THE GRANITE TURNPIKE

The Turnpikes of New England—by

Frederic J. Wood—1919

The granite quarries of Quincy first came prominently before

the country when it was decided to construct the Bunker Hill Monument

from their product. They were four miles from tidewater, and the

only means of transporting the blocks of stone was over the roads

of that period, of which but a few miles tributary to the quarries

were turnpikes. To reach Boston required a roundabout journey

either by way of the Neponset Bridge or by way of Milton Lower

Mills, and there was no satisfactory way of reaching Charlestown,

where the monument was to be built. Hence a railway was conceived

by which the stones were carried down hill to the tidewater of

the Neponset River at Gulliver's Creek, where they were loaded

on to barges which were floated around to the dock in Charlestown.

This served very well as long as the stones were wanted at points

accessible by water, but an early demand arose for building stone

to be used in the new parts of Boston; and a more direct route

was needed.

April 13, 1837, the, proprietors of the Granite Bridge were

incorporated for the purpose of building a road from the old county

road at or near the store of I. Babcock, Jr., in Milton and running

thence north ten and three quarters degrees west, about two hundred

and seventy-two rods; north nineteen degrees west, about fifty-six

rods; north twentyfive and one half degrees west, about one hundred

and twenty-eight rods to the Neponset River, "and to locate,

build, and construct a bridge across said river in continuation

of said last-mentioned line of said road to Dorchester";

and thence to continue the road north eight and three quarters

degrees west, about one hundred and eight rods to the "lower

road" in Dorchester on or near the land of Rev. Ephraim Randall.

A draw not less than thirty-one feet wide was to be located by

commissioners appointed for that purpose, and wharves or piers

seventy-five feet long were to be built on each side to assist

vessels in passing through the opening. The total cost of bridge

and road was not to be in excess of fifteen thousand dollars and

the management was not allowed to incur annual expenses of over

fifteen hundred dollars.

Plotting the description of the route of the road plainly shows

that it began in the center of East Milton Village adjacent to

the crossing of the Granite Railway by Adams Street, the old county

road and the old colonial road to Plymouth. Thence it marked out

the lines of the present-day Granite Avenue across the marshes

and river to Adams Street in Dorchester, the "lower road."

This "lower road" was an ancient institution at that

date, having been an alternate route by which the bridge over

the Neponset at Milton Lower Mills was reached from Boston, the

other road passing through Grove Hall and following the Washington

Street of to-day. The "lower road" commenced at the

corner of Washington and Eustis streets near the boundary at that

date between Boston and Roxbury, and followed over what are now

known as Eustis, Mall, Dearborn, Dudley, Stoughton, Pleasant,

Bowdoin, Adams, and Washington streets to Milton Lower Mills.

At its beginning is found one of the oldest cemeteries in New

England, interments having begun there in 1633 and continued until

1854. At that point, also, was the first barricade erected by

the Americans to prevent the British troops from making a sortie

during the siege of Boston.

As the road built by the bridge company commenced almost on

the location of the Granite Railway and was only a few hundred

feet away from it at the railway's terminus, it may not be amiss

to consider here the cars and track which became so familiar to

the turnpike workmen. When the bridge and turnpike were built

the Granite Railway had been in operation about eleven years and

the railroads from Boston to Providence, Worcester, and. Lowell

about two years.

The track of the Granite Railway was originally composed of

stone crossties bedded in the ground at intervals of eight feet

with wooden rails faced with a bar of iron on which the wheels

ran. By 1837 the wooden rails had been replaced with stringers

of granite hammered smooth on the upper face and having similar

bars of iron pinned to their tops. It was officially stated that

the maintenance costs on this form of track had not amounted to

ten dollars a year, and the track continued in use until 1871,

when it was sold to the Old Colony Railroad Company and replaced

by a modern railroad construction. The first car had wheels six

and a half feet in diameter with the load carried on a platform

running just clear of the rails and hung from the axles by chains.

The capacity was about six tons.

In 1846 the Granite Railway Company was authorized to extend

its road, crossing the Neponset River not over five hundred feet

below the Granite toll bridge and uniting with the newly chartered

Dorchester and Milton Branch Railroad in Dorchester. It was also

given authority to sell its road to the Old Colony Railroad Company,

a privilege which was renewed in 1848 but which was not utilized

until 1871. Then the Old Colony introduced a curve in the track

at the foot of the hill on the edge of the marshes and carried

the track easterly along the southerly bank of the river to a

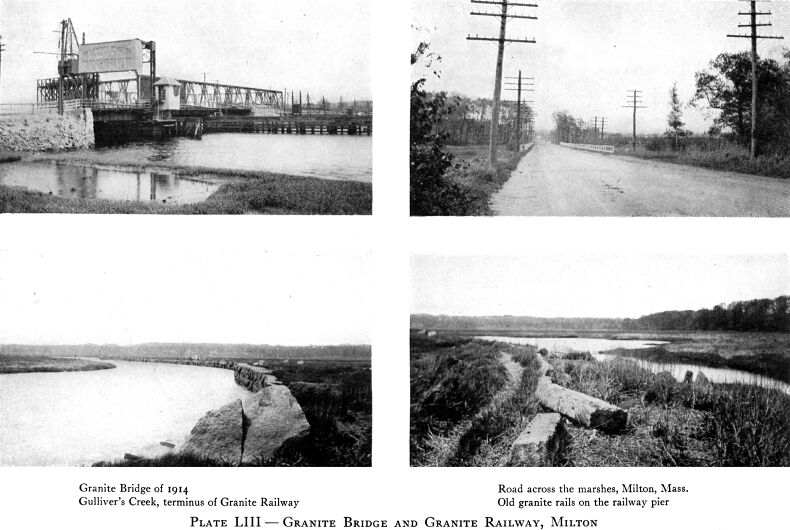

junction with its main line at Atlantic. The section running out

over the marsh and the pier at Gulliver's Creek were thus left

out of the reckoning, but the pier is still to be plainly traced,

and on it can be seen to-day about two hundred feet of the old

granite rails still in the place where they carried the cars of

stone. The iron plates which received the tread of the wheels

are gone but rust clearly shows where they were, and the pins

which held them are yet in place.

It would seem that the drivers of teams which passed over the

Granite Bridge were not satisfied with the capacity of the railway

car, for the company was obliged to ask the passage of an act

in 1845 by which the owner of a load of over seven tons was made

liable for any damage done to the bridge.

With Yankee shrewdness the company reported the bridge and

road as costing fifteen thousand dollars, all that the law allowed,

which does not seem to have been an unreasonable figure. There

was considerable difficult construction of the road across the

soft marsh and the bridge abutments must have been costly to build.

The corporation made returns of business from 1840 to 1854, but

complete for only eleven years. For those years the net earnings

were about three hundred and seventeen dollars on an average,

or two and eleven hundredths per cent. The gross receipts ran

from five hundred and fifty to fifteen hundred dollars, but generally

around seven or eight hundred. In one year only, 1852, was a loss

reported when the business ran behind to the amount of three hundred

and sixty-three dollars.

May 4, 1865, the Norfolk county commissioners were authorized

to lay out the bridge and road as a public highway. The property

had fallen into a bad condition and the commissioners were required

to put the same into proper repair, after which the towns of Dorchester

and Milton were to assume the maintenance. The commissioners,

under that authority, laid out the road and bridge September 8,

1865.

The present bridge was in part built under the provisions of

an act passed June 13, 1913, by which a commission was provided

for the purpose of constructing a new bridge with suitable approaches,

substantially replacing the old bridge. Seventy thousand dollars

was to be advanced by the Commonwealth to be repaid later by Suffolk

and Norfolk counties, Milton, and Quincy. The control is now vested

in the mayor of Boston and the chairman of the selectmen of Milton.

We have previously noted the effort to build a road by the

Tyringham and Sandisfield Turnpike Corporation and concluded that

the effort was in vain. In 1841, February 27, the Clam River Turnpike

Corporation was formed to carry out the same purpose. The route

allowed this company was from New Boston in Sandisfield to Hubbard's

cider mill in Tyringham, following up the Clam River and down

Hop Brook. At the date of this charter there were several railroads

actually built and in operation in Massachusetts, and the builders

of the Western Railroad were then cleaving the Berkshires. The

day of the turnpike had passed with the demonstration of the success

of the locomotive, and this corporation was born too late. Not

even a location by a committee of the court was secured and the

whole enterprise faded away.

That there was some need of a road in the route specified is

evident from the fact that the local authorities later did build

a public road between West Otis and Tryingham on the line allowed

the Clam River Corporation.

Twenty-seven years later, March 23, 1868, the Chelsea Beach

and Saugus Bridge and Turnpike Company was incorporated, the last

in Massachusetts. Its proposed road was to lead from the Ocean

House in North Chelsea, now Revere, to the Salem Turnpike in Saugus

opposite the junction with the Saugus Road. Apparently this road

was to be about a mile long, starting at the outer end of the

Point of Pines, and running straight, as was a turnpike's wont,

across the marshes to the Salem Turnpike near the Saugus and Lynn

boundary. It does not appear that anything beyond securing the

charter was ever done.

Although the turnpike era was long past, this corporation does

not altogether stand alone. Its purpose plainly was to give entrance

to a pleasure resort, and many similar turnpike charters are found

on the New Hampshire legislative records at the same and later

dates, providing for roads to the summits of several of the noted

mountains of that state.

This page originally appeared on Thomas Ehrenreich's Railroad Extra Website