finds her a stranger and traveler also. One's own landscape comes in

time to be a sort of outlying part of himself; he has sowed himself

broadcast upon it, and it reflects his own moods and feelings; he is

sensitive to the verge of the horizon: cut those trees, he bleeds;

mar those hills, he suffers."

Interestingly, although the Hudson Valley and

the Catskills provided the main fodder for Burroughs's nature notes,

the Hudson River itself - which flows through one, by the other, and

does so much to define both - never dominated his pen. In fact, of

all the essays Burroughs ever wrote, only one - "A River

View" in the 1886 volume SIGNS AND SEASONS - dealt with the

Hudson at any length. More often Burroughs based his essays in the

world of the hemlock woods inland from the river, on the banks of

Black Creek, or in the Catskills forests of his youth, to which he

always returned.

Why did Burroughs, in his published writings,

shun the beautiful river on which he had chosen, at the age of

thirty-six, to build his home?

In the book SPECIMEN DAYS, parts of which were

written while visiting at Riverby, Burroughs's friend Walt Whitman

described the scene of the Hudson as glimpsed from the Burroughs

farm. Whitman's pen especially captured the magic of the calm river

in evening: "The river at night has its special

character-beauties. The shad-fishermen go forth in their boats and

pay out their nets - one sitting forward, rowing, and one standing up

aft dropping it properly - marking the line with little floats

bearing candles, conveying, as they glide over the water, an

indescribable sentiment and doubled brightness ... the sloops' and

schooners' shadowy forms, like phantoms, white, silent, indefinite,

out there." Whitman describes an eminently attractive scene: one

that beckoned hourly to Burroughs as he worked in his fields.

Nevertheless, throughout the journals of John Burroughs, one finds

nary a trace of the river.

In one rare moment of homage to Father Hudson

- this dated 10 October 1883 - Burroughs wrote to chronicle: "

... our matchless October day -- the ripest best fruit of the weather

system of our clime ... The early frosts are over, and the fall heats

are passed, and the days is like a full-orbed mellow apple just clinging

to the bough. The great moist shadows of the opposite shore I see through

the tender medium of sunlit haze ... A sloop goes drifting by, part

of her sail a blue shadow. I can hear the ripples of the water about

her bow. The day is retrospective, and seems full of tender memories."

The image, observed "through the tender

medium of sunlit haze," sounds almost like a scene from a work

of the Hudson River School. As described by Carl Carmer, the chief aim

of such Hudson River artists as Asher Durrand and Thomas Cole was to

depict, as near to reality as possible, the Creator's greatest natural

handiworks. The selection of sublime subjects made these paintings appear

romantic in sentiment and majestic in scope despite the rule of most

Hudson River artists that natural beauty be recreated exactly as it

was, with no attempt by mortal hands to improve upon the artistry of

God. The point was to make whoever viewed the work of art feel, as Carmer

has written, "awed and humble in the presence of divine sublimity."

|

|

Offering some of the most sweeping and awe-inspiring

vistas in the world, the Hudson was well suited to be the home of such

a school of painting. What attracted the Hudson River painters, however,

in turn repelled John Burroughs.

Unlike the Hudson River painters, John Burroughs's

artistic aim was not to make his readers feel diminished by, or in anyway

set apart from, the whole of nature. Quite the contrary. As he wrote

in the 1877 volume BIRDS AND POETS, "... when I go to the woods

or fields, or ascend to the hilltop, I do not seem to be gazing upon

beauty at all, but to be breathing it like the air. I am not dazzled

or astonished; I am in no hurry lest it be gone. I would not have ...

the banks trimmed, or the ground painted. What I enjoy is commensurate

with the earth and sky itself. It clings to the rocks and trees; it

is kindred to the roughness and savagery; it rises from every tangle

and chasm; it perches on the dry oak stubs with the hawks and buzzards

... I am not a spectator of, but a participator in it. It is not an

adornment; its roots strike to the centre of the earth."

Burroughs sought, and found, the universal in

the local; he likewise wished to discover the cosmic as revealed by

the most simple and understated aspects of the natural world. In the

final analysis, the Hudson as natural phenomena impressed him no more

than did the miracle of a hummingbird's nest. In other words, what

Burroughs wanted from nature was something more complex and

interesting than the mere picturesque. Nature's grandest

demonstrations - the panoramas of the Hudson or the Grand Canyon, the

geysers of the American West, and the glaciers of Alaska - never

impressed him more favorably than did the Catskills trout streams he

had frequented so earnestly in both his youth and maturity. Indeed,

he much preferred the latter.

Thus, when Burroughs eventually came to write

about the Hudson in "A River View," he used the opening

paragraphs to explain exactly why the river did not attract him.

"A small river or stream flowing by one's door," he wrote,

"has many attractions over a large body of water like the

Hudson. One can make a companion of it, he can walk with it and sit

with it, or lounge on its banks, and feel that it is all his own. It

becomes something private and special to him. You cannot have the

same kind of attachment and sympathy with a big river; it does not

flow through the affections like a lesser stream. The Hudson is a

long arm of the sea and has something of the sea's austerity and

grandeur. I think one might spend a lifetime on its banks without

feeling any sense of ownership in it, or become at all intimate with

it; it keeps one at arm's length."

Burroughs returned to this theme in 1895 when

explaining why he'd built a small cabin retreat - Slabsides - a few

miles to the west of Riverby. "Friends have asked me," he

wrote, "why I turned my back upon the Hudson and retreated to

the wilderness ... To a countryman like myself, not born to a great

river or an extensive water-view, these things, I think, grow

wearisome after a time. He becomes surfeited with a beauty that is

alien to him. He longs for something more homely, private, and

secluded. Scenery may be too fine or too grand and imposing for one's

daily or hourly view. It tires after a while. It demands a mood that

comes to you only at intervals. Hence it is never wise to build your

house on the most ambitious spot in the landscape. Rather seek out a

more humble and secluded nook or corner, which you can warm with your

domestic and home instincts and affections. In some things the half

is often more satisfying than the whole. A glimpse of the Hudson

River between hills or through openings in the trees wears better

with me than a long expanse of it constantly spread out before me."

Burroughs retreated even further from the

Hudson when, as of 1910, he took to spending his summers in a cottage

- Woodchuck Lodge - on his boyhood farm in Roxbury. Here he came full

circle, returning to the countryside of his youth for what would

prove to be the last ten summers of his life. He relished the

landscape here, and did not seem to miss the Hudson at all. Writing

in an essay entitled "The Circuit of the Summer Hills," he

told his readers that at Roxbury: "The peace of the hills is

about me and upon me; the leisure of the summer clouds, whose shadows

I see slowly drifting across the face of the landscape, is mine. The

dissonance and the turbulence and the stench of cities - how far off

they seem! The noise and dust, and the acrimony of politics - how

completely the hum of the honey-bee, and the twitter of the swallows

blot them out! In the circuit of the hills the days take form and

character ... The deep, cradle-like valleys, and the long flowing

mountain-lines, make a fit receptacle for the day's beauty ... The

valleys are vast blue urns that hold a generous portion of lucid hours."

The view of his old age was the view of his

childhood. It stopped at the brow of his hill. And that was far

enough: the half always more satisfying than the whole.

=====

EDWARD J. RENEHAN JR.

erenehan@yahoo.com

http://edrenehan.com/

Back to the John Burroughs Page

|