THE EARLY HISTORY OF THE

BALTIMORE & OHIO R.R.

Engineering News—July 14, 1892

Address of President Mendes Cohen at the Annual Convention

of the American Society of Civil Engineers

April 1, 1832, the line was opened to the Potomac River at

the Point of Rocks, a distance of 70 miles from Baltimore, and

was regularly worked throughout by horse power. It had been contemplated

to effect with inclined planes the crossing of Parr's Ridge, the

summit of which was 800 ft. above tide and the eastern foot of

which was reached at about 40 miles from Baltimore. The placing

of the machinery for working the planes was, however, deferred

from year to year and the traffic carried across the ridge by

horse power, until the development of the engines powerful enough

led to their being tested on the heavy grade of the Inclined planes.

At the very outset work along the Potomac was stopped by litigation

resulting In favor of the Canal Company; a compromise was sought

and finally effected in the spring of 1833. The immediate difficulty

was the passage of the several spurs of the Blue Ridge, which

are cleft by the river with bold and rocky slopes, are first encountered

by the road in the Catoctin Mountain, at the Point of Rocks, and

continue at intervals for 12 miles to Harper's Ferry. The compromise

arranged need not be considered here. It was onerous enough, but

could not be avoided, and under it the work was completed to a

point opposite Harper's Ferry by December, 1834. During these

years of obstruction, authority had been obtained to construct

a branch road to Washington, and in 1831, Mr. B. H. Latrobe was

appointed an assistant and assigned to the reconnaissance. This

was followed up without delay by a more definite and careful examination.

Mr. Knight takes a most comprehensive view of what he says must

become a great national highway. He urges that no grades exceeding

20 ft. per mile, nor any curve of less radius than 1,500 ft.,

or in extreme cases 1,000 ft., be tolerated if avoidable at any

reasonable expense, so that light locomotives may make the run

regularly In two hours, and indicates the possibility of a "message

being made to pass the whole distance from Washington to Baltimore

in one hour."

The surveys were continued with great minuteness so that, as

the President expresses it, "the route finally adopted should

leave no better one available to a rival corporation."

In July, 1833, Mr. Knight submits his report and analyses of

twelve alternative lines with a degree of elaboration and care

that I venture to say has rarely been equaled. The line recommended

by him was at once placed under contract and under Mr. B. H. Latrobe,

as the engineer in charge, was completed and opened Aug. 25, 1835.

At its point of divergence from the main stem, seven miles from

Baltimore, it crosses the Patapsco by a masonry viaduct of eight

arches, each of 58 ft. chord, some 70 ft. in height above the

water and of a total length of 707 ft. This was designed by Mr.

Latrobe and stands to-day a monument to his taste and professional

skill. The superstructure of the branch road was intended to be

a great improvement on the various forms used thus far on the

main stem. It consisted of longitudinal sills 6 ins. square and

from 12 to 40 ft. in length, laid in trenches so cut for their

reception that the upper surface of the sills will be from two

to five Inches below the graded surface of the roadbed. On this

were laid cross ties 4 ft. from center to center and cut out to

receive stringer pieces of yellow pine 6 ins. square on which

were laid the first heavy T rails

used on the road. This rail weighed 40 lbs. per yd., as proposed

by the Chief Engineer and modified in the shape of its face or

surface by Mr. Ross Winans.

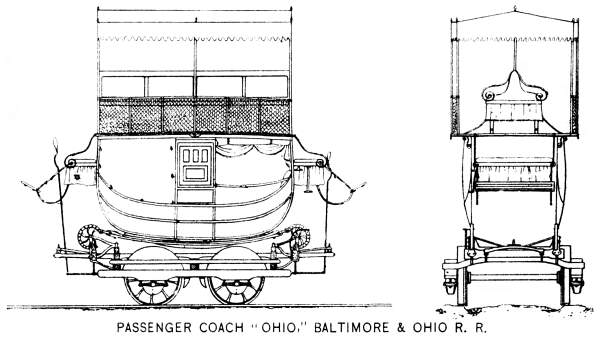

I must now

say something of the progress made in coaches, cars and car wheels.

The coaches were at the outstart made about as comfortable as

the stage coach of the day, and were built on much the same pattern;

but, of course with cast iron wheels. The "Ohio," of

which I am able to show you a lithograph, was all improvement

on these which had preceded it. You will see that it is provided

with Mr. Winans' anti-friction boxes. So long as horse-power alone

was used nothing better was required. As soon, however, as the

locomotive appeared upon the road, there came with it the necessity

for modification in the carriages. The wheels, at first light

to save weight, were made heavier, to give needed strength with

increased speed. Mr. Knight improved the shape of the tread and

flange, while John Edgar and Ross Winans developed its chilled

features and Phineas Davis further improved and perfected the

whole by altering the disposition of the metal in the tread and

angle of the flange and by introducing within the wheel a wrought

iron ring of five-eighths or ¾ in. round iron which, not

only perfected the chill, but increased the strength of the wheel.

So satisfied was Mr. Knight with the result that he observes at

quite an early stage "the cast iron wheel has probably attained

the utmost perfection of which it is capable." Thousands

of these wheels were made at Mr. Winans' shops, not only for use

in various parts of this country, but for some of the German and

Swiss roads, which used them extensively up to 1851. Mr. Knight,

in his report for 1836, states that the chilled wheels had run

30,300 miles and more at the high speed used on the Washington

branch without the failure of a single wheel, and he had every

reason to believe that 50,000 miles might be accomplished by them. I must now

say something of the progress made in coaches, cars and car wheels.

The coaches were at the outstart made about as comfortable as

the stage coach of the day, and were built on much the same pattern;

but, of course with cast iron wheels. The "Ohio," of

which I am able to show you a lithograph, was all improvement

on these which had preceded it. You will see that it is provided

with Mr. Winans' anti-friction boxes. So long as horse-power alone

was used nothing better was required. As soon, however, as the

locomotive appeared upon the road, there came with it the necessity

for modification in the carriages. The wheels, at first light

to save weight, were made heavier, to give needed strength with

increased speed. Mr. Knight improved the shape of the tread and

flange, while John Edgar and Ross Winans developed its chilled

features and Phineas Davis further improved and perfected the

whole by altering the disposition of the metal in the tread and

angle of the flange and by introducing within the wheel a wrought

iron ring of five-eighths or ¾ in. round iron which, not

only perfected the chill, but increased the strength of the wheel.

So satisfied was Mr. Knight with the result that he observes at

quite an early stage "the cast iron wheel has probably attained

the utmost perfection of which it is capable." Thousands

of these wheels were made at Mr. Winans' shops, not only for use

in various parts of this country, but for some of the German and

Swiss roads, which used them extensively up to 1851. Mr. Knight,

in his report for 1836, states that the chilled wheels had run

30,300 miles and more at the high speed used on the Washington

branch without the failure of a single wheel, and he had every

reason to believe that 50,000 miles might be accomplished by them.

The increase of speed due to the use of steam made greater

steadiness desirable in the coach than was possible in the four-wheeled

car. The long stringers and sills for the track, some of them

as long as 40 ft., had been heretofore carried over the finished

road on two of the ordinary four-wheel platform cars coupled by

a long pole. On the platform of each of these cars there rested

transversely a bolster with a vertical pin, or king bolt, passing

through its middle point and so connected to the platform of the

car as to permit the bolster to swivel freely. On these bolsters

of the two connected platform cars and stretching from one to

the other, the track timbers referred to were laid. Vertical stakes

secured to the ends of the bolsters prevented the timber from

rolling off. This contrivance, a very familiar and natural one,

and not even then used for the first time, answered its purpose

perfectly and from its steadiness of motion suggested to the active

mind of Ross Winans, the carrying of passengers on a car constructed

on the same principle. His experiments soon followed and in the

annual report of Oct. 1, 1833, the Superintendent of Machinery

notes that he is building three car bodies to form one coach on

eight wheels to carry 60 passengers. This was the birth of the

eightwheel car which was patented by Mr. Winans and, though the

courts after long litigation decided adversely to his claim on

the ground, I believe, of prior use, as in the case of the timber

car and similar one for transporting large blocks of granite at

Quincy, Mass., yet I have always believed that to Ross Winans

we are Indebted for this great improvement. Very soon thereafter

eight-wheel cars were used throughout the line for both passenger

and freight traffic and special cars were provided for baggage,

which had theretofore been carried on top of the coaches.

I have stated

that the road was opened to Harper's Ferry in December, 1834.

The portion of the line crossing Parr's Ridge, located for inclined

planes, with stationary engines at a maximum grade of 270 ft.

per mile, was still worked by horses, as were also the 12 miles

between Point of Rocks and Harper's Ferry. The latter section

was so worked on account of the opposition of the canal company

to the use of locomotives because they frightened the canal horses.

Trials of the new Davis engine, having been made on the planes

of Parr's Ridge, and the ability of the engine to overcome even

a grade of 270 ft. having been fully demonstrated, the road across

the bridge was re-located to adapt it for locomotive power. This

was done with grades of about 80 ft. per mile, increasing the

distance less than one mile, and was put in operation in June,

1839. A pecuniary consideration to the canal company having meanwhile

steadied the nerves of their horses, the whole line as far as

completed was in operation with locomotives. I have stated

that the road was opened to Harper's Ferry in December, 1834.

The portion of the line crossing Parr's Ridge, located for inclined

planes, with stationary engines at a maximum grade of 270 ft.

per mile, was still worked by horses, as were also the 12 miles

between Point of Rocks and Harper's Ferry. The latter section

was so worked on account of the opposition of the canal company

to the use of locomotives because they frightened the canal horses.

Trials of the new Davis engine, having been made on the planes

of Parr's Ridge, and the ability of the engine to overcome even

a grade of 270 ft. having been fully demonstrated, the road across

the bridge was re-located to adapt it for locomotive power. This

was done with grades of about 80 ft. per mile, increasing the

distance less than one mile, and was put in operation in June,

1839. A pecuniary consideration to the canal company having meanwhile

steadied the nerves of their horses, the whole line as far as

completed was in operation with locomotives.

The increasing demand for these machines was partly met by

replacing the engines at work on the Washington branch by others

built by Mr. William Norris, of Philadelphia, having horizontal

boilers and one pair of driving wheels of four feet diameter,

with a truck in usual form, cylinder of 10½ ins. in diameter

and 18-ins. stroke and weighing nine tons with 5½ tons

on the drivers. It was a form of engine much better adapted to

the fast passenger service of that line, and in its day a most

efficient machine. These engines used wood fuel and were followed

by others on the same general plan, using the same fuel, which

was found less costly than the anthracite coal supplied to the

Davis engines.

The crossing of the Potomac at Harper's Ferry was effected

by a timber bridge, designed by Mr. B. H. Latrobe and built by

Wernwag. It was a noted structure in its time, being modeled somewhat

upon the plan of a celebrated bridge over the Rhine at Schaafhausen.

A peculiarity of the line at this point necessitated a bifurcation

of the bridge at its western end, forming two branches of a Y, the one arm connecting by a single

span to the south with the Winchester & Potomac R. R., then

just completed to meet it; the other by two spans to the west,

being the prolongation of the main stem of the railroad.

This arrangement, involving the use of switches midway of the

bridge, was necessarily somewhat complicated, but it has been

continued to this day, although the rapidly increasing weight

of the locomotives and trains caused the replacing of the timber

bridge at a later date, 1852, by an iron truss, patented by Mr.

Wendell Bollman, the details of which were arranged by Mr. J.

H. Tegmeyer and which has been claimed as the first iron truss

railroad bridge.

The extension

of the line from Harper's Ferry westward to Cumberland, a distance

of 96 miles, was now being pressed forward with his characteristic

energy by Mr. Latrobe, the engineer of location and construction,

and was opened to Cumberland in November, 1842. The engineering

features do not call for special comment here, beyond reference

to the track superstructure, which still adhered to the subsill.

It consisted of a wooden under-sill and stringer piece with cross

ties and blocks between them, the whole fastened by wooden plus.

The iron rail was of the bridge form, weighing 51 lbs. per yd.,

with cast iron chairs at the ends and in the middle of the bars,

which were held firmly down to the stringer piece by screw bolts

at the ends and hook-headed spikes at intermediate distances.

The whole rested on a bed of broken stone one foot in depth. The extension

of the line from Harper's Ferry westward to Cumberland, a distance

of 96 miles, was now being pressed forward with his characteristic

energy by Mr. Latrobe, the engineer of location and construction,

and was opened to Cumberland in November, 1842. The engineering

features do not call for special comment here, beyond reference

to the track superstructure, which still adhered to the subsill.

It consisted of a wooden under-sill and stringer piece with cross

ties and blocks between them, the whole fastened by wooden plus.

The iron rail was of the bridge form, weighing 51 lbs. per yd.,

with cast iron chairs at the ends and in the middle of the bars,

which were held firmly down to the stringer piece by screw bolts

at the ends and hook-headed spikes at intermediate distances.

The whole rested on a bed of broken stone one foot in depth.

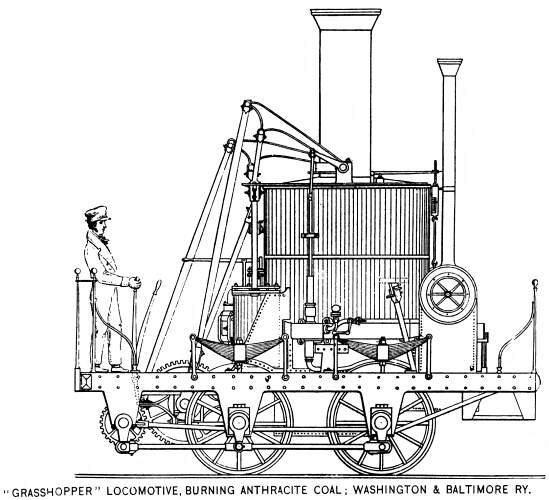

A marked stage in the development of the engines for this extension

must now be noticed. In 1836 Ross Winans constructed two engines

for the road with the Cooper vertical boiler and with the cylinders

placed horizontally at the rear end of the frames and connecting

by the spur wheel and pinion through the independent shaft to

four driving wheels, as in the "Grasshopper" engines.

This arrangement enabled the boiler to be depressed, and lowered

the center of gravity of the whole machine some 12 ins., thereby

giving greater stability at high velocity. This plan was further

developed in 1842, in seven engines, built for the. Western R.

R. of Massachusetts, which had eight drivers instead of four.

These were powerful machines, but were not a success. They were

entirely unsuited to the use of wood, and as anthracite could

not be furnished on that line at any reasonable price, the engines

were soon laid aside. On reaching Cumberland the Baltimore &

Ohio tapped for the first time the bituminous coal region and

a locomotive was wanted to burn that fuel. Mr. Winans, to meet

this demand, designed all engine with horizontal boiler and horizontal

cylinders of 16 x 22 ins., connecting with eight driving wheels

33 ins. in diameter through a spur wheel and pinion, as heretofore,

and weighing 23½ tons. Of these engines, 12 were placed

in service between 1844 and 1846, and were a great advance upon

anything which had preceded them. They burned bituminous coal

and handled the coal trade in its incipiency. They led the way

in the development of the coal burning engine, the next step in

which was the building in 1847 by Mr. Winans of four engines for

the Philadelphia & Reading R. R. with horizontal boilers,

horizontal cylinders, and eight driving wheels of 46 ins. diameter,

the use of spur gearing being dispensed with. I mention these

engines, for they have no equivalent on the Baltimore & Ohio

R. R., and yet mark the stage to the next machine known as the

"Camel." The first of this class of engines was placed

on the road in 1848 in response to specifications prepared by

Mr. Latrobe and limiting the weight to 22 tons. It had 17-in.

cylinders of 22-in. stroke placed horizontally and eight 43-in.

drivers; the firebox was larger and wider than ever before. In

distributing the weight of this engine on its four pairs of driving

wheels, it became necessary to remove the large dome from over

the firebox to a point well forward of the middle of the boiler,

where also the throttle valve and engine man were placed. This

humped feature suggested the name "Camel," which was

given to the first engine of this form, and the name has since

adhered to the type. These engines were developed in the next

few years by increase in size of boiler, firebox and cylinders,

which latter were 19 x 22 ins. with a total weight of engine of

28 tons, They were most efficient and enabled the heavy grades

of the new road west of Cumberland to be worked successfully.

In fact they were designed for these grades, and there was no

other engine then available for the purpose. This engine has been

further developed and improved upon since, largely in the shops

of the Philadelphia & Reading R. R., to which road many of

them were supplied, where its crudities have been removed and

its deficencies supplied by the skill of the several engineers

of machinery of that great corporation, notably by the late James

Milholland and by Mr. J. E. Wootten; but many of its characteristics

and important features can readily be traced—the horizontal

cylinders, the large and wide firebox, the flat connecting and

side rods; the latter arranged with fixed bushings incapable of

adjustment, a feature much reviled at the time, but now recognized

and adopted by the best builders.

The progress of the road beyond Cumberland was delayed for

five or six years by many and peculiar causes. While the original

charters granted by Maryland and Virginia were perpetual, yet

there were limitations as to time of completion which were already

exceeded and which now operated to require further legislation,

while a limitation in the Pennsylvania charter operated to annul

it altogether.

Maryland had a very large amount of money invested in the canal,

which had not yet reached Cumberland, where it now rests, and

still cherished the hope of its further extension, so that the

railroad location must still be subservient thereto.

Virginia endeavored to couple with her grants of extended time

onerous stipulations limiting the terminal point to Wheeling.

The railroad company would have preferred to locate its line

to a more southern point on the Ohio, preferably to Parkersburg,

at the mouth of the Kanawha, and was not insensible to the advantages

of a terminus at Pittsburg, but was evidently averse to Wheeling.

The well known diplomatic skill of President Louis McLane had

full scope in reconciling the difficulties, and with some measure

of success, for though the act of Virginia of March, 1847, stipulated

Wheeling as the terminus, yet the conditions were less onerous

than certain earlier acts, under which the company declined to

proceed.

It contained a section which seems to have been designed to

facilitate connection with a branch to Parkersburg. This was so

promptly availed of that the North Western Virginia R. R., now

the Parkersburg Branch R. R., was well under way before the road

was opened to Wheeling, and was completed a few years thereafter.

The definitive location of the whole line from Cumberland west

was now pushed forward by numerous parties.

At the west end three alternative lines of approach to the

Ohio presented themselves, after avoiding the southwest corner

of Pennsylvania, distant from Wheeling some 40 to 50 miles.

The first reached the Ohio at the mouth of Fish Creek, the

most southern point permitted by the act of 1847, and then followed

the river 25 miles to Wheeling.

The next touched the river at the mouth of Grave Creek, 12

miles below Wheeling.

The third, via Wheeling Creek, only reached the river at the

city of Wheeling.

The first, although the longer, had light grades and no heavy

work, and was the choice of Mr. Latrobe.

The second and third crossed several divides involving much

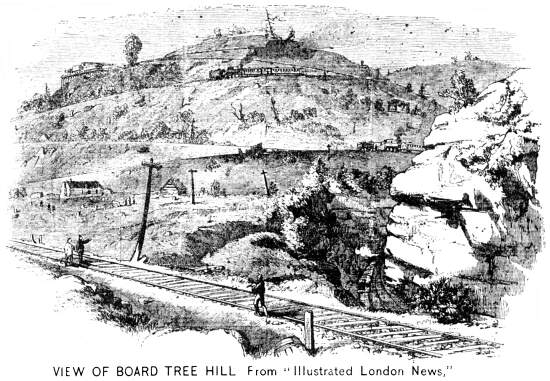

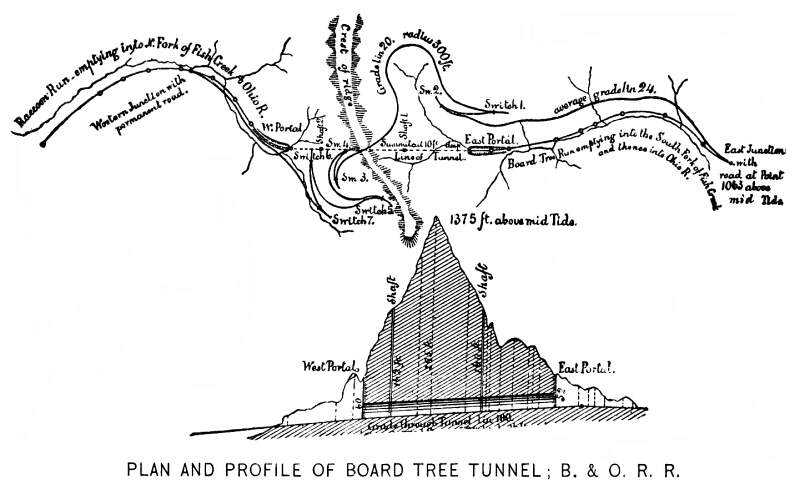

heavy work, each of the two, including Board Tree Tunnel, of 2,300

ft. with 80 ft. grades on either side.

Wheeling, fearing an attempt to deprive her of the benefits

of the actual terminus, protested against the adoption of the

Fish Creek line as contrary to the spirit of the act of 1847 and

a subsequent agreement between the city and the company. She called

to her aid Jonathan Knight and Charles Ellet, Jr., as engineer

experts.

Mr. Knight had resigned from the Baltimore & Ohio R. R.

and had been succeeded by Mr. Latrobe in 1842, about the time

of the completion of the road to Cumberland, and brought all the

knowledge and skill acquired. In the company's service during

his 15 years' connection with it to bear in opposition to its

plans and to the views of its Chief Engineer, his former assistant.

The situation may well have been embarrassing to Mr. Latrobe,

whose notions of professional ethics were, I take it, of a different

order.

It will be too long a story to enter here into the details

of the controversy. It was skillfully managed on both sides. Reams

of paper were filled with the calculations and discussions of

the engineers and with the arguments of counsel, amongst whom

were Daniel Webster, Reverdy Johnson and J. H. B Latrobe.

The matter was finally adjusted by arbitration in the autumn

of 1850, resulting in the adoption of the Grave Creek line, having

caused a further delay of three years.

The question of location having been settled, the construction

of the 200 miles from Cumberland to Wheeling was pressed at all

points with energy by able assistants, Wm. H. Small, George Hoffman,

Thomas Rowles, James L. Randolph, George McLeod, Charles P. Manning,

Benjamin D. Frost, Alfred F. Sears and Albert Fink, the latter

a Past President of the Society, are names most of which are familiar

to you.

The track from Cumberland westward was laid throughout with 60-lb.

rails on cross ties with a wrought iron H

or lip chairs of boiler plate. The latter, though better than

anything which preceded it, was very unreliable. The graded road

was ballasted ahead of the track with broken stone, sand or gravel,

as might be obtainable. The track was not yet perfect, but a great

step in advance was made when there was no longer a subsill to

churn away in the mud beneath a real or pretended ballast.

Mr. Latrobe's adoption of the 116-ft. grades in crossing the

mountains was deemed bold and hazardous, but he had been trained

in a school which was self-reliant. He made his calculations of

what he required and what he felt sure could be accomplished,

and found in Ross Winans the man who recognized the occasion and

undertook the task of designing an engine that should perform

the work. Well do I remember accompanying Mr. Winans on his first

test of the new engine on the grade for which it was designed.

The occasion was the opening of the new road in July, 1851, to

Piedmont station, 28 miles west of Cumberland. Here begins the

116-ft. grade, which continues for 17 miles to the top of the

Alleghany Mountains. The tracklaying force was busily engaged

some three or four miles beyond, and this short distance was all

that was available to see what the engine could do. As a test

of its fall power it did not amount to much, but there were attached

to the engine, in addition to the passenger cars of the excursionists,

a number of carloads of iron rails, all that were available, and

with these the engine started at the foot of the grade and made

its run at the rate of 10 or 12 miles per hour with a large surplus

of steam, which was cut off at half stroke. On arriving at the

end of the track with steam blowing off, there was much congratulation.

It was realized that the question of ability to work this grade,

of which great doubt had been expressed, was clearly demonstrated

with a large reserve of power in the engine and from that time

forward no more was said of impossibilities.

In the following winter and spring the track was carried to

and across the slopes of Cheat River. Here the deep ravines of

Tray Run and Buckeye Hollow were crossed on grades of about 105

ft. to the mile, at an elevation of some 160 ft. above the bed

of the ravine by trestle work, soon replaced by permanent structures,

the detail of which was executed by our Past President, Albert

Fink then assistant of Mr. Latrobe.

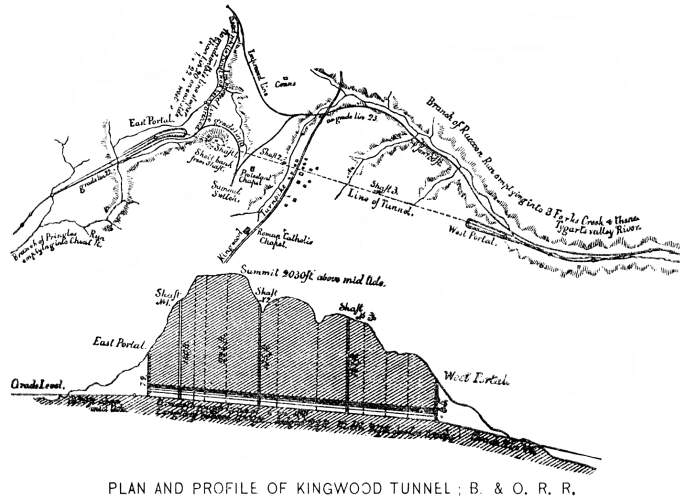

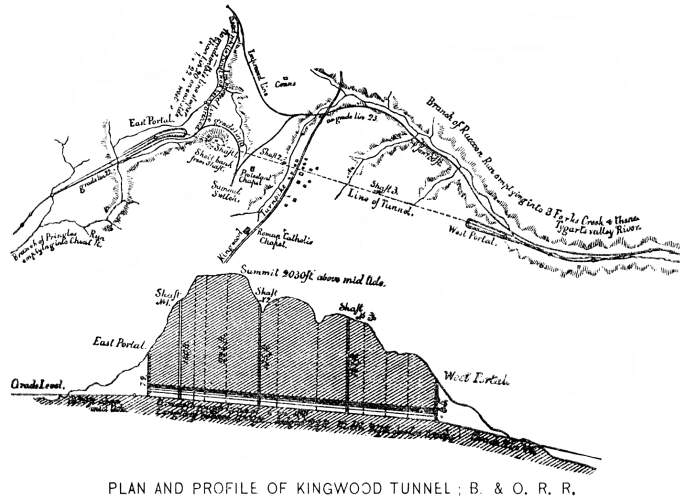

The next great feature was Kingwood tunnel of 4,100 ft. in

length. This work not being ready in time to pass the track layers

through without much delay, Mr. Latrobe determined to grade a

track over the tunnel and passing the iron over it, to continue

the work of tracklaying beyond. The maximum grade involved in

this work was 10%, which, though intended for horse power, was

worked by the "Camel" engine, which pushed over it one

car of rails without any serious difficulty. At a later period,

after the opening of the road, when the arching of the tunnel

was in progress, this temporary line was revised with a maximum

grade of 5% and the whole traffic of the road was carried over

it for some months. The crossing of this tunnel effected, the

progress of the road lay on easier lines for some 80 miles. The

Monongahela River was crossed by a bridge of three spans of 200

ft. each, The masonry of the piers and the abutments of this bridge

were intrusted to our late member, Mr. James L. Randolph, who

was the division engineer the superstructure being designed by

Mr. Fink. At Broad Tree Tunnel, about 164 miles west of Cumberland,

was encountered another temporary delay by reason of the failure

or inefficiency of the contractors. Here Mr. Latrobe again determined

to avail of a temporary crossing over the top of the hill. This

time the maximum gradient was 6%. The crossing was effected by

a series of zig-zags, or switchbacks, two on one side of the hill

and five on the other. The topography was such that there were

two curves on the line of 180 degrees and more of continuous curvature

in one direction; the radius was 300 ft. Mr. Latrobe has himself

so well described this crossing I will not repeat it here at length.

This temporary road was most successfully worked for some five

or six months. Beyond this point for 36 miles to its terminus

at Wheeling there are no features of special interest which I

now recall. The last rail completing the track to that point,

was laid an the eve of Christmas, 1852, and early in the next

month, January, 1853, the formal opening of the road to Wheeling

took place.

And now ere I conclude an address which has, I fear, already

taxed your patience, a word or two of the man who brought this

great work to a conclusion.

Mr. Latrobe was identified with the Baltimore & Ohio R.

R. almost from the very beginning. He had been intended for the

law, but after completing his course of study, and being admitted

to the Maryland bar, concluded that railway engineering was more

to his taste.

He entered the service as an assistant to Mr. Knight, and I

am quite satisfied that Mr. Knight, in all his career, never had

a more faithful one. None could have been more loyal than he,

and when he was no longer an assistant, but himself the Chief,

his modesty was as marked as before.

Whilst his was the mind which planned and directed all, one

might have supposed that the Ideas emanated from the assistants,

so ready was he to give them credit for their well executed details.

He took pride in the work with which he had been so long identified.

He never could have accepted a retainer to oppose its interests,

whether he was on its pay-roll or not. He left behind him in that

portion of the Baltimore & Ohio R. R. which he built a monument

to his professional skill, and in the hearts of his assistants,

a loving remembrance not soon to he effaced.

B & O RR

| Antebellum RR | Contents

Page

This page originally appeared on Thomas Ehrenreich's Railroad Extra Website

|