The Early Railroads

From New Jersey as a Colony and a State

by Francis Bazley Lee—1902

OF THE many contests, industrial, religious, and political,

of which New Jersey has been the scene no one struggle for supremacy

was waged with greater bitterness than the fight for existence

between the advocates of a railroad connecting New York and Philadelphia

and the proprietors of the stage-coach lines, who then controlled

the transportation of freight and passengers across the State.

With the advancement, of the plan for a railroad there was

a vigorous cry of "monopoly," a cry by no means unusual,

in view of the fact that no greater monopoly ever existed than

that exercised by the stage-coach proprietors. As late as 1834

the rate of stage-coach fare between Philadelphia and New York

was six dollars, the time occupied in the journey being an entire

day. By control of the inns and taverns on the route, and a system

of practically compulsory "tips" for employees, to which

must be added many discomforts, the travelling public was at the

mercy of the stage lines, except the few voyagers who "snubbed"

across New Jersey by way of the canal.

Under these conditions the Camden and Amboy Railroad came into

being.

In the contention that the Camden and Amboy Railroad was a

"monopoly" there was nothing new. As early as 1707 the

Assembly complained "that patents had been granted to one

Dellman to transport goods on the road from Amboy to Burlington

for a number of years to the exclusion of others," and that

such executive action was "destructive to that freedom which

trade and commerce ought to have." To this Governor Cornbury

replied that, by reason of the monopoly, goods could be sent across

New Jersey once during a fortnight "without danger of imposition,"

for that alone by means of Dellman's stage wagon a trade had been

carried on between Philadelphia, Burlington, Amboy, and New York

"which was never known before, and which, in all probability,

never would have been." When came the later stage-boat lines,

those under the management of the Bordens, Richardson, and O'Bryant,

the ferries of the Inians, Billops, and Redfords in East Jersey,

there was still the complaint of monopoly, excessive rates, and

poor service.

By the opening of the nineteenth century the roads of New Jersey

between Philadelphia and New York were but little improved beyond

the deplorable condition which Governor Franklin criticised in

1768, when he said that these highways were "seldom passable

without danger and difficulty." But with the agitation concerning

internal improvements which marked the advent of Jefferson's administration

no less than nine turnpikes were chartered by the Legislature

on the route from Philadelphia to New York. These were the Hackensack

and Hoboken, 1802; the Trenton and New Brunswick, 1804, with its

annex, the bridge over the Delaware; the Jersey City and Hackensack,

1804; the Essex and Middlesex from New Brunswick to Newark, 1806;

a continuation of the Trenton and New Brunswick turnpike from

Princeton to Kingston, 1807; the Woodbridge and Rahway, 1808;

and a branch of the Trenton and New Brunswick from Burlington

through Bordentown to Trenton, 1808. It was not, however, until

1816 that the famous Bordentown and South Amboy turnpike was constructed.

It is with a great degree of justice that J. Elfreth Watkins,

Sr., of Washington, D. C., in his admirable monograph dealing

with the origin and, early history of the Camden and Amboy Railroad,

attributes the progress of steam transportation on the soil and

waters of the State of New Jersey to the efforts of John Stevens.

In that long life between 1749 and 1838 this inventor-statesman

saw New Jersey emerge from the horrors of the French and Indian

War, witnessed, as treasurer of New Jersey during the Revolution,

the political birth of a nation, and helped, more than any other

man, to lay the foundations of that system of transportation which

has made the State the terminus in whole or in part of every great

trunk line or its allied interests in the republic. Ceaselessly

active, he devoted the ninety years of his life to the common

good, as an experimentalist and inventor, giving to the improvement

of steam navigation a large proportion of that great wealth which

he had inherited and increased.

There hangs in the section of transportation and engineering

in the United States National Museum in Washington a medallion

portrait of John Stevens, and beneath it an inscription. This

is but a small part of the record of so useful a life, but from

it there may be learned that John Stevens, as a petitioner, was

the father of the patent law of 1790, that he, in 1792, took out

patents for propelling vessels by steam pumps, modified from Savary's

plans, and that in his experiments on different modes of propulsion

by steam he had as his associates Brunel, constructor of the Thames

Tunnel connecting London with the Surrey shore; Chancellor of

the State of New York Robert R. Livingston, whose sister Stevens

married; and Nicholas I. Roosevelt, of the patroon family of which

President Theodore Roosevelt is a member. From these experiments,

in 1798, John Stevens made a steamboat that navigated the Hudson.

In 1804 he made his first application of steam to the four-bladed

screw propeller, which has survived many forms and which was not

commercially successful until 1840. His multi-tubular boiler appeared

in 1803, and the first steam ferry in the world, that between

New York and Hoboken, was opened October 11, 1811, with the trip

of the "Juliana."

Turning his attention during the second war with England to

the possibilities of steam transportation upon land, he urged

the construction of a steam road instead of the Erie Canal, and

paved the way for the building of those local railroads which

were subsequently united in the New York Central Railroad system.

Later, in 1823, with Horace Binney and Stephen Girard, John Stevens

obtained a charter from the State of Pennsylvania for a railroad

from Lancaster to Philadelphia, on the line of the Pennsylvania

Railroad, and in 1826 he built the first locomotive having a tubular

boiler which ran upon any railroad in America. This locomotive

carried six people at a speed of over twelve miles an hour, and

was operated upon a circular track within the limits of his estate

in Hoboken.

The immediate predecessor of the Camden and Amboy Railroad

was the Union Line of wagons and stages, which enjoyed a monopoly

of the trade between New York and Philadelphia. As early as 1808

the "Phoenix," which was, according to Mr. Watkins's

narrative, " the first steam driven craft to venture out

to sea," was designed by John Stevens, built by Robert L.

Stevens, and was taken to Philadelphia from Hoboken by the Sandy

Hook-Cape May route. The "Phoenix" became the property

of the Union Line, whose route of one hundred and one miles between

Philadelphia and New York was divided into three sections—by

steamboat from Philadelphia to Trenton, by wagon or stage upon

the Trenton-New Brunswick turnpike, and thence by the Raritan

and the waters bounding Staten Island on the west to New York.

The trip occupied from noon of one day until the morning of the

next, and was both tedious and expensive.

It was given to John Stevens to look far into the future, to

see that even the steamboat and the canal projects in Europe were

to be supplanted. As early as 1812 Stevens had published his "Documents

Tending to Prove the Superior Advantages of Railways and Steam

Carriages Over Canal Navigation," but even his valid reasoning,

his logical conclusions, based upon a wealth of facts and figures,

failed to convince capitalists that railroads were more beneficial

than canals, and that as investments they might become reasonably

popular.

In the meantime the growing commercial importance of England,

and the congestion of her population in the manufacturing centers,

had developed railroad construction to a degree that attracted

the attention of the civilized world. Among those who went abroad

for a personal study of English railroads was William Strickland,

a member of the Pennsylvania Society for Internal Improvement,

and it was the facts presented in this report, and the personal

enthusiasm of John Stevens and his friends, that led to the first

public railroad meeting ever held in the commonwealth. Upon the

14th of January, 1828, "a large and respectable meeting of

the citizens of New Jersey friendly to the proposed railway from

Camden to Amboy" occupied the court house in Mount Holly.

Of this assemblage John Black was president, John Dobbins vice-president,

and Charles Stokes and James Newbold secretaries. A committee

appointed to draft resolutions expressive of the sense of the

meeting reported that the members were deeply impressed with the

importance of internal communication, and recommended the extension

of the policy throughout the Atlantic States, that New Jersey

should sustain a line of communication between New York and Philadelphia,

and that the application to the Legislature for the railroad is

highly approved, not only as a local project, but as one of the

most important links in the great chain of " internal intercourse."

A general committee to urge internal intercourse." A general

committee to urge the matter before the House of Assembly and

Council, and committees from Gloucester and Burlington Counties

to secure signatures upon a legislative memorial, were selected.

This meeting was followed by others at Burlington, Bordentown,

Princeton, and Trenton, as well as in other portions of the State,

upon which occasions similar sentiments were expressed, while

the Legislature received memorials in 1828-29 and in 1829-30 upon

this subject.

But the friends of the canal interests were by no means inactive.

The Union Line had identified its powerful interests with those

of the projected railroad as against the canal scheme, which had

been taken up by the People's Line and lesser rivals of the Union

Line. The State was filled with talk of "monopoly,"

of the injury that would come to stage drivers, tavern keepers,

and road gangs, of the political dangers that a railroad charter

presented, and, above all, that the railroad itself was destructive

to life and limb, brought undesirable elements to the State, endangering

public morals, and was in every way objectionable. Then appeared

in the legislative session of 1829-30 the first "lobby,"

recognized as such, when the friends of the railroad and the canal

found it necessary, as in the latter sixties and early seventies,

when the "monopoly" agitation again appeared, to go

armed about the streets of Trenton.

But in January, 1830, a compromise was effected. From negotiations

completed between the principals of the warring interests charters

were granted the Camden and Amboy Railroad and Transportation

Company and the Delaware and Raritan Canal Company. The separate

legislation was passed upon the 4th of February, 1830. On the

28th of April, 1830, the organization of the Camden and Amboy

Railroad was effected, in Camden, by the election of Robert L.

Stevens, of Hoboken, president; Edwin A. Stevens, of Hoboken,

treasurer; Jeremiah H. Sloan, of Camden, secretary; and a board

of directors consisting of Abraham Brown, of Mount Holly; William

McKnight, of Bordentown; William I. Watson, of Philadelphia, and

Benjamin Fish, of Trenton.

Under the provisions of the Camden and Amboy Company's charter

the capital stock authorized was one million dollars, divided

into shares of one hundred dollars each, with the privilege of

increase to one million five hundred thousand dollars. The Legislature

reserved the right to subscribe to one-quarter of the stock. The

designated terminals were indefinite. On the south the road was

to commence at some point between "Cooper's and Newton's

Creeks," and on the north to end at "some point on the

Raritan Bay."

There first appeared in the charter that provision against

which all subsequent attacks of the "anti-monopolists"

were directed. In lieu of all taxes the new railroad company agreed

to pay a transit duty of ten cents for each passenger and fifteen

cents a ton for all merchandise transported. These transit duties

were to cease in case the Legislature authorized the construction

"of any other road to transport passengers from Philadelphia

to New York to terminate within three miles of the commencement

or termination of this road."This protection was made absolute

upon March 15, 1832, when the Legislature in an amendment to the

statute provided that during the life of the charter—the

State having reserved the right to purchase the road at the end

of thirty years—it should be unlawful to construct any railroad

between Philadelphia and New York without the consent of the companies.

Throughout the spring and summer of 1830 surveys were made

under the direction of Major John Wilson, of the United States

army, assisted by Lieutenant William Cook, having charge of the

section from South Amboy to Bordentown, and John Edgar Thompson,

afterward president of the Pennsylvania Railroad Company, in charge

from Bordentown to Camden.

With the completion of the surveys for the Camden and Amboy

Railroad Robert L. Stevens started upon a mission to England,

under instructions to order a locomotive and rails for the new

road. Fortunately for the cause of transportation the long voyage

gave Stevens an opportunity to exercise his talents as an inventor.

While upon the ship he either produced or perfected the American

or Stevens rail, adding a base to the "T" rail,

and dispensing with the chair then in use. To this he added the

"hook headed" spike, the "iron tongue," known

in its present form as the "fish bar," and the rivets

(now bolts and nuts), necessary to complete the joints. After

many failures the Guest Iron Works at Dowlais, Wales, succeeded

in making a rail sixteen feet in length and weighing about forty

pounds to the yard. Between May, 1831, and October, 1832, there

were twenty-three shipments of rails to New Jersey, the first

arriving on the ship "Charlemagne," and laid on the

piece of track near Bordentown in August, 1831. At this spot,

upon November 12, 1891, the Pennsylvania Railroad Company erected

a handsome monument, properly inscribed, commemorating the sixtieth

anniversary of the first movement by steam upon a railway in the

State of New Jersey.

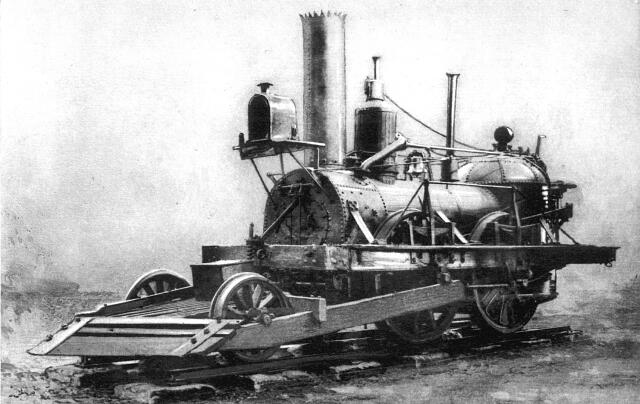

The village of Bordentown, upon a sultry day in the middle

of August, 1831, was all excitement, for there stood upon the

wharf, surrounded by a crowd of the curious, the locomotive "John

Bull " or "No. 1," which had been recently completed

at the English works of Stephenson and Company. To Isaac Dripps,

later master mechanic of the Camden and Amboy Railroad, whose technical education

had been acquired with the Stevenses in their experiments with

steamboats on the Delaware and the Hudson, was assigned the duty

of assembling the parts of the "John Bull." Without

directions or drawings, Dripps, who had never seen a locomotive,

prepared the engine, weighing ten tons, for track work. A tender

was made from a converted four-wheel flat car, used by the contractors,

the tank being a large whiskey barrel, and the supply of water

conveyed to the boiler by short sections of shoe leather hose

made by a Bordentown shoemaker. After a preliminary test the locomotive

was given a public trial upon the 12th of November, 1831, in the

presence of the members of the Legislature and invited guests

of prominence. Attached to the locomotive were two four-wheeled

coaches, built to be drawn by horses if need should arise. These

coaches were practically carriage bodies, three doors to a side,

with the seats facing each other, and built upon English models

by the Greens of Hoboken. The first woman to ride upon the train

was Madam Murat, a Bordentown girl, wife of Prince Murat and niece

by marriage to Napoleon Bonaparte.

The advent of the "John Bull " led to the establishment

of the Camden and Amboy shops at Hoboken, where in 1832-33 there

were three locomotives built, while in 1832 from these models

Matthias Baldwin, in Philadelphia, constructed the "Ironsides"

for the Philadelphia and Norristown Railroad Company, now a part

of the Philadelphia and Reading system, and thus established the

Baldwin Locomotive Works in Philadelphia.

While the road was being completed from Amboy to Camden, and

the engineers were contending with problems at the "deep

cut" near the mouth of the Raritan, horses were used to convey

freight and passengers. A section from Bordentown to Hightstown

was finished on September 19, 1832, and on December 17 of the

same year the line was completed to South Amboy. Three freight

cars, with a capacity of six or seven thousand pounds each, were

put in service on January 24, 1833, the goods being conveyed from

Bordentown to Camden by wagon road. In the meantime the railroad

company had acquired control of all steamboat lines upon the Delaware

and from New York to the Amboys. As late as the summer of 1833

relays of horses, "driven continuously on the run,"

took passengers from Bordentown to the Raritan, the trip of thirty-four

miles requiring two and a half hours. Early in September, 1833,

the "John Bull" began service, leaving Bordentown at

seven in the morning and returning at four in the afternoon. The

late fall and winter of 1833 found the road opened from Bordentown

to a point south of Rancocas Creek, and in January, 1834, the

road was completed to Camden, and the single track system of sixty-one

miles was opened for continuous travel between New York and Philadelphia.

The inauguration of the Camden and Amboy Railroad and the success

of the plan, its stock selling for $134 in July, 1835, had led

to the presence of rival corporations. Securing a charter from

the State of Pennsylvania upon the 23d of February, 1832, the

Philadelphia and Trenton Railroad Company had constructed a line

in 1833 from Morrisville, opposite Trenton, to Bristol, which

in 1835 had been extended to Kensington, now the great shipbuilding

center of Philadelphia. This corporation had also secured a majority

of the stock of the Trenton Bridge Company and the Trenton and

New Brunswick Turnpike Company. Upon March 7, 1832, the New Jersey

Railroad was chartered to construct a railroad from Jersey City

to New Brunswick through Newark, Elizabeth, Rahway, and Woodbridge,

with a capitalization of seven hundred and fifty thousand dollars.

The line had been completed to Elizabeth in 1834, and had practically

reached New Brunswick late in 1835. To remove all opposition,

particularly as the Trenton and Philadelphia corporation claimed

that it could lay tracks on the wagon road under the terms of

the charter of the Trenton and New Brunswick Turnpike Company,

the joint companies acquired a controlling interest in the stock

of the Philadelphia and Trenton Company, with its allied corporations,

the Delaware Bridge Company, and the Trenton and New Brunswick

Turnpike Company. On September 26 the Camden and Amboy Company

entered into a " traffic agreement " with the New Jersey

Railroad Company that "the price for passage from New York

to Philadelphia shall be four dollars for day passengers and five

dollars for night passengers, the receipts to be divided in pro

rata proportion as to the length of the respective railroads used

in this transportation, the fare from Philadelphia to New York,

by way of Bordentown and Amboy, to remain three dollars for each

regular passenger and two dollars for forward passengers."

The Philadelphia and Trenton Railroad also agreed to build a railroad

from Bordentown to New Brunswick, the line projected to follow

the canal as far as Kingston and thence across country to New

Brunswick. In spite of the disasters attending the panic of 1837,

and the failure of the Bank of the United States to meet guaranteed

sterling bills of exchange on Baring Brothers in London, Commodore

Stockton sailed for England and raised funds on six per cent.

Bonds amounting to nearly eighty-three thousand pounds. This was

probably one of the first negotiations of American railroad securities

in a foreign market. In September, 1837, the new road was completed

from Bordentown to Trenton, and was used by passengers in 1838.

In spite of the failure of a syndicate of capitalists to meet

their agreements relative to a lease of the joint companies, which

lease, in contemplation, was used by Commodore Stockton to attract

European capital, he succeeded in selling bonds, and overcame

all imputations made against himself and the project that he represented.

For a year and a half no work had been done between Trenton and

New Brunswick, but with the arrival of funds in the spring of

1838 such advancement was made with the enterprise that by January

1, 1839, the twenty-four miles of track was completed. The year

1839 was spent in making certain radical changes, such as rebuilding

the bridge over the Delaware, making it safe to sustain the weight

of the locomotives, the alteration of the gauge of the Camden

and Amboy and the Philadelphia and Trenton lines, thus avoiding

a transfer at Trenton, and the introduction of through cars. By

1840, the first through all-rail line from Philadelphia to New

York was completed.

The report of the Camden and Amboy directors made on the 29th

of January, 1840, shows that in construction several devices of

rail-laying were adopted. On twenty-six miles between South Amboy

and Bordentown the track was prepared by embedding stone blocks,

two feet square, a yard apart. Five-inch holes were drilled in

each block. Attached to these blocks dressed locust chairs fourteen

inches long and from one to two inches thick were fastened. On

these chairs the Stevens "T" rail was laid and

fastened with six-inch spikes. This rail was three and one-half

inches high, with two and one-eighth inches on the upper running

surface, and weighed forty-two pounds to the yard. The ends of

the bars rested on wrought-iron plates or cast-iron chairs, connected

with iron tongues.

Seven miles of the system were laid upon cross oak and chestnut

sleepers, embedded in broken stone, upon stone trenches, and consolidated

with heavy hand pounders. To these sleepers the rail was attached.

At South River for a short distance continuous granite sills,

twelve by fourteen inches, eight to ten feet long, were laid.

To these a flat bar of iron two and a quarter inches wide and

seven-eighths inch thick was attached. After four years' trial

this method was abandoned. Cross sleepers of locust were laid

transversely on the sills and the edge rail was placed thereon.

In Camden and Burlington red cedar piles seven feet long were

driven into the ground about a yard apart. Upon these the edge

rail was fastened. At Pensauken Creek a wooden rail was laid.

The foundation was a plank three and a half inches thick and two

feet in width under each rail. Cross sleepers of oak were placed

every four feet, with blocks two feet long intervening. Upon these

blocks and sleepers a wood rail six inches square, of yellow pine,

rested, with a flat bar of iron two and a quarter inches wide

fastened thereon by spikes and screw bolts.

Of the rolling stock of the Camden and Amboy Company, in 1840,

there were seventeen locomotives and sixty-four passenger cars,

two of these cars having the proverbial "rocking chairs,"

which always attracted the attention of European travellers of

the period, one car of the omnibus type and eight cars for forward

deck passengers, while the construction of the road and its equipment

from 1831 to 1840 had involved the expenditure of $3,220,000.

There has been preserved an interesting memento of the running

time of "Engine No. 8" which gives a fair idea of the

length of time occupied in 1835 in the railroad journey between

Camden and South Amboy. For this distance of sixty-two miles the

running time was five hours and twenty minutes, allowing one hour

and five minutes, an average of fifteen miles an hour, for the

detention of the engine. There were then six stations on the route.

With thirty-nine possible "stops," the slowest local

train of the Pennsylvania Railroad to-day covers the distance

in two hours and a half, while the trip could be made in an hour,

at an average of sixty miles an hour.

In the eastern portion of the State the growth of the railroad

idea was extremely rapid.. Within two years nine companies, having

an authorized capital of $7,140,000, were chartered. Besides the

Camden and Amboy and the New Jersey Companies there were several

corporations that, while organized upon a local basis, with none

of the broad aims of the Camden and Amboy system, are of especial

interest, as illustrative of the development of the industrial

activity in the East Jersey towns.

In 1831, late in January, the Paterson and Hudson River Railroad

Company was incorporated with a capital of two hundred and fifty

thousand dollars. In its charter it was provided that the road

must commence or pass within fifty feet of the intersection of

Congress and Mill Streets, Paterson, thence to Weehawken, terminating

at any suitable point upon the Hudson opposite the City of New

York. In the crossing of the Hackensack the railroad was authorized

to pass over the river near or upon the bridge of the New Barbadoes

Company. The State reserved the right to purchase the road after

the expiration of fifty years from its completion, and required

the payment of a graded per centage upon its capital stock in

lieu of all taxation. In 1831 the Paterson Junction Railroad Company

was chartered to construct a railroad from a point on the Morris

Canal for a distance of one and a half miles to intersect the

Paterson and Hudson River Railroad Company at its Paterson terminal.

Another road, which was never built, was chartered March 8, 1832,

to extend from Paterson to Fort Lee.

The year 1831, so prolific in railroad corporations, marked

the beginnings of the Elizabethtown and Somerville Railroad Company,

which was chartered upon the 9th of February. The road was to

pass as near as practicable by Bound Brook, Plainfield, Scotch

Plains, and Westfield, and had an authorized capital of two hundred

thousand dollars, to which the State reserved the right of subscripting

twenty-five thousand. In 1833 the stock was increased to five

hundred thousand dollars, and legislative authority was given

to extend the road from Somerville by way of Clinton to Belvidere,

and to construct a branch, if necessary, its western terminal

being a point between the mouth of the Musconetcong and Phillipsburg.

The project to thus construct a road from Easton to tidewater

was but one of the manifestations of the development of the great

anthracite coal industry, which had appeared as one of the forces

in the revolutionizing of the industrial life of the United States.

In Pennsylvania the North-western Railroad had been proposed,

extending from the Delaware opposite Belvidere, by the Water Gap

and Stroudsburg, to Pittstown upon the Susquehanna.

New Jersey

RR | Antebellum RR | Contents

Page

This page originally appeared on Thomas Ehrenreich's Railroad Extra Website