A JUNE JAUNT

WITH SOME WANDERINGS IN THE FOOTSTEPS

OF WASHINGTON, BRADDOCK,

AND THE EARLY PIONEERS.

Also Cumberland and Piedmont Coal Region

by BRANTZ MAYER—Harper's Monthly—April,

1857

WHEN Madame

de Sevigné exclaimed, in the joy of her heart, "A

journey to make, and Paris at the end of it!" she uttered

the sentiment of a thorough-paced woman of the world, tired to

death of those dreary old chateaus, which; like so many architectural

poplars, break the monotonous levels of France, with their circular

towers and sugar-loaf spires.

WHEN Madame

de Sevigné exclaimed, in the joy of her heart, "A

journey to make, and Paris at the end of it!" she uttered

the sentiment of a thorough-paced woman of the world, tired to

death of those dreary old chateaus, which; like so many architectural

poplars, break the monotonous levels of France, with their circular

towers and sugar-loaf spires.

Dull and uniform landscapes drive people to towns for the entertainment

of society, and Man, with his manifold diversions, becomes tenfold

more attractive than Nature with her homely russet and step-dame

aspect. It is in this respect that rural life in the United States

presents so much more beauty in its diversified forms; for if

we reject the historical associations connected with most parts

of the Old World, we shall reduce the number of spots upon which

memory lingers, when we cross the Atlantic to our American homes.

Lakes and mountains, plain and upland, rock and river, exist in

picturesque variety in Europe; but long use and overpopulation

have deprived the country of that luxuriant forest-land and virginal

freshness which give Nature most of her charms, release her from

dependence on art, and constitute the peculiar features of our

native scenery.

In former times, when we traveled on horseback or in lumbering

coaches, it mattered little if we went over hills or around them, and, of course, our early engineers were rather careless

whether they ran their roads across meadows or struck into the

mountains. Their main mathematical idea was, that "a straight

line is the shortest between two points." Since the introduction

of railways, the object has always been to avoid elevations, and

keep along the lowlands; to follow river banks on a level with

the sea, and to reduce a journey, if possible, to the tameness

of a canal through the marshes of Holland. It has only been of

late that bolder minds have ventured to restore romance to travel

by scaling the Alleghanies with steam-engines, and making a jaunt

through our upland dells and forests as great a delight as it

was to those who first penetrated our wilderness.

But, with all

this improvement, there has been one drawback. The daring that

ventured to disregard mountains has added to the speed with which

their scenery is passed, so that, with increased rapidity, little

time is allowed to observe the added objects of interest. "Going

by rail," says Ruskin, in his last volume, "I do not

consider to be traveling at all; it is merely 'being sent' to a place, and very little different from being a parcel.

A man who really loves traveling would as soon consent to pack

a day of such happiness into an hour of railroad, as one who loved

eating would agree to concentrate his dinner into a pill."

Yet, it is quite possible, if we are willing to forego our proverbial

hurry, to enjoy fully the scenery through the highlands of our

interior; for, although we can be transported at the rate

of thirty or forty miles an hour, there is not a company in the

Union that compels a wayfarer to transform himself into a package,

or does not afford resting-places along its route, where travelers

may linger as long as they please, to be taken up by fresh trains

and forwarded to new spots of interest or beauty. In this way

rapidity has its advantages. It skips us over the dull, and stops

us at the interesting. Fine scenery, like pâté de foie gras,could never be enjoyed if we devoured it constantly,

so that while steam is slurring us over the tame, it is whetting

our appetites for fresh enjoyments at the ensuing pause.

But, with all

this improvement, there has been one drawback. The daring that

ventured to disregard mountains has added to the speed with which

their scenery is passed, so that, with increased rapidity, little

time is allowed to observe the added objects of interest. "Going

by rail," says Ruskin, in his last volume, "I do not

consider to be traveling at all; it is merely 'being sent' to a place, and very little different from being a parcel.

A man who really loves traveling would as soon consent to pack

a day of such happiness into an hour of railroad, as one who loved

eating would agree to concentrate his dinner into a pill."

Yet, it is quite possible, if we are willing to forego our proverbial

hurry, to enjoy fully the scenery through the highlands of our

interior; for, although we can be transported at the rate

of thirty or forty miles an hour, there is not a company in the

Union that compels a wayfarer to transform himself into a package,

or does not afford resting-places along its route, where travelers

may linger as long as they please, to be taken up by fresh trains

and forwarded to new spots of interest or beauty. In this way

rapidity has its advantages. It skips us over the dull, and stops

us at the interesting. Fine scenery, like pâté de foie gras,could never be enjoyed if we devoured it constantly,

so that while steam is slurring us over the tame, it is whetting

our appetites for fresh enjoyments at the ensuing pause.

A party which was made up in Baltimore last spring to go from

that city by rail to the Ohio, along much of the. route which

was pursued by the early pioneers with their pack-horses and caravans,

enjoyed this mode of travel about as perfectly as it is possible.

We were ten in number; and the officers of the Baltimore and Ohio

Railway, knowing our desire to examine several points of historical

interest in that region, were kind enough to invite us to Join

a special train, which was to make a patient reconnaissance of

the road.

It is difficult to imagine any thing better contrived for the

purpose than the equipment which was prepared to secure comfort

and risk from accident. The engine was, one of the best on the

line, and the engineers and conductors were selected for their

experienced skill. After the engine followed a car, fitted up

partly as kitchen and partly as dining-room, where fifteen or

twenty could take their meals as comfortably as in the cabin of

a packet; then came two cars with reading-rooms, writing-tables,

books, instruments, and every thing requisite for the reconnoitering

party, while portions were fitted up with state rooms for accommodation

at night; and, last of all, followed a car with convenient seats

and abundant room for observation. In the forward part of this

train, in charge of the "Commissary Department," were

several excellent waiters, of high repute in their useful sphere;

so that I doubt whether a party started this summer in any quarter

of our country, in quest of health or diversion, better fortified

against the "ills that flesh is heir to."

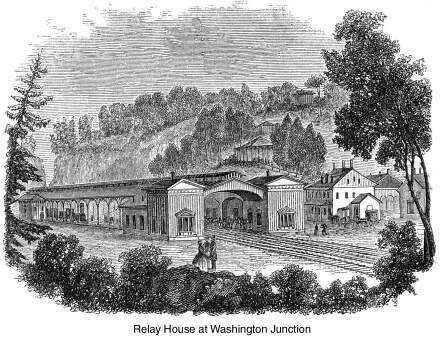

The 24th of June was a fresh, bracing day, when we assembled

at half-past six in the morning at the spacious depot, which is

near completion, and were speedily off over the lowlands to the

Relay House, where we breakfasted on the Maryland luxuries of

"soft-crabs" and "spring-chickens"—two

delicacies which the unenlightened may get an idea of if they

can imagine the luscious flavor of solidified cream browned over

a hickory fire in clover-scented butter.

The Relay House is the first spot where one observes the broken

country through which so much of this road lies, for it is situated

on the rise of the hills, near the place known as Elk Ridge Landing,

to which vessels of considerable tonnage came, in  the early days of Maryland, to load with

tobacco for European markets. In consequence of diminished water,

it has lost its ancient bustle and importance as a port of entry,

and the Patapsco breaks through its picturesque gorge, with greatly

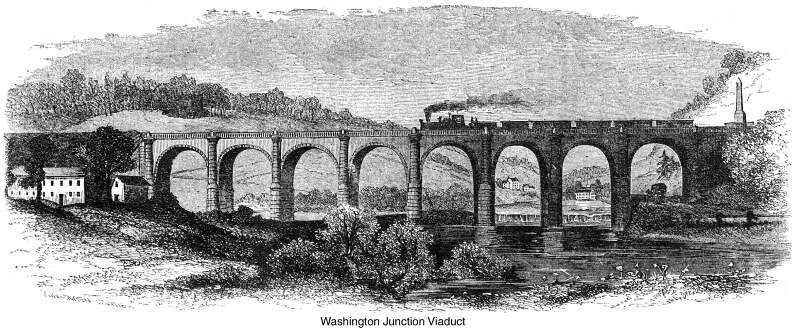

shrunken volume, to find its way to the Chesapeake. Here the railway

branches to the West and to Washington; the latter track crossing

the ravine on a tall viaduct of granite, and .the former pursuing

a beautiful and broken ledge of the stream toward its head-waters

in the hills. The imposing structure which spans the river with

eight arches of sixty feet chord, at a height of sixty feet above

the Patapsco, was one of the early designs of that distinguished

engineer Benjamin H. Latrobe, under whose direction the road has

been completed across the Alleghanies to the Ohio. In order to

obtain a better view of this massive structure, which harmonizes

so completely in color and dimensions with the scenery, we descended

to the water's edge, where, framed like a picture in the granite

arches, the valley opened westward, with its sloping hills, villa-studded

groves, and placid river, and the Avalon Works relieved against

the sky in the remote gap.

the early days of Maryland, to load with

tobacco for European markets. In consequence of diminished water,

it has lost its ancient bustle and importance as a port of entry,

and the Patapsco breaks through its picturesque gorge, with greatly

shrunken volume, to find its way to the Chesapeake. Here the railway

branches to the West and to Washington; the latter track crossing

the ravine on a tall viaduct of granite, and .the former pursuing

a beautiful and broken ledge of the stream toward its head-waters

in the hills. The imposing structure which spans the river with

eight arches of sixty feet chord, at a height of sixty feet above

the Patapsco, was one of the early designs of that distinguished

engineer Benjamin H. Latrobe, under whose direction the road has

been completed across the Alleghanies to the Ohio. In order to

obtain a better view of this massive structure, which harmonizes

so completely in color and dimensions with the scenery, we descended

to the water's edge, where, framed like a picture in the granite

arches, the valley opened westward, with its sloping hills, villa-studded

groves, and placid river, and the Avalon Works relieved against

the sky in the remote gap.

The road turns

around a bluff on quitting the Relay House for the West. It leaves

the viaduct on the left, passes the Avalon Iron Works, and skirting

the river for six miles, reaches the village of Ellicott's Mills.

Throughout this transit there is charming variety of hill, rock,

and river scenery, interspersed with continual evidences of agricultural

and manufacturing industry, the whole overshadowed at this season

by fresh foliage among the granite which abounds in this district.

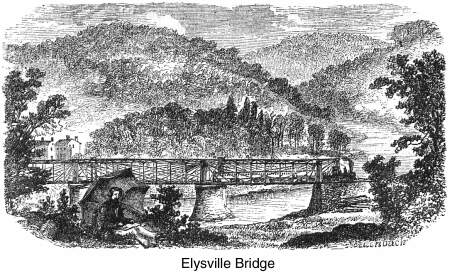

From the Relay House to Ellicott's Mills, and thence onward to

Elysville, the Patapsco gradually narrows and brawls over a rocky

bed, affording valuable water-power which has been prosperously

employed. We halted at Elysville for a short time to examine the

peculiarities of an iron bridge invented by Mr. Wendel Bollman,

of Baltimore, spanning the Patapsco with a double track of three

hundred and forty feet. There are so many valuable elements of

strength, security, and permanence in this invention, that I would

be glad to describe it minutely; but towers, chords, cores, tenons,

rivets, sockets, suspension rods, and their scientific combinations,

afford but dull entertainment for general readers, and, accordingly,

I must refer the more curious to the ingenious artist himself,

whenever they desire to promote the safety of railways by counteracting

the evil effects of expansion and contraction, which have been

so disastrous to many of the iron bridges of our country.

The road turns

around a bluff on quitting the Relay House for the West. It leaves

the viaduct on the left, passes the Avalon Iron Works, and skirting

the river for six miles, reaches the village of Ellicott's Mills.

Throughout this transit there is charming variety of hill, rock,

and river scenery, interspersed with continual evidences of agricultural

and manufacturing industry, the whole overshadowed at this season

by fresh foliage among the granite which abounds in this district.

From the Relay House to Ellicott's Mills, and thence onward to

Elysville, the Patapsco gradually narrows and brawls over a rocky

bed, affording valuable water-power which has been prosperously

employed. We halted at Elysville for a short time to examine the

peculiarities of an iron bridge invented by Mr. Wendel Bollman,

of Baltimore, spanning the Patapsco with a double track of three

hundred and forty feet. There are so many valuable elements of

strength, security, and permanence in this invention, that I would

be glad to describe it minutely; but towers, chords, cores, tenons,

rivets, sockets, suspension rods, and their scientific combinations,

afford but dull entertainment for general readers, and, accordingly,

I must refer the more curious to the ingenious artist himself,

whenever they desire to promote the safety of railways by counteracting

the evil effects of expansion and contraction, which have been

so disastrous to many of the iron bridges of our country.

We wound westwardly from Elysville five miles till we struck

the fork of the Patapsco, when we turned its western branch, passed

the Mariottsville quarries, crossed the river on an iron bridge

of fifty feet, ran through a tunnel four hundred feet long, and

hurrying across meadowlands, followed a crooked gorge to Sykesville

in the heart of a region abounding in minerals. For a considerable

distance beyond this settlement we traversed a rough, level country—our

road, for the most part, cut from the solid rock—till, leaving

the region of granite, it shortly struck Parr's Ridge, which divides

the Valley of the Patapsco from that of the Monocacy and Potomac.

From the top of this elevated grade there are superb views of

the Plains of Frederick, backed by spurs of the Blue Ridge, which

stand out like advanced sentinels in the midst of luxuriant farm-land.

On its western side the quiet Monocacy waters a rural district

till it issues by a gorge, and coasts the eastern slopes to the

termination of the mountains. Near the mouth of this placid stream,

the insulated masses of Sugar-loaf Mountain shoot up abruptly;

while, on the other side, the slopes, spurs, and transverse valleys

are dark with magnificent groves of choicest timber.

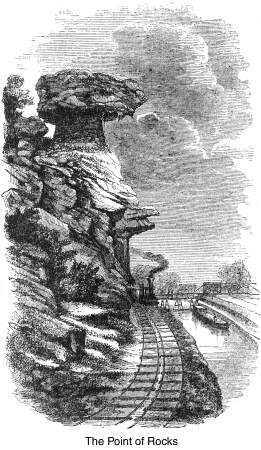

With such scenery on all sides, we passed the Monocacy, and,

quitting its valley, crossed, southwestwardly, over limestone

levels, between the Catoctin and Sugar Loaf, and struck the Potomac

at no great distance from the Point of Rocks, where the railway

runs on a ledge cut from the precipice of the Catoctin Mountain,

towering up on the right, and supported by broad embanking walls

that separate it from the canal and river on its left.

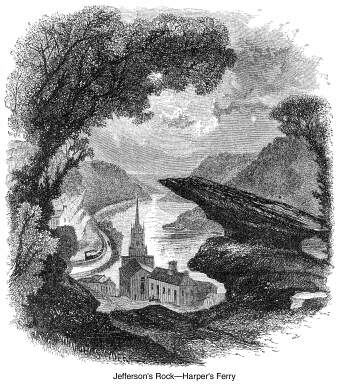

The Potomac, at this point, is a third of a mile wide, and

foams over a bed of ledges crossing it at right angles like so

many fractured barriers, denoting the conflict between the ridge

and river when it burst through the hills, Such, with few intermissions,

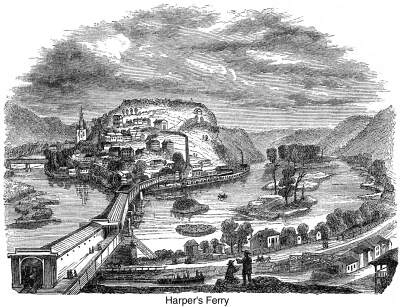

is the character of scenery from the Point of Rocks to Harper's

Ferry, which is built on a narrow, declivitous tongue, lying  directly in the confluence

of the Shenandoah and Potomac, and washed on either side by those

noble streams. The railway reaches it by a stupendous curving

bridge of nine hundred feet over the latter; and as the mountain

steeps converge precipitously at all points about the gap, but

small space is left for building with accessible convenience.

Nearly all the level river-margin has been used for the National

Armory, so that the town scrambles picturesquely among the upland

bluffs, till the hill-top, like the end of all things, is terminated

by the groves and monuments of a cemetery.

directly in the confluence

of the Shenandoah and Potomac, and washed on either side by those

noble streams. The railway reaches it by a stupendous curving

bridge of nine hundred feet over the latter; and as the mountain

steeps converge precipitously at all points about the gap, but

small space is left for building with accessible convenience.

Nearly all the level river-margin has been used for the National

Armory, so that the town scrambles picturesquely among the upland

bluffs, till the hill-top, like the end of all things, is terminated

by the groves and monuments of a cemetery.

Our first visit was to the Armory, where we were introduced

to all the mysteries in this wonderful assemblage of contrivances

for death. Every thing was exhibited and set in motion—from

the ponderous tilt-hammers, which weld steel into solidity, down

to the delicate operations by which the impulse of a hair can

put these terrible engines in action. I was soon struck by the

fact that, after all, it is not so easy to kill a man—especially,

if we consider the intricate preparations which have to be made

in constructing weapons for human slaughter. We learned that a

musket consists of forty-nine pieces, and that the number of operations

in completing one—each of which is separately catalogued

and valued—amount to three hundred and forty-six; all, in

some degree, requiring different trades and various capacities

for execution; so that, perhaps, no man, or no two men in the

establishment, could perform the whole of them in manufacturing

a perfect weapon!

I confess that, with but little turn for mechanical science,

most of these complicated machines were rather surprising than

comprehensible to me; so that, while my companions strolled through

the apartments in quest of instruction, I followed leisurely in

their rear, rather grieving than glorying in the inventive skill

that had been lavished on their construction under national auspices.

It may be considered more sentimental than practical in the present

belligerent state of mankind, to doubt the wisdom of making military

preparations under the amiable name of "defense" yet I have never been able to understand why it should not

be "constitutional" to create as well as to kill, and

to make a sickle as well as a sword! Why is it that political

law allows millions for the belongings of war, and denies a dollar

to those genial arts which, in ten years, would do more for the

progress of  humanity

than centuries of traditionary force have effected for its demoralization?

Nay, how much more beneficially would these hundreds of workmen

be employed, if government devoted their labor to the manufacture

of such unpicturesque instruments as hoes, spades, rakes, axes,

pitchforks, plows, and reaping machines; and if the army, which

is to wield the perilous weapons that axe strewn in every direction,

were transmuted, under national patronage, into cultivators of

those "homesteads" which politicians so cheaply vote

them! But, alas! the soldier is epic, and the farmer only pastoral,

and pageantry beats homeliness all the world over!

humanity

than centuries of traditionary force have effected for its demoralization?

Nay, how much more beneficially would these hundreds of workmen

be employed, if government devoted their labor to the manufacture

of such unpicturesque instruments as hoes, spades, rakes, axes,

pitchforks, plows, and reaping machines; and if the army, which

is to wield the perilous weapons that axe strewn in every direction,

were transmuted, under national patronage, into cultivators of

those "homesteads" which politicians so cheaply vote

them! But, alas! the soldier is epic, and the farmer only pastoral,

and pageantry beats homeliness all the world over!

These lackadaisical fancies floated through my mind as I walked

over the half mile of armory; and I hope I may not be set down

as "too progressive" or "Utopian," if I divulge

them in this public confessional.

It was noon when we left the Armory and climbed to the fragment

of Jefferson's Rock, which affords the best coup d'oeil of this celebrated scenery. It was a fatiguing tramp under

a mid-day sun, but we found a breeze singing down the gorge of

the Shenandoah when we rested under the old pine-tree among the

cliffs. The rock itself is of very little interest, except for

its association with Mr. Jefferson's name, and its remarkable

poise on a massive base. The drawing at the beginning of this

article presents an accurate view of the whole scene. From the

gap between the fragments the prospect combines the grand and

beautiful in a wonderful degree. Beyond the brow of the hill very

little of the town is seen to disfigure the original features

of the prospect, so that the wilderness of mountain, forest, and

water may still be as freshly enjoyed as they were by the earliest

travelers. Indeed it is impossible for language to sketch the

spirit of the spot more vividly than is done in the bold penciling

of Jefferson. "You stand,'' says he, "on a very high

point of land; on your right comes up the Shenandoah, having ranged

the foot of the mountain a hundred miles to seek a vent; on your

left approaches the Potomac in quest of a passage also. In the

moment of their junction they rush together against the mountain,

rend it asunder, and pass off to the sea." In a few distinct

words of outline we have the geology and geography of the spot

before us; but when the sun is lower and the shadows broader than

at the time of our visit, so as to impart variety of tone and

effect to the scene, it is difficult to conceive a wilder prospect

than the mountains forming the gap, or a more placid landscape

than that which waves away beyond it, till hill, forest, and river

fade in the east. There is a remarkable contrast between the roughness

of the foreground and the pastoral quiet of the distance, so that

the very landscape seems to teach the need and harmony of repose

after struggle.

We dined in the cars as they rolled along slowly to Martinsburg,

where we tarried for the night after a stroll through the ancient,

hospitable town, examining the extensive work-shops and establishments

connected with the railway. Martinsburg is the centre of a rich

country in the hands of generous proprietors, and the converging

point of considerable trade between the mountain foot and sea-board.

We were up betimes on the morning of the 25th; for our hotel

was near the track, and the incessant passage of trains during

the night was not the most exquisite anodyne for tired travelers.

I do not remember any striking scenery till we crossed Back Creek

on a stone viaduct with a single arch of eighty feet, and once

more opened the Potomac Valley with views of the North Mountain

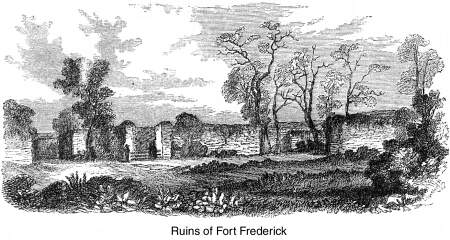

and Sideling Hill in the distance. Beyond this point we stopped

to visit the remains of Fort Frederick, erected by the Colonial

government of Maryland in 1775. The ruins lie north of the river

beyond the canal; so that it was necessary to descend the steep

sides of the mountain glen, still covered with the original forest,

and cross a lake-like reach of the Potomac in batteaux to

the opposite shore, where we found the military wreck on the upper

levels of the river bank, about a quarter of a mile from its embowered

margin. The fort stands in the midst of cultivated fields, while

a wholesome-looking barn nestles under its dismantled walls. The

fortification is a square, with salient angles or bastions at

the four corners, and rises to the height of about fifteen feet.

There are no embrasures for cannon, nor is the structure massive

enough to resist artillery; but as it was built for frontier defense,

it was probably rather a garrison for riflemen than a regular

fortress capable of sustaining an attack of disciplined troops.

The four substantial walls have been little harmed in the lapse

of a hundred years. Their interior is overgrown  with weeds and bushes; the magazine is

a heap of stones; the barracks have disappeared altogether; the

gates are gone; large trees flourish in the corner bastions; ivy

grows over portions of the wall; but, with all these evidences

of decay, we were glad to hear that the farmer on whose land it

stands does not allow a stone to be removed, and is determined

to preserve it as a historical relic of our Maryland forefathers.

The only inhabitant we found in the abandoned fort was a black

snake of considerable size; but as he was speedily slain by some

of our followers, I suppose the last emblem of hostility has been

destroyed within the walls, and the gray ruin left to the innumerable

thrushes that were singing in its solitude.

with weeds and bushes; the magazine is

a heap of stones; the barracks have disappeared altogether; the

gates are gone; large trees flourish in the corner bastions; ivy

grows over portions of the wall; but, with all these evidences

of decay, we were glad to hear that the farmer on whose land it

stands does not allow a stone to be removed, and is determined

to preserve it as a historical relic of our Maryland forefathers.

The only inhabitant we found in the abandoned fort was a black

snake of considerable size; but as he was speedily slain by some

of our followers, I suppose the last emblem of hostility has been

destroyed within the walls, and the gray ruin left to the innumerable

thrushes that were singing in its solitude.

Beyond Fort Frederick, we began to touch the region of St.

Clair, Braddock, and Washington. West of Hancock, we halted at

Sir John's "Run," whence a short, brisk drive deposits

travelers at Berkeley Springs, whose virtues were recognized at

an early day by Washington and the Fairfaxes, and continue to

be acknowledged every summer by crowds from Maryland and Virginia.

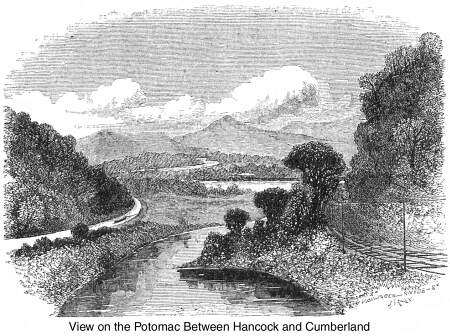

The Valley of the Potomac has nearly the same characteristics

through its whole length, from this place to Cumberland. The road

winds along the stream, and about the base of mountain spurs—some

rising suddenly in distinct cones, and others broken into steep

cliffs, displaying their strata-like layers of masonry. Sideling

Hill, Tower Hill, and Green Ridge are consecutively passed, till,

in the neighborhood of Warrior Mountain, we pass into beautiful

meadow-lands which are of historic interest on the line of travel

between the sources of the Patapsco and the head-waters of the

Ohio.

It was to this charming valley, sheltered by the first spurs

of the Alleghanies, that the celebrated Colonel Thomas Cresap

removed, about 1742, from the neighborhood of the Susquehanna,

and established himself in the homestead which our artist has

sketched, and which is still owned and occupied by his descendants.

Some five

years afterward, when Washington was in his seventeenth year,

Lord Fairfax dispatched the enterprising youth on his "surveying

expedition" to this region; and, among his early experiences

in woodcraft he records that, "after vainly watching for

the river to subside from an unusual freshet, he crossed the Potomac

in a canoe, from the neighborhood of Bath, and reached the Colonel's

house, opposite the South Branch, by a weary ride of forty miles,

in continual rain, over the worst road ever trod by man or beast."

Here he tarried several days for fair weather, and was entertained

by the savage sports of an Indian war-party, whose wild propensities

were probably subdued by the judicious application of a little

grog!

Some five

years afterward, when Washington was in his seventeenth year,

Lord Fairfax dispatched the enterprising youth on his "surveying

expedition" to this region; and, among his early experiences

in woodcraft he records that, "after vainly watching for

the river to subside from an unusual freshet, he crossed the Potomac

in a canoe, from the neighborhood of Bath, and reached the Colonel's

house, opposite the South Branch, by a weary ride of forty miles,

in continual rain, over the worst road ever trod by man or beast."

Here he tarried several days for fair weather, and was entertained

by the savage sports of an Indian war-party, whose wild propensities

were probably subdued by the judicious application of a little

grog!

Washington's family had known Cresap when he lived in Eastern

Maryland, and the stout pioneer was soon employed in his new quarters

by the principal persons interested in the Ohio Land Company,

which had received a grant of 500,000 acres beyond the Alleghanies,

between the Monongahela and Kanawha. The object of this enterprise

was to settle land and develop the West. The French, who regarded

the Valley of the Mississippi as their own, became alarmed at

this inroad on their asserted borders, and extended a line of

military posts throughout the West, embracing a vast extent of

territory claimed by Great Britain. In spite of all opposition,

the British grantees pursued their enterprise zealously, from

what was then the heart of our Eastern settlements, and Cresap's

knowledge of the country and frontier-life was of immense service

in tracing and keeping open the first path over the Alleghanies

to Red Stone Old Fort—the modern Brownsville. As one of the

company's agents, he employed Nemacolin, a friendly Indian, to

mark and clear a way along the trail of the tribes, and he performed

his duty so well that Braddock pursued the route when he marched

to dislodge the French from Fort Duquesne.

But those were

days in which no questions were asked, in such lonely outposts,

save at the rifle's mouth; and, of course, Cresap and his family

often became engaged in struggles with the savages, who were roused

by the French. The mountains and neighboring lowland swarmed with

these guerrilleros, and the pioneer took the "war-path,"

in Indian fashion, with his children and retainers, striking the

foe at the western foot of Savage Mountain, where his son Thomas

fell; and at Negro Mountain, farther west, where a gigantic African,

who belonged to the party, bequeathed his name, in death, to the

towering cliffs. Dan's Mountain, in the neighborhood of Savage,

received its title from some hardy exploits of his son Daniel;

and it was amidst scenes of danger like these that Captain Michael

Cresap—so unjustly charged with the murder of Logan's family—was

brought up, and obtained his early lessons in Indian warfare.

But those were

days in which no questions were asked, in such lonely outposts,

save at the rifle's mouth; and, of course, Cresap and his family

often became engaged in struggles with the savages, who were roused

by the French. The mountains and neighboring lowland swarmed with

these guerrilleros, and the pioneer took the "war-path,"

in Indian fashion, with his children and retainers, striking the

foe at the western foot of Savage Mountain, where his son Thomas

fell; and at Negro Mountain, farther west, where a gigantic African,

who belonged to the party, bequeathed his name, in death, to the

towering cliffs. Dan's Mountain, in the neighborhood of Savage,

received its title from some hardy exploits of his son Daniel;

and it was amidst scenes of danger like these that Captain Michael

Cresap—so unjustly charged with the murder of Logan's family—was

brought up, and obtained his early lessons in Indian warfare.

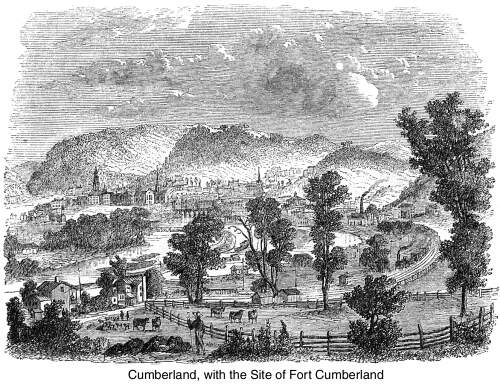

We reached Cumberland, in a brisk shower, about four o'clock;

but were soon relieved from anxiety as to accommodations by our

generous friends in this charming city. We should do violence

to their feelings if we spoke publicly of what is habitual with

them and characteristic of the country; but we should equally

violate ours if we avoided the expression of gratitude for a pleasant

season in Cumberland, spent in the midst of unostentatious people

and "old Maryland hospitality."

Soon after

sunrise on the 26th, we joined a special train, belonging to the

Eckhart Mining Company, to visit the coal region for which Maryland

is becoming celebrated all the world over.

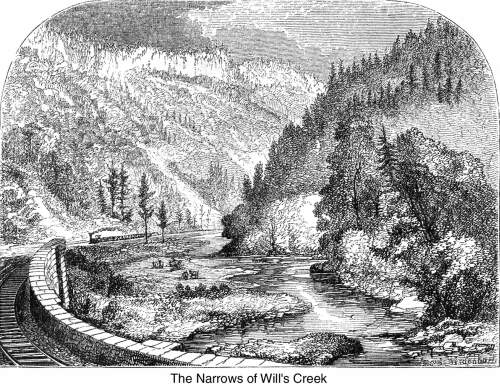

In days of old, the mountains which rise abruptly in the west,

1800 or 2000 feet above the level of Cumberland, probably extended

northwestwardly in an unbroken wall, till some of those great

convulsions which formed the water gaps of the Delaware and Potomac

let loose the pent-up floods on their way to the sea. It was through

one of these gigantic chasms in the chain that we penetrated the

Alleghanies toward the coal region. The "Narrows of Wills's

Mountain," is the outlet of Braddock's, Wills's, and Jennings's

Runs, which nearly converge at this point on the western slope,

and, by their united force in the early day, burst open this splendid

gap, which extends for more than a mile, five hundred feet wide,

with precipitous walls of near nine hundred!

The strata throughout

this chasm were laid bare by the original fracture. In portions

the lines of grayish sandstone are nearly vertical, as if mashed

against the flank of the mountain. A scant vegetation of creepers

and bushes has sprung up in the clefts, and in many places broken

rocks, tumbled confusedly from the mountain-top, have filled the

edges of the gorge with heaps of Cyclopean fragments.

The strata throughout

this chasm were laid bare by the original fracture. In portions

the lines of grayish sandstone are nearly vertical, as if mashed

against the flank of the mountain. A scant vegetation of creepers

and bushes has sprung up in the clefts, and in many places broken

rocks, tumbled confusedly from the mountain-top, have filled the

edges of the gorge with heaps of Cyclopean fragments.

Passing through this wilderness of romantic disorder, we seem

to enter the very core of the mountains, piled up on all sides

in wooded slopes and narrow valleys. Directly in front is Dan's

Mountain, while west of it rise the higher and darker summits

of the Savage. Between these two mountains, extending in length

twenty miles in Maryland, with an average breadth of four, is

the site of the celebrated coal basin, traversed by a ridge or

upland glade, dividing it into two unequal parts. This valuable

mineral field is fifteen hundred feet above tidewater, and nearly

a thousand above Cumberland. It is not horizontal in its strata,

but gets its name of "basin" from the trough-like curvature

of the veins, whose formation may be comprehended by imagining

the process of their original disturbance by volcanic action.

Those rock-herbariums, the fossils, demonstrate that coal is

the result of buried vegetation. It is presumed that the great

Alleghanian field was the bed of an ancient lake, which has been

drained by the Mississippi, Susquehanna, St. Lawrence, and Hudson,

as the head waters of the Alleghany, Genesee, Susquehanna, Chesapeake,

and St. Lawrence, take their rise within an area of five miles.

If we imagine the original bed of this basin to have been formed

by separate deposits of coal, iron, limestone, and other materials,

lying horizontally on each other, and the tops of the present

mountains to have been nearly on a line with these levels, we

shall obtain an accurate idea of the mode in which the strata

were bent into curves by the upheaval of Dan's Mountain on the

cast, and Savage Mountain on the west, bearing with them as they

rose the skirts of the strata, while they left their centres undisturbed.

The most reliable

information as to the quantity of this mineral, diffuses it over

an area of about a hundred and fifty square miles; and in the

best mines, it is calculated that from eleven thousand to thirteen

thousand tons may be produced from every, acre.

The most reliable

information as to the quantity of this mineral, diffuses it over

an area of about a hundred and fifty square miles; and in the

best mines, it is calculated that from eleven thousand to thirteen

thousand tons may be produced from every, acre.

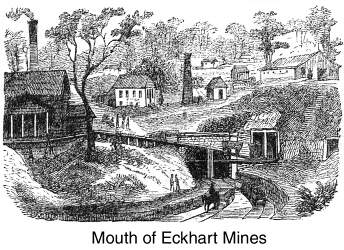

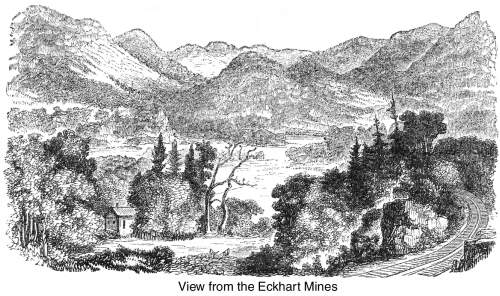

Our ascent to the Eckhart mines by rail and locomotive was

my first adventure of the character, and I must confess, that

although we rose many hundred feet in the space of eight or nine

miles, I experienced none of those startling sensations which,

in recent accounts of mountain roads, have made our heads dizzy

with imaginary terror. The company which we visited on this occasion

appears to be one of the most prosperous in the district, owning

a railway, several villages, ten thousand acres of coal land,

immense quantities of timber and farming country, and employing

about six hundred workmen.

I had so often visited the interior of mines that I did not

accompany my friends when, furnished with candles and forming

a sort of dismal procession, they entered the mouth of the mine

and twinkled away in its dark perspective like so many expiring

sparks. I sat down on the hill above the entrance, and, for an

hour or more, enjoyed the air of the hills and the superb panorama

of mountain, valley, and forest, with its broad masses of light,

shadow, verdure, and blue overlapping distance. The prospect is

not bounded by an extremely remote horizon, as is the case from

some higher points, but there is still sufficient elevation and

extent to afford most of the fine mountain effects that are to

be found throughout the Alleghanies.

After the return of our companions (who came forth from the

bowels of the earth limp and hungry, but extremely learned on

the mysteries of mining), and a hearty refection at the hospitable

board of Mr. Henderson, carriages and horses were put in requisition

to pass the central ridge which binds Dan's Mountain to Savage

Mountain. A pleasant drive of an hour over the  breezy upland, through the forest, took

us to a vestige of Braddock's Road, which the patriotic owner

has fenced in, for fifteen or twenty yards, as a post-and-rail

monument to the defeated General? The army's route may still be

traced through the woods over the mountains; and on its course,

at no great distance from the inclosure, there is still an ancient

stone which indicates the number of miles to Red Stone Old Fort,

and terminates with the valorous legend of—

breezy upland, through the forest, took

us to a vestige of Braddock's Road, which the patriotic owner

has fenced in, for fifteen or twenty yards, as a post-and-rail

monument to the defeated General? The army's route may still be

traced through the woods over the mountains; and on its course,

at no great distance from the inclosure, there is still an ancient

stone which indicates the number of miles to Red Stone Old Fort,

and terminates with the valorous legend of—

"Our country's rights we will defend!"

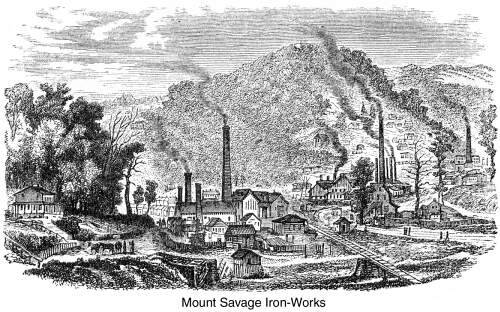

We passed rapidly through Frostburg, a fresh mountain village,

flourishing under the impetus of an increasing neighborhood; and

striking off to the left, wound slowly down for several miles

of forest glen, along the margin of Jennings's Run, to the works,

where the Mount Savage Company is engaged in the manufacture of

iron.

Its proprietors own five thousand acres of timber and mineral

land; three blast furnaces, capable of producing four hundred

tons of pig iron per week; several forges; rolling mills, equal

to the furnishing ten thousand tons of rail per annum; a foundery;

machine shops; a fire-brick factory, yielding thirteen hundred

thousand a year; and three hundred dwellings for the uses of the

establishment, which, when in full blast, gives employment to

nearly a thousand people. Besides these large elements of wealth,

the Company owns the Cumberland and Pennsylvania Railroad (worked

under a distinct charter), connecting its village with Frostburg,

and descending to Cumberland by a grade of eleven hundred feet.

We found these works under the personal superintendence of the

president, Mr. John A. Graham; and the. road under the care of

Mr. Slack, to whom we were indebted for marked attention during

our brief visit to the country.

It was a scorching day in the narrow valley through which the

sun poured down with all its natural and reflected heat; but we

penetrated the sweltering furnace and rolling mill, where we saw

all the ponderous operations by which the blazing metal is rolled

into bars to bear the freight and travel of our country.

In the midst

of all these industrial pursuits, the quiet mountain-sides have

been dotted, in romantic situations, with the seats of enterprising

persons who set all this enginery in motion; and a visitor is

transported from the rough scenes I have mentioned to elegant

residences, filled with every attraction that refinement and hospitality

can require. Cultivated society is wreathing the tops of these

wild old mountains with a garland of delicious homes, and I can

hardly doubt that in a few years the allurements of sport and

scenery, as well as the lucrative pursuits of trade, will make

these noble uplands the abode of thousands.

In the midst

of all these industrial pursuits, the quiet mountain-sides have

been dotted, in romantic situations, with the seats of enterprising

persons who set all this enginery in motion; and a visitor is

transported from the rough scenes I have mentioned to elegant

residences, filled with every attraction that refinement and hospitality

can require. Cultivated society is wreathing the tops of these

wild old mountains with a garland of delicious homes, and I can

hardly doubt that in a few years the allurements of sport and

scenery, as well as the lucrative pursuits of trade, will make

these noble uplands the abode of thousands.

We left our carriage at Mount Savage, and returned by the company's

railway along a more southerly route than the one we pursued on

our way to the Eckhart Mines. The scenery throughout was strikingly

picturesque; there were some distant glimpses of mountain and

valley; but the road was mostly confined to narrow dells, whose

precipitous sides were of the same broken wall-like character

as the masses through which we entered the mountains in the chasm

of Wills's Creek.*

* We had time to visit only one coal-mine, and the iron-works.

There are many other companies in this region, among which I recollect

the New York Mining Company; the Maryland, the Alleghany, the

Borden, the Wither's, the Astor, the Cumberland Coal and Iron

Company, the Washington Coal Company, the Frostburg Coal Company,

the New Creek Company; the American, the Swanton, the Hampshire,

the George's Creek Coal and Iron Company, etc., etc., etc.

I know few inland towns more charmingly situated than Cumberland,

on the slope of a superb amphitheatre, with its background of

mountains, approached through vistas of forest-covered spurs.

From the earliest times its geographical position at the foot

of the Alleghanies, as the central point between the navigable

waters of the east and west, made it attractive to our military

and commercial people.

Old Fort Cumberland was built there because it was the frontier

outpost on the Indian trail; Braddock made it the rendezvous of

his luckless enterprise for the same reason; our forefathers established

it as the entrepot for trade with the hunters, trappers, and settlers

of the West; by general consent it became the route of the National

Road; and, ever since the days of the Revolution, there is hardly

a traveler from the sea-board to the West who has not breakfasted,

dined, supped, or changed horses at Cumberland.

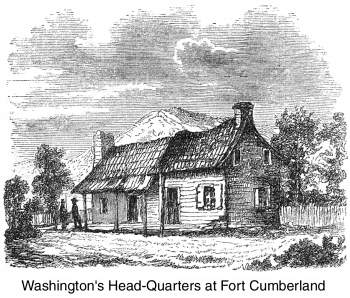

Most of the old historic traces have been obliterated by the

growth of the town since the opening of the adjacent mines and

the completion of canal and railway. We visited the site of Old

Fort Cumberland on the afternoon of our arrival. The rounded knob

of a hillock rises from the stream which winds about its base

with a short curve, so as to afford hardly more room than is  necessary for a broad

walk around the Gothic Church, which occupies the site of the

fort, and "whose canons" as a joker said, "have

displaced the cannons of the fort." A depression in

the ground marks the old well as the sole survivor of the military

past. Until 1846 or 1847, the weather-beaten hovel which Washington

occupied as his quarters more than a hundred years ago, still

stood behind the fort in the rickety rain delineated by our artist;

but it has been removed to make way for a modern dwelling.

necessary for a broad

walk around the Gothic Church, which occupies the site of the

fort, and "whose canons" as a joker said, "have

displaced the cannons of the fort." A depression in

the ground marks the old well as the sole survivor of the military

past. Until 1846 or 1847, the weather-beaten hovel which Washington

occupied as his quarters more than a hundred years ago, still

stood behind the fort in the rickety rain delineated by our artist;

but it has been removed to make way for a modern dwelling.

On Green Street there are two houses—said to have been

built by Braddock—constructed of stout timber, heavily ironed

and riveted on both sides. One, from the manner in which its doors

are made, is supposed to have been a jail; the other a two-story

log and weather-boarded edifice—still goes by the name of

Braddock's Court. Washington was here in 1753, '54, '56; and by

a journey of forty or fifty miles over the National Turnpike,

the earliest scenes of his military life may be visited in the

neighborhood of the Great Meadows, where Braddock died and was

buried in the forest.

It was in that quarter that Washington endured the stern trials

of Fort Necessity (whose outlines may still be traced in the field),

and had his first fight, at the surprise and capture of

Jumonville's party. It was here, too, at the age of twenty-two,

that he declared there was "something charming in

the sound of whistling bullets!" a youthful vaunt for which

Walpole rated him as "a brave braggart;" George the

Second thought "he would have expressed himself differently

if he knew more about them;" and which he himself, in after

years, denounced as the ejaculation of a "very young

man!"

There is another

great artery for trade and travel across this mountain region,

about to be completed, from Cumberland to Pittsburg, through the

heart of the Alleghanies at Connelsville. Our limited time, however,

did not allow us to explore the route in its present rough state—an

expedition we should have been exceedingly glad to make, as it

would have prepared us to appreciate the difficulties already conquered by the same engineer on the road to Wheeling.

There is another

great artery for trade and travel across this mountain region,

about to be completed, from Cumberland to Pittsburg, through the

heart of the Alleghanies at Connelsville. Our limited time, however,

did not allow us to explore the route in its present rough state—an

expedition we should have been exceedingly glad to make, as it

would have prepared us to appreciate the difficulties already conquered by the same engineer on the road to Wheeling.

We left Cumberland by a stone viaduct of fourteen arches, fifty

feet span each, which Mr. Latrobe designed and built over Wills's

Creek, at an elevation of thirty-five feet above the bed of the

stream. As a type of the structures of all classes and for all

purposes along this route—whether machine-shops, engine-houses,

depots, water tanks, or stations—this bridge may be taken

as a striking specimen. In massive solidity it resembles those

noble works of the Empire, whose remains, after the lapse of two

thousand years, still excite our wonder on the Campagna of Rome.

For twenty-two miles we skimmed over a gradually ascending

level, toward the southwest, along the north branch of the Potomac,

which runs between the western slope of Knobly, and the eastern

feet of Dan's and Wills's mountains. The Knobly range, rising

in detached bosses, often slopes gracefully into the rich sward

of the valley, while the stream is fringed by trees and herbage,

till the main Cordillera of the Alleghanies is approached,

and the defiles begin to rise with irregular, abrupt edges, curbing

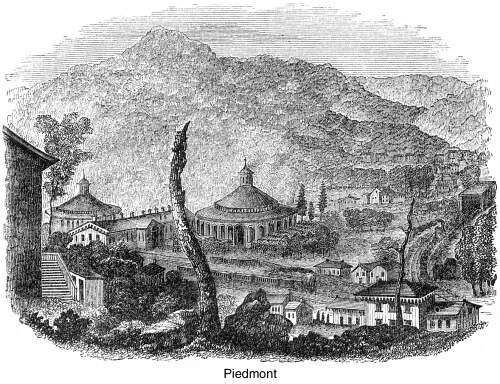

the waters into a gorge. For the last six miles toward Piedmont,

the river lies in a chasm cut by its torrent-like course through

the mountain feet. About twenty-one miles from Cumberland we crossed

the Potomac on a bridge of timber and iron; and then, winding

by easy curves through romantic scenery, as if feeling our way

through approaching difficulties, we passed the  Queen's Cliff, Thunder Hill, and the

steep ledges of Dan's Mountain, and rested in the broad lap of

levels deposited by the mountain wash at Piedmont. This remote

village has sprung up in its solitude at the steep base of the

Alleghanies, as a sort of breathing-place, where the fiery horse

is to pause, gird up his loins, and renew his strength for a struggle

with the giants that stand before him in all their defiant grandeur.

Queen's Cliff, Thunder Hill, and the

steep ledges of Dan's Mountain, and rested in the broad lap of

levels deposited by the mountain wash at Piedmont. This remote

village has sprung up in its solitude at the steep base of the

Alleghanies, as a sort of breathing-place, where the fiery horse

is to pause, gird up his loins, and renew his strength for a struggle

with the giants that stand before him in all their defiant grandeur.

No one, I am sure, has ever looked westward from this spot

without wondering how the passage is to be effected; yet no one

has made the journey without equal surprise at the seeming ease

by which science and energy have overcome every impediment. As

you pass forward from Piedmont, the impression is that you are

about to run a tilt against the mountain flank with blind and

aimless impulse; but a graceful curve winds the train out of harm,

and you move securely into the primeval forest, feeling the engine

begin to tug up the steeps as it strikes the edge of Savage River,

which boils down the western shoulder of Savage Mountain. The

transit from the world to the wilderness is instantaneous. Mr.

Bancroft and I mounted the engine at this spot so as to enjoy

an unobstructed view of the scenery during the ascent; and although

a gust began to growl over the mountains, with frequent flashes

of lightning and thunder, we kept our post, finding the grandeur

of the prospect enhanced by the rush of the storm as we rose higher,

and higher on the mountain flank.

No one has observed fine scenery without acknowledging the

difficulty of its description; for its impression is purely emotional, and emotion is so evanescent that the effort to condense it

into language destroys the sentiment as breath destroys the prisms

of a snow-flake. We may give a catalogue of pines, precipices,

rocks, torrents, ledges, overarching trees, and all the elements

that make one "feel the sublimity of a stern solitude;"

but I have never been able to convey, by words, the exact impression

of such scenes, nor do I believe we can obtain what is somewhere

called "a realizing sense" in the descriptions of others.

In this respect, music and painting have more power than language;

music has the spirituality which painting lacks, and painting

the body in which music is deficient; but, as their effects can

never be completely united, we must despair of influencing the

mind at second hand from Nature.

And so we rolled

resistlessly upward, for seventeen miles, along the broad ledges,

seeing the tree-tops sinking as we swooped into the air, which

freshened as we rose; seeing the vale grow less and less, and

the summits that were just now above us come closer and closer

till we touched their level; seeing the river whence we started

shrink to a film in its bed; and seeing the narrow, upward, imprisoning

glimpse widen into a downward, distant reach.

And so we rolled

resistlessly upward, for seventeen miles, along the broad ledges,

seeing the tree-tops sinking as we swooped into the air, which

freshened as we rose; seeing the vale grow less and less, and

the summits that were just now above us come closer and closer

till we touched their level; seeing the river whence we started

shrink to a film in its bed; and seeing the narrow, upward, imprisoning

glimpse widen into a downward, distant reach.

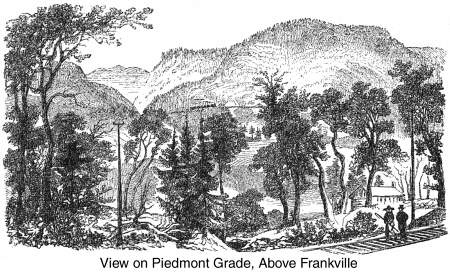

On we hurried without halting but once, till we turned from

the Savage Valley into the Crabtree Gorge, along the flank of

the great Alleghany Backbone; and a few miles above Frankville

(an eyrie among the summits, some 1800 feet above tide, and 1100

feet above Cumberland), cast our eyes back toward the northeast

for a rapid glimpse of one of the grandest views in the mountains.

The gloomy masses of Savage Mountain tower on the right, fold

upon fold, and the eastern slopes of Meadow Mountain, with its

spurs, on the left; while between them the Savage River winds

away for miles and miles in a silvery trail till it is lost in

the distance. Throughout the whole passage from Piedmont to Altamont

(2620 feet above tide and the greatest elevation along the route)

the road constantly and almost insensibly ascends, in every portion

filling the mind with a sense of as perfect security as if the

transit were made, in a coach.

At Altamont we dipped over the eastern edge of the Alleghanies,

and by a slight descent entered the highland basin of the old

mountain lakes, which extends over many thousands acres, and is

known as the "Glades." There the Youghiogheny takes

its rise, while the dividing ridge of the great Backbone sends

the water on one side into the Gulf of Mexico, and on the other

into  the Chesapeake.

These beautiful glades, or mountain meadows, are not connected

in a level field like our western prairies, but lie in broken

outlines, with small wooded ranges between them or jutting out

from their midst in moderate elevations. At this height the air

is extremely rarified and cool throughout summer; so that, although

the country is not adapted for agriculture, it is calculated for

every species of animal and vegetable life that is disposed to

run wild and take the world as it finds it. It is rich in all

the natural grasses that delight a herdsman, relieved by islands

of white-oak interspersed with alder; it is full of copious streams,

kept full and fresh by the clouds that condense round the summits;

its waters are alive with trout, and waste themselves in deep

cascades and falls after furnishing pools for the fish; it pastures

innumerable herds of sheep, whose tenderness and flavor rival

that of the deer which abound in the woods; wild turkeys and pheasants

hide among its oaks, beeches, walnuts, and magnolias; the sugar

maple supplies it with a tropical luxury in abundance; the woods

are vocal with larks, thrushes, and mocking-birds; and in the

flowering season nothing is gayer than the meadows with their

showy flowers.

the Chesapeake.

These beautiful glades, or mountain meadows, are not connected

in a level field like our western prairies, but lie in broken

outlines, with small wooded ranges between them or jutting out

from their midst in moderate elevations. At this height the air

is extremely rarified and cool throughout summer; so that, although

the country is not adapted for agriculture, it is calculated for

every species of animal and vegetable life that is disposed to

run wild and take the world as it finds it. It is rich in all

the natural grasses that delight a herdsman, relieved by islands

of white-oak interspersed with alder; it is full of copious streams,

kept full and fresh by the clouds that condense round the summits;

its waters are alive with trout, and waste themselves in deep

cascades and falls after furnishing pools for the fish; it pastures

innumerable herds of sheep, whose tenderness and flavor rival

that of the deer which abound in the woods; wild turkeys and pheasants

hide among its oaks, beeches, walnuts, and magnolias; the sugar

maple supplies it with a tropical luxury in abundance; the woods

are vocal with larks, thrushes, and mocking-birds; and in the

flowering season nothing is gayer than the meadows with their

showy flowers.

A little village is growing up at Oakland in the midst of these

glades, as a sort of nestling-place for folks who are willing

to be satisfied by being cool, quiet, and natural during summer.

We halted there for the night, and were not reluctant to ensconce

ourselves beneath blankets even in the "leafy month of June."

In order to

make a new resort popular, it is necessary, as the world goes,

to have the lead of a fashionable belle or the command of a fashionable

doctor. Nature, of itself, is not sufficiently attractive for

artificial society; so that one must either be ill or be led, in order to adopt what is really good, and surround

it with allurements of French cookery, fast horses, a band of

music, and weekly balls. It was many years before Saratoga and

Newport ripened from a simple well and a wild sea-shore into the

luxuriant style of Bath and Brighton. Yet I do not despair of

seeing the day when the Maryland Glades, the head-waters of Potomac

and Cheat, and the romantic cascades of the neighboring Blackwater

will be crowded with health-hunters. The turn of Nature to be

in fashion again must come round; for when invention exhausts

the artificial (and the age of hoops seems verging on that desirable

end), there is no resource but simplicity. There are numbers of

reasonable people who must be eager to quit the beaten paths,

and escape to spots where they will not be stifled by society:

and these glades and mountain streams, with their constant coolness

and verdure, are precisely the places for them. For several years,

many of our Maryland and Virginian sportsmen have been fishing

the streams; beating up the deer, pheasants, and wild turkeys;

driving over the fine upland roads; drinking the pure water; exercising

robustly for a month or more; sleeping soundly every night of

July and August, and getting back to their work in the fall, as

hearty as the "bucks" they made war on in the mountains.

In order to

make a new resort popular, it is necessary, as the world goes,

to have the lead of a fashionable belle or the command of a fashionable

doctor. Nature, of itself, is not sufficiently attractive for

artificial society; so that one must either be ill or be led, in order to adopt what is really good, and surround

it with allurements of French cookery, fast horses, a band of

music, and weekly balls. It was many years before Saratoga and

Newport ripened from a simple well and a wild sea-shore into the

luxuriant style of Bath and Brighton. Yet I do not despair of

seeing the day when the Maryland Glades, the head-waters of Potomac

and Cheat, and the romantic cascades of the neighboring Blackwater

will be crowded with health-hunters. The turn of Nature to be

in fashion again must come round; for when invention exhausts

the artificial (and the age of hoops seems verging on that desirable

end), there is no resource but simplicity. There are numbers of

reasonable people who must be eager to quit the beaten paths,

and escape to spots where they will not be stifled by society:

and these glades and mountain streams, with their constant coolness

and verdure, are precisely the places for them. For several years,

many of our Maryland and Virginian sportsmen have been fishing

the streams; beating up the deer, pheasants, and wild turkeys;

driving over the fine upland roads; drinking the pure water; exercising

robustly for a month or more; sleeping soundly every night of

July and August, and getting back to their work in the fall, as

hearty as the "bucks" they made war on in the mountains.

Let me recommend Oakland to a cook who wishes to make a reputation

on venison and trout, and to a belle who is brave enough to

bring Nature into fashion!

We slept at

Oakland. The mists hung low over these highlands long after sunrise,

and the air was so bracing that we found overcoats necessary as

we bowled across the great Youghiogheny, on a single arch of timber

and iron, and passed the picturesque Falls of Snowy Creek, where

the road quits the prairie and strikes a glen through which the

stream brawls in foam, contrasting bravely with the hemlocks and

laurels that line the pass.

We slept at

Oakland. The mists hung low over these highlands long after sunrise,

and the air was so bracing that we found overcoats necessary as

we bowled across the great Youghiogheny, on a single arch of timber

and iron, and passed the picturesque Falls of Snowy Creek, where

the road quits the prairie and strikes a glen through which the

stream brawls in foam, contrasting bravely with the hemlocks and

laurels that line the pass.

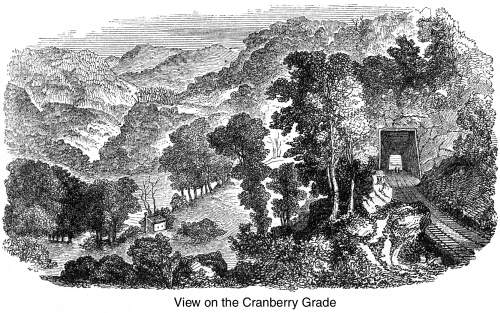

At Cranberry Summit the mountain-levels and glade-lands terminate,

at an elevation of 2550 feet above tide, and only 76 feet lower

than Altamont, where we entered the field, twenty miles back.

From this elevated point we catch the first grand glimpse of

the "Western World," in along gradual sweep down the

Alleghanies toward the affluents of the Ohio. The descent begins

instantly, along the slopes of Saltlick Creek, through a mass

of excavations, two tunnels, and fifty feet of viaduct. Downward

and downward we swept as comfortably as on a plain, till an easy

and almost imperceptible descent of twelve miles, through a forest

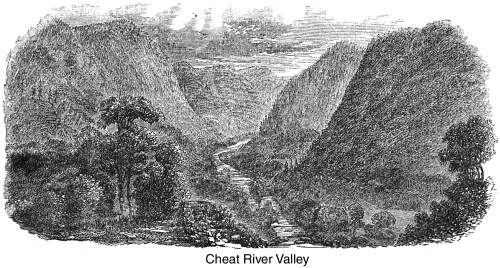

of firs and pines, brought us to the dark waters of Cheat River.

After the difficulties of ascending, crossing the Backbone of

the Alleghany, and descending its first western slope-all of which,

like Columbus's discovery, "seem so easy" now that they

are overcome—a new marvel has been accomplished in the preservation

of a high level by massive viaducts and by boring the mountains

with tunnels. On Cheat River,  at the bottom of this descent, we approached the first

of these marvels, two noble arches of iron, firm and substantial

as the mountains they join. Then comes the ascent of Cheat River

Hill. Next are the slopes of Laurel and its spurs, with the river

on the right; till the dell of Kyer's Run is passed on an embankment,

and Buckeye Hollow crossed on a solid work whose foundations are

laid deeply below the level of the road. Both of these splendid

structures have walls of masonry, built of the adjacent rock.

at the bottom of this descent, we approached the first

of these marvels, two noble arches of iron, firm and substantial

as the mountains they join. Then comes the ascent of Cheat River

Hill. Next are the slopes of Laurel and its spurs, with the river

on the right; till the dell of Kyer's Run is passed on an embankment,

and Buckeye Hollow crossed on a solid work whose foundations are

laid deeply below the level of the road. Both of these splendid

structures have walls of masonry, built of the adjacent rock.

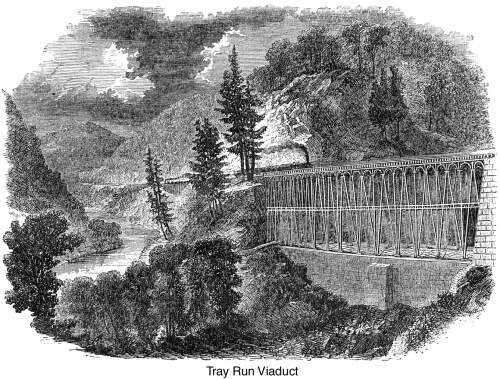

Beyond this we reach Tray Run, which is passed by an iron viaduct,

six hundred feet in length, founded on a massive base of masonry

as Arm as the mountain itself. All these remarkable works—chiefly

designed by Mr. Fink—have borne the trial of heat and frost,

travel and transportation, for several years; and when closely

inspected, their immense solidity, security, and strength, are

as easily tested by the eye as they have been by use and time.

These beautiful

structures had hardly been passed when we wound upward across

Buckthorne Branch, and half a mile further, left the declivities

of Cheat River, with its brown waters dyed by the roots of laurel

and hemlock, and bordered by the bright flowers of the rhododendron.

Our last glimpse of this mountain river was through a tall arch

of forest, rounding off, far below, in its dark valley of uninhabited

wilderness.

These beautiful

structures had hardly been passed when we wound upward across

Buckthorne Branch, and half a mile further, left the declivities

of Cheat River, with its brown waters dyed by the roots of laurel

and hemlock, and bordered by the bright flowers of the rhododendron.

Our last glimpse of this mountain river was through a tall arch

of forest, rounding off, far below, in its dark valley of uninhabited

wilderness.

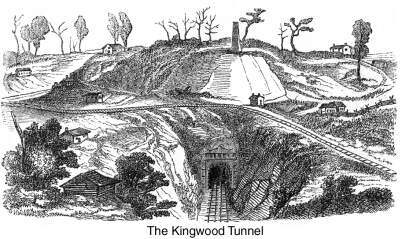

Beyond Cassidy's Ridge we encountered another, and perhaps

the most remarkable of these gigantic works. The road can only

escape from its mountain-prison by bursting the wall. Up hill

and down hill, through brake and ravine, it has cleft its way

from Piedmont, like a prisoner seeking release from his bars,

till at last it finds a bold barrier of 220 feet abruptly opposed

to its departure! For a while (before the entire completion of

the road) engineering skill led a track over this steep by

an ascent of 500 feet in a mile; but finally the giant has

been subdued, and the last great wall of the Alleghanies passed

by piercing the mountain. For nearly three years crowds of laborers

were engaged in blasting through solid rock the 4100 feet of the

Kingwood Tunnel, and a year and a half more was spent in shielding

it with iron and brick, so as to make its walls more solid, if

possible, than the original hills.

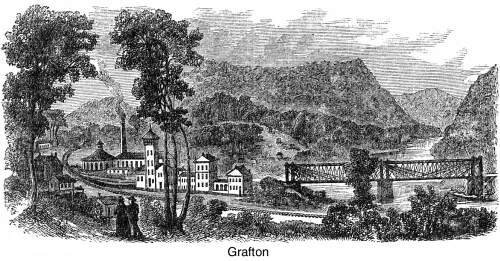

For five miles

from the western end of this tunnel we descended to the broader

valleys about Raccoon Creek, and gliding through another tunnel

of 250 feet, followed the water till we entered the Tygart River

Valley, at Grafton, where the Northwestern Railway diverges to

Parkersburg, on the Ohio, ninety-five miles below Wheeling. The

establishments of the Company at this point are erected in the

most substantial way for the comfort and security of all who may

visit this interesting region.

For five miles

from the western end of this tunnel we descended to the broader

valleys about Raccoon Creek, and gliding through another tunnel

of 250 feet, followed the water till we entered the Tygart River

Valley, at Grafton, where the Northwestern Railway diverges to

Parkersburg, on the Ohio, ninety-five miles below Wheeling. The

establishments of the Company at this point are erected in the

most substantial way for the comfort and security of all who may

visit this interesting region.

There are few routes of travel in America—and none, probably,

by rail—worthier of attention than the region between the

slopes of the western glade-land to the mountain exit at Kingwood.

It is all absolute mountain, absolute forest, absolute solitude.

In winter it is the very soul of desolation, when the trees are

iced, like huge stalactites, from top to bottom, and the ravines

among the cliffs blocked with drifted snow. But in spring or summer

it presents splendid bits of forest scenery. The glens are narrow,

and there are few distant prospects; but there is every where

the same ragged gloom—the same overarching hemlocks and firs—the

same torrent roar, foaming over rocky beds—the same fringing

of thick-leaved laurel—the same oozy plashes of morass, rank

with dark vegetation—the same black mountain-face—the

same absence of people and farms—the same sense of absolute

solitude.

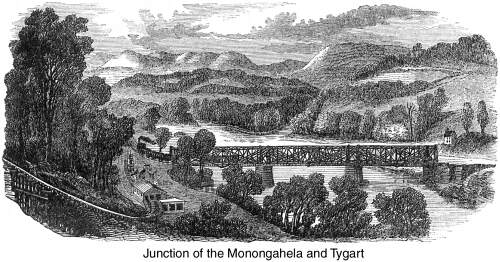

But in Tygart's Valley the landscape softens and becomes more

human, with the marks of agriculture and habitation, and the road

seems to bound along more gayly, as if exulting in its release

from the mountain. The river winds gently through rounder and

lower hills and broader meadows, broken only by "the Falls,"

which, in a few steep pitches, tumble seventy feet in the distance

of a mile. Not far from this point Tygart River and the West Fork

unite to form the Monongahela, which, a quarter of a mile below

the junction, is crossed by an iron viaduct 650 feet long—the

largest iron bridge, in America, and due to the engineering skill

of Mr. Fink.

In these central

solitudes every thing seems to be the property of the wilderness—a

wilderness incapable of yielding to any mastery but that of an

engineer; and it may fairly become a matter of national pride

that scientific men were found in our country bold enough to venture

on grades by which any mountain may be passed. Where ground was

wanted, Nature seemed to have scooped it away; where it was not

wanted Nature seemed to have stacked it up for future purposes.

There are considerable difficulties between Baltimore and Cumberland;

yet, in a country which rises only 639 feet above tide in 179

miles, a road may be constructed by ordinary perseverance and

skill. But they who desire to understand the power of science

in conquering nature by steam and iron must climb and cross the

Alleghanies between Piedmont and Kingwood. The success of this,

the most difficult portion of the enterprise, is due to the engineering

of Mr. Latrobe and the financial energy of Mr. Swann.

In these central

solitudes every thing seems to be the property of the wilderness—a

wilderness incapable of yielding to any mastery but that of an

engineer; and it may fairly become a matter of national pride

that scientific men were found in our country bold enough to venture

on grades by which any mountain may be passed. Where ground was

wanted, Nature seemed to have scooped it away; where it was not

wanted Nature seemed to have stacked it up for future purposes.

There are considerable difficulties between Baltimore and Cumberland;

yet, in a country which rises only 639 feet above tide in 179

miles, a road may be constructed by ordinary perseverance and

skill. But they who desire to understand the power of science

in conquering nature by steam and iron must climb and cross the

Alleghanies between Piedmont and Kingwood. The success of this,

the most difficult portion of the enterprise, is due to the engineering

of Mr. Latrobe and the financial energy of Mr. Swann.

As the pioneer of such internal improvements in the Union,

it has been the school for subsequent railways, and deserves the

gratitude of scientific men for true principles of location and

construction. The bridging and tunneling alone, along the whole

route, amount to about five and a quarter miles; the laborers

and employees form almost five regiments in number; and, when

we take into consideration the depots, tanks, engines, rails,

station-houses, and innumerable cars for freight and travel, as

well as the two lines of telegraphic wires belonging exclusively

to the Company, which keep every portion in communication and

successful operation throughout the line, one no longer wonders

that twenty-five millions were, expended on the structure, but

is only surprised that the people of a small, single State could

accomplish so colossal an enterprise.

The remaining eighty or ninety miles between the junction of

the Tygart and Monongahela. rivers and the Ohio are full of rich

points of scenery, and contain some fine works. There are several

bridges of note, a tunnel of 2350 feet at Board-tree, and another

of 1250 feet in the ridge separating Fish Creek from Grave Creek.

The country is comparatively new, and the impetus given to

it by this improvement may be seen in the settlements along the

route that sprang up during its construction, most of which have

expanded into villages and become the centres of trade and agriculture.

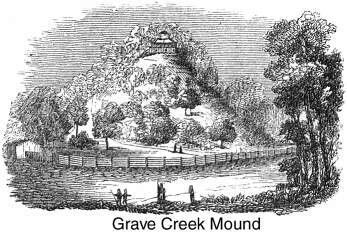

We slept in

the cars on a "siding," near Cameron, about seventeen

miles from the Ohio, and when we woke next morning found that

our engineers and conductors had moved so silently from our resting-place

that we had been transferred insensibly to Moundville, on the

bank of the river. We had determined to stop here to inspect the

celebrated Grave Creek Mound; and, as the sun rose, passed through

the village, finding our way to the remains of this Indian monument.

"It is one of the largest," say Squier and Davis, "in

the Ohio Valley, measuring about seventy feet in height, by one

thousand in circumference at the base." It was excavated

in 1838 by sinking a shaft from its crown to its base, intersected

by a horizontal drift midway between them. Two sepulchral chambers

were found within—one at the base and the other thirty feet

above it, the lower containing two skeletons, the upper but one.

With these remains were found several thousand shell-beads, a

number of ornaments of mica, copper bracelets, and various articles

of carved stone. At the time of these discoveries the owner of

the mound built the wooden structure seen on the apex in the cut,

and used it as a sort of museum for the preservation of the relics.

But the structure is now open to the elements as well as visitors,

and is rapidly decaying; the Indian remains and ornaments have

been dispersed, and nothing is left but the gigantic tumulus and

the ancient trees that overshadow it.

We slept in

the cars on a "siding," near Cameron, about seventeen

miles from the Ohio, and when we woke next morning found that

our engineers and conductors had moved so silently from our resting-place

that we had been transferred insensibly to Moundville, on the

bank of the river. We had determined to stop here to inspect the

celebrated Grave Creek Mound; and, as the sun rose, passed through

the village, finding our way to the remains of this Indian monument.

"It is one of the largest," say Squier and Davis, "in

the Ohio Valley, measuring about seventy feet in height, by one

thousand in circumference at the base." It was excavated

in 1838 by sinking a shaft from its crown to its base, intersected

by a horizontal drift midway between them. Two sepulchral chambers

were found within—one at the base and the other thirty feet

above it, the lower containing two skeletons, the upper but one.

With these remains were found several thousand shell-beads, a

number of ornaments of mica, copper bracelets, and various articles

of carved stone. At the time of these discoveries the owner of

the mound built the wooden structure seen on the apex in the cut,

and used it as a sort of museum for the preservation of the relics.