The Hudson River

and the

Hudson River Railroad—1851

Published by Bradbury and Guild

HUDSON RIVER, in many points of

view, may be considered one of the most important streams in the

world. It cannot vie with the Mississippi, or the Ohio, and other

rivers, either in size or extent; but, in all other respects,

it is altogether their superior. For steamboat and sloop navigation,

stretching as it does for one hundred and sixty miles inland,

through a rugged chain of Highlands, and carrying tide water the

entire distance, it is certainly unsurpassed.

HUDSON RIVER, in many points of

view, may be considered one of the most important streams in the

world. It cannot vie with the Mississippi, or the Ohio, and other

rivers, either in size or extent; but, in all other respects,

it is altogether their superior. For steamboat and sloop navigation,

stretching as it does for one hundred and sixty miles inland,

through a rugged chain of Highlands, and carrying tide water the

entire distance, it is certainly unsurpassed.

The Hudson rises in a marshy tract in Essex county, east of

Long Lake. Its head waters are nearly four thousand feet above

the level of the sea. After receiving the waters of the Scroon

on the north, and the Sacondaga, which flows from Hamilton county,

on the west, it turns eastward until it reaches the meridian of

Lake Champlain, where it suddenly sweeps round to the southward,

and continues in a direct course to New York. One mile above Troy

it receives the Mohawk River on the west, the latter being the

largest stream of the two at their junction.

The entire length of the Hudson is three hundred and twenty-five

miles. The picturesque beauty of its banks,—forming gentle

grassy slopes, or covered with forests to the water's edge, or

crowned by neat and thriving towns, now overshadowing the water

with tall cliffs, and now rising in mural precipices,—and

the legendary and historical interests associated with numerous

spots, combine to render the Hudson the classic stream of the

United States.

Ships can ascend the river as far as Hudson, one hundred arid

fifteen miles, and steamboats and sloops to Albany and Troy. During

the summer months, the water is covered with vessels of all sorts

and sizes, ascending or descending the stream, from the canal

boat,—of which great numbers, from the line of the Erie canal,

and entering the river at Albany, are daily towed to and from

New York,—to the magnificent steamers, for which this river

for years has been famous.

The width of the river, for twenty-five

miles above New York, is about one mile. Its west bank, for nearly

this whole distance, is bounded by abrupt precipices of trap rock,

termed the PALISADES. Beyond these there is an expansion of the

river to the width of three miles, termed Tappan and Haverstraw

bays, with mountains upon the western shore seven hundred feet

in height. Passing these at Verplanck's Point, forty miles above

New York, the Highlands commence. Here the river is contracted

into narrow limits, and the water becomes of greater depth. This

mountainous region, about sixteen miles in length, may be considered

the most remarkable feature in the Hudson River scenery. The course

of the stream is exceedingly tortuous, and the hills upon both

sides rocky and abrupt. Above these Highlands the country subsides

into but a fertile hilly region, which continues for one hundred

miles.

The width of the river, for twenty-five

miles above New York, is about one mile. Its west bank, for nearly

this whole distance, is bounded by abrupt precipices of trap rock,

termed the PALISADES. Beyond these there is an expansion of the

river to the width of three miles, termed Tappan and Haverstraw

bays, with mountains upon the western shore seven hundred feet

in height. Passing these at Verplanck's Point, forty miles above

New York, the Highlands commence. Here the river is contracted

into narrow limits, and the water becomes of greater depth. This

mountainous region, about sixteen miles in length, may be considered

the most remarkable feature in the Hudson River scenery. The course

of the stream is exceedingly tortuous, and the hills upon both

sides rocky and abrupt. Above these Highlands the country subsides

into but a fertile hilly region, which continues for one hundred

miles.

Hudson River is named after Henry Hudson, by whom it was discovered

in 1609. He entered the southern waters of New York on the 3d

of September. Tradition says that he landed upon Long Island and

traded with the natives. He spent a week south of the Narrows

before he entered the bay. On the 14th, he proceeded up the river.

As he went along, he all the way found the natives on the west

shore more affable and friendly than those on the east, and discovered

that those on one side were at war with those on the other. In

his journal he gives the following account of his reception upon

landing at Hudson, the place which now bears his name:

"I went on shore in one of the canoes with an old Indian,

who was a chief of forty men and seventeen women, and whom I found

in a house made of the bark of trees, which was exceedingly smooth

and well finished within and all round about. I found there a

great quantity of Indian corn and beans; indeed; there lay to

dry, near the house, of these articles, as much as would load

three ships, besides what was growing in the field. When we came

to the house, two mats were spread to sit on; and immediately

eatables were brought to us on red wooden bowls, well made; and

two men were sent off with their bows and arrows to kill wild

fowl, who soon returned with two pigeons. They also killed immediately

a fat dog, and in a very little time skinned it with shells,

which they got out of the water. They expected I would have remained

with them through the night; but this I did not care to do, and

therefore went on board the ship again. It is the finest land

for tilling my feet ever trod upon, and bears all sorts of trees

fit for building vessels. The natives here were extremely kind

and good-tempered; for when they saw that I was making ready to

return to the ship, and would not stay with them, judging it proceeded

from my fear of their bows and arrows, they took and broke them

to pieces, and then threw them into the fire. I found grapes growing

here also, and plums, pumpkins, and other fruit."

It must not be forgotten that the Hudson River was the theatre

of the first successful attempt to apply steam power to the propelling

of vessels, by Fulton, in 1808, less than half a century ago!

Let the sceptic stand upon the banks of the river now, and

see the superb and swift palaces of motion shoot past, one after

the other, like gay and chasing meteors; and then read poor Fulton's

account of his first experiment, and never throw discouragement

on the kindling fire of genius.

"When I was building my first steamboat," said he

to Judge Story, "the project was viewed by the public at

New York either with indifference or contempt, as a visionary

scheme. My friends, indeed, were civil, but they were shy. They

listened with patience to my explanations, but with a settled

east of incredulity on their countenances. As I had occasion to

pass daily to and from the building yard while the boat was in

progress, I often loitered, unknown, near the idle groups of strangers

gathered in little circles, and heard various inquiries as to

the object of this new vehicle. The language was uniformly that

of scorn, sneer, or ridicule. The loud laugh rose at my expense;

the dry jest, the wise calculation of losses and expenditure;

the dull but endless repetition of 'The Fulton Folly.' Never

did a single encouraging remark, a bright hope, or a warm wish,

cross my path.

"At length the boat was finished, and the day arrived

when the trial was to be made. To me it was a most trying and

interesting occasion. I invited many friends to go on board and

witness the first successful trip. Many of them did me the honor

to attend, as a matter of personal respect; but it was manifest

they did it with reluctance, feigning to be partners of my mortification,

and not of my triumph. I was well aware that, in my case, there

were many reasons to doubt my success. The machinery was new,

and ill made; and many parts of it were constructed by mechanics

unacquainted with such work; and unexpected difficulties might

reasonably be presumed to present themselves from other causes.

The moment arrived in which the word was to be given for the vessel

to move. My friends stood in groups on the deck. I read in their

looks nothing but disaster, and almost repented of my efforts.

The signal was given, and the boat moved on a short distance,

and then stopped and became immovable. To the silence of the preceding

moment, now succeeded murmurs of discontent and agitation, and

whispers, and shrugs. I elevated myself on a platform, and stated

that I knew not what was the matter; but if they would be quiet,

and indulge me for half an hour, I would either go on, or abandon

the voyage. I went below, and at once discovered that a slight

mal-adjustment was the cause of the stopping. It was obviated,

and the boat went on; we left New York; we passed through the

Highlands; we reached Albany. Yet, even then, imagination superseded

the force of fact. It was doubted if it could be done again,

or if it could be made, in any case, of any great value."

What an affecting picture of the struggles of a great mind,

and what a vivid lesson of encouragement to genius, are contained

in this simple narrative! If Fulton and his then doubting friends

could witness now the triumphs of steam on the Hudson and

the Mississippi, the Ganges, the Indus, the Thames, the Tigris,

the Nile, and across the broad bosoms of the three great oceans,

how different would be the sensations of both from those by which

they were animated on the first experimental voyage !

HUDSON RIVER RAILROAD

THE project of building a railroad along the banks of Hudson

River, from New York to Albany, was, for a long time, deemed visionary,

and unworthy of consideration. It was argued and believed that,

even if a road could be built through the Highlands, at anything

like a reasonable expense, it could never compete with the river

steamboats, noted as they were for elegance, safety, and speed.

But the fallacy of this belief has been plainly shown.

Two important considerations, above all others, have tended

to convince the public that a railroad along the Hudson was necessary,

and ought to be built. One, and by far the greatest, is found

in the fact that during the winter months, averaging from 90 to

100 days of each year, the river is closed by the ice; and it

proved a serious inconvenience, to say the least, for a channel,

through which from one and a half to two millions of passengers

were conveyed in the summer months, to be closed for the remainder

of the year. The other was the simple saving of time upon the

way. The comparative merits of the two modes of conveyance it

does not become us to discuss. Both will have their supporters

and favorites, and both will unquestionably be forever open to

the public during two thirds of each year. In the winter, when

the river is closed, the railroad must do all the business, both

in passengers and freights, and no person can doubt, that, although

it is now immense, the superior facilities of transit opened by

the railroad will tend to increase it beyond all precedent.

THE ENTIRE LENGTH of the Hudson River Railroad, from Chamber

street to Albany, is one hundred and forty-three miles and a quarter.

As a general feature, the road is constructed directly along the

banks of the river, five feet above high tides. A proper degree

of directness is maintained, and the sinuosities of the stream

avoided, by cutting through the projecting points of land, and,

when necessary, throwing the line a short distance into shallow

water; protecting the embankment from the action of the waves

by a secure wall. Nearly one half of the whole length of the road

is thus protected. At Verplanck's Point, forty miles from New

York, the track is nearly two miles from the river, but in no

other place does it vary as much as one mile from the water's

edge.

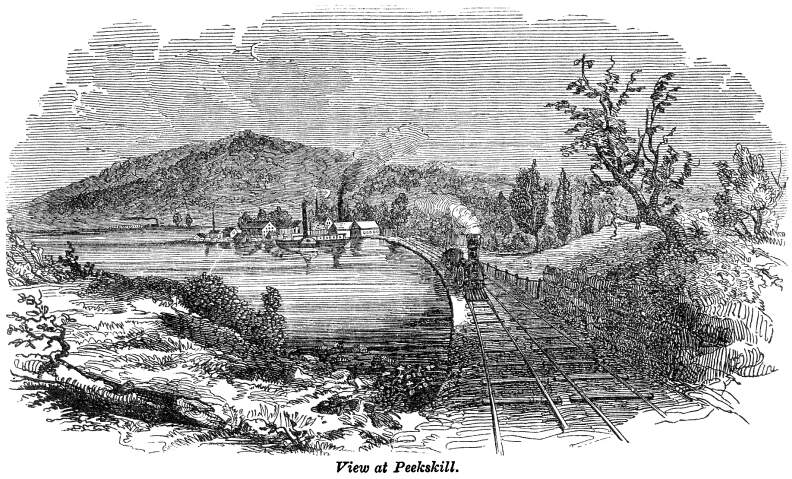

THE GRADES of the road, considering the obstacles surmounted,

are astonishingly regular. Of the whole distance, one hundred

and fourteen miles are upon a dead level, five miles from

one to five feet per mile, thirteen miles of ten feet per mile,

and five miles of thirteen feet per mile inclination, which is

the heaviest grade upon the road. The total rise and fall is two

hundred and thirteen feet only. The shortest curve is at Peekskill

station. This is of one thousand feet radius. Besides this, there

are no curves less than two thousand feet radius, while more than

one half of the whole number are from four to ten thousand feet

radius. The whole number of curves is two hundred and seventy-nine,

there being fifty-eight and a half miles of curved line.

The ROCK EXCAVATION upon the road, as the fact of its following

the banks of the river so closely would lead anyone to suppose,

has been immense. The total amount of rock-cuttings will not vary

much from two millions of cubic yards. On the "Highland"

division alone, (Peekskill to Fishkill, a distance of sixteen

miles,) over four hundred and twenty-five thousand cubic yards

of rock were excavated.

There are EIGHT TUNNELS upon the line, between New York and

Poughkeepsie, as follows:—

|

Name / Place |

Feet in Length |

|

1. At Oscawana, or Peg's Island |

225 |

|

2. Abbott's Point, (Bridge Tunnel) |

100 |

|

3. Flat Rock |

70 |

|

4. St. Anthony's Nose |

400 |

|

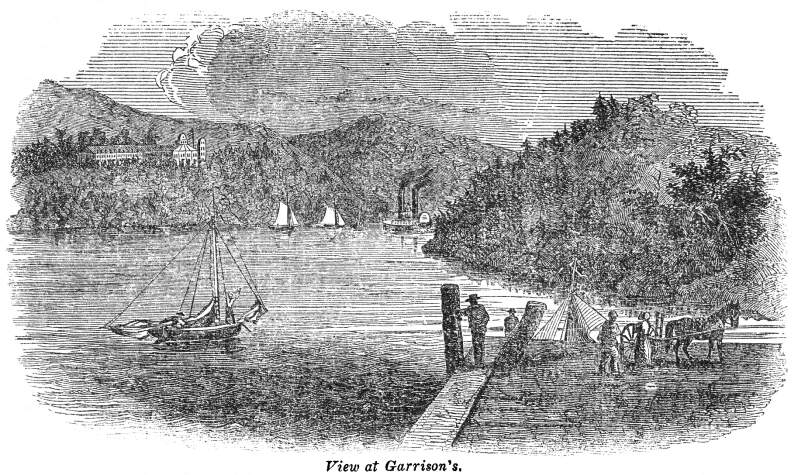

5. Garrison's, at Phillips' Hill |

900 |

|

6. Breakneck Hill |

400 |

|

7. New Hamburg |

1400 |

|

8. Milton Ferry |

100 |

|

TOTAL |

3595 |

All the above tunnels are through solid rock, and are twenty-four

feet wide, and eighteen feet high. The rock is so hard that it

forms the arch of the tunnels in all cases except for a part of

the one at Breakneck Hill. Here the appearance of the rock rendered

it probable, in the mind of the engineer, that it might crumble

on being exposed to the atmosphere, and a brick lining was constructed

for the purpose of preventing the loose stone from falling upon

the track. Besides the above tunnels, of natural rock, there are

two constructed of brick at the Sing Sing prison yard.

The whole cost of the Hudson River Railroad, when entirely

finished, will not vary much from nine millions of dollars. Of

this sum the original stock subscription was for 30,165 shares,

amounting to 3,016,500 dollars. The balance is obtained from other

sources. The road was opened on the 29th of September, 1849, for

the transportation of passengers between New York and Peekskill,

a distance of forty miles. On the 6th day of December following,

an additional section of twenty-three miles was opened, extending

to New Hamburg; and on the 31st of the same month, the remaining

distance of nine miles to Poughkeepsie was brought into use.

One characteristic of this road deserves especial mention.

We refer to the system of signal flags, introduced to secure

safety from accidents in running the trains. Flag men are stationed

upon every mile of the road, generally at the curves, or

upon a slight acclivity, where a view of the track for some distance

can be had. Upon the approach of a train, if all is clear ahead,

the flagman displays a white signal. If there be any obstruction

in sight, or a diminished speed be required for any cause, a red

flag is displayed. During the intervals between the trains,

these men daily examine the road, to see that all is secure. If

a chair be broken, a rail loose, or a spike drawn, the evil is

at once corrected, and thus the road is kept in perfect repair.

This is a very important improvement. It may be true that more

caution is necessary upon this road, in consequence of the great

number of curves; yet there would be a less number of accidents,

were this system adopted upon other roads, where a high degree

of speed is desirable.

Commencing at the principal city station, at the junction of

Chamber and Hudson streets, the track is laid through Hudson,

Canal, and West streets, to Tenth avenue, which it follows to

the upper city station, at Thirty-fourth street. Over this part

of the route the rails are laid even with the streets, and the

cars are drawn by what is called a "dumb engine." This

is considered a great improvement over the use of horses, for

drawing the cars through the streets, where, by the corporation

regulations, locomotives are not allowed to run. This engine appears

very much like an ordinary freight car. The machinery is entirely

out of sight, and it is made to consume its own smoke. While passing

through the city, it is preceded by a man on horseback, who gives

notice of its approach by blowing a horn. At Thirty-fourth street,

the line curves into Eleventh avenue, the dumb engine is detached,

and the regular locomotive takes the train. As far as Sixtieth

street, the track is laid upon the street grades, which are somewhat

undulating. At this point the regular grades of the road begin.

Passing Manhattanville and Carmansville, the first obstacle

of any importance was the heavy rock-cutting at Fort Washington

Point, nine miles above the city. This excavation is in solid

rock, fifty-six feet deep at the highest point, and one hundred

rods in length. The rock taken from this cut amounted to nearly

fifty thousand cubic yards. It was used to construct the protection

wall near this place. From this point, suspended from high poles,

to the high ground on the opposite side of the river, are the

various telegraph lines which extend south from New York. These

were at first sunk in the stream, but they received so much damage

from the anchors of vessels navigating the river, that it was

found necessary to suspend them, in this manner, out of the reach

of danger.

Twelve miles from the city, the line crosses Spuyten Duyvel

Creek. Here is a draw-bridge to allow vessels which navigate the

river to pass into the creek, and also several hundred feet of

pile bridge to allow the free passage of water in and out of the

bay. Spuyten Duyvel Creek falls into what is called Harlem River,

and separates Manhattan, or New York Island, from the main land.

From this point the line proceeds along close to the river,

passing Yonkers, Hastings', Dobbs' Ferry, Tarrytown, to Sing Sing.

This part of the line is level. At Sing Sing the road passes through

the yard of the State Prison, directly in rear of the main building.

The track is several feet below the yard. Two arches of brick,

of twenty-four feet span and six hundred feet in length, are here

constructed, one upon each side of the yard, for the purpose of

rendering it secure.

A short distance above Sing Sing, the road crosses the bay

formed by the junction of the Croton and Hudson rivers. The distance

across is about one mile. A draw-bridge is here constructed; the

remaining part of the distance being partly well protected embankments,

and partly pile bridge.

The line now crosses Teller's Point, a narrow neck of land

extending more than half way across the river, and dividing Tappan

and Haverstraw Bays, so called; the former being below, and the

latter above, this point. Here there is an extensive excavation

through sand and gravel for nearly half a mile. More than four

hundred thousand cubic yards of earth were removed from this cutting.

Passing this, the track follows again close upon the banks of

the river to Oscawana Island, where the first tunnel through solid

rock is passed. Half a mile above this, the road takes a curve

inland, to avoid Verplanck's Point. Here there is some heavy rock

cutting, and, to accommodate the road to a brick-yard near at

band, another short tunnel was made.

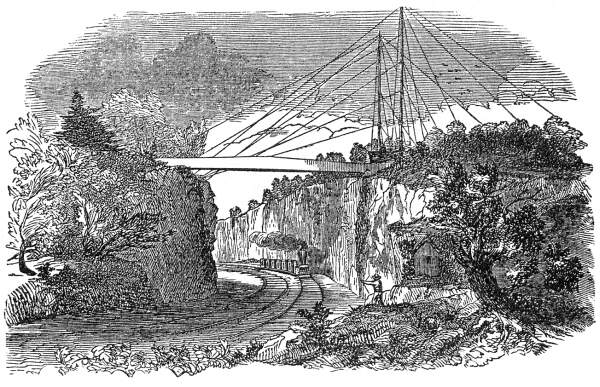

Between this point and Peekskill station the road makes its

greatest divergence from the river; and, at the highest point,

passes over a summit of 34 feet, by a rising and falling inclination

of 13 feet per mile.

At Peekskill, between the 42d and 43d miles, the line curves

to the left more than a quarter of a circle. A little north of

the village it is carried across the bay, at the mouth of Peekskill

Creek, a distance of three quarters of a mile; part of the distance

by a pile bridge eight hundred feet in length, with draw for vessels,

&c., and the remainder by embankment. At this point the Highland

division commences. Two miles north of Peekskill is the third

tunnel upon the line, which is denominated Flat Rock tunnel; and

within another mile the line passes through the projecting point

of Anthony's Nose, by a fourth tunnel, with heavy and extensive

rock cutting at each exit.

For a considerable distance along the Highlands, the mountains

have an elevation of from one thousand to fifteen hundred feet,

and shut down close to the water's edge. In many places the road

is formed by cutting a large portion or even the whole of its

width into the rock, leaving a perpendicular natural wall upon

the east side, from ten to thirty, and even forty, feet high.

In one case, six miles above Peekskill, where the road is formed

across the outlet of a small brook, much trouble was occasioned

by the sinking of the embankment. Several months after this portion

was graded and ready for the rails, and a portion of the track

was laid, while passing over it with a horse and car-load of rails,

the embankment for more than a hundred feet went down so suddenly

that the horse, car, and rails were overwhelmed, and two men on

the car escaped with difficulty. It is now constructed upon piles,

and probably secure. Similar difficulties, though less important,

occurred at five different points between Peekskill and West Point.

The elevated ground opposite West Point, at Phillips' Hill,

is passed by a tunnel nine hundred feet long, being the fifth

upon the road. Emerging from this, to avoid a sudden bend in the

river, the line is carried across a sort of bay, by a pile bridge

nearly a mile in length, and extending more than one third of

the distance across the stream. On reaching the shore it intersects

a short branch built for the accommodation of the iron works at

Cold Spring. The road passes directly through the village of Cold

Spring, where two formidable rock cuts were encountered.

From this point to Breakneck Hill

the road is nearly straight, notwithstanding the numerous bays

in the river, and the rocky projections from the hills, presenting

obstacles which seem to bid defiance to the skill of the engineer.

From this point to Breakneck Hill

the road is nearly straight, notwithstanding the numerous bays

in the river, and the rocky projections from the hills, presenting

obstacles which seem to bid defiance to the skill of the engineer.

At Breakneck, the road passes the sixth tunnel, and follows

along close to the water, crossing Fishkill Creek, in rear of

Dennings' Point. Here the Highlands end. North of the creek is

a cutting in blue clay, more difficult to excavate, in some respects,

than the hard rock cuts.

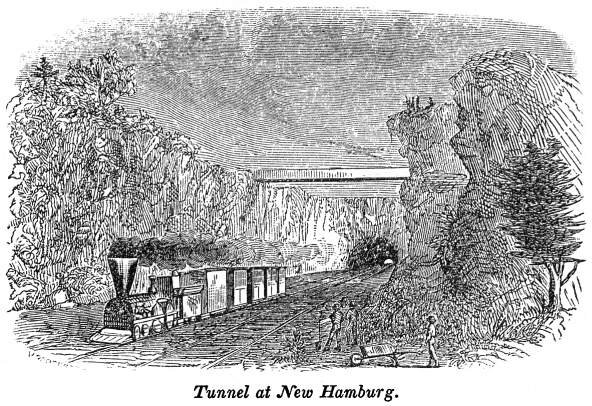

North of Wappinger's Creek, which is crossed by a pile bridge

at the village of New Hamburg, the road encounters a ridge of

limestone rock, very hard and compact. Here it was necessary to

construct a tunnel of considerable length, the seventh upon the

line. To expedite the work, two shafts were sunk, one seventy-two

feet from the surface of the ground, the other to the depth of

fifty-three feet. A large portion of the tunnel excavation was

drawn up through these shafts by steam power; and the water, which

at some periods was troublesome, was disposed of in the same way.

The eighth tunnel was about one mile north of Milton Ferry.

At Poughkeepsie the line passes through the lower part of the

place, all the roads leading to the river being carried over the

railroad. North of this station are two heavy sections. Indeed,

of the twenty-six miles extending from Poughkeepsie to Tivoli,

the north line of Duchess county, seven are rock cuttings. A line

was originally surveyed from Poughkeepsie to Albany, passing through

the country away from the river, in some places being as much

as seven miles distant; but, for various reasons, it was abandoned.

Above Tivoli, with one or two inconsiderable exceptions, the

road follows close to the river the whole remaining distance to

Greenbush. As a general thing, the track is five feet above high

tide-water, and very few excavations or other works are of sufficient

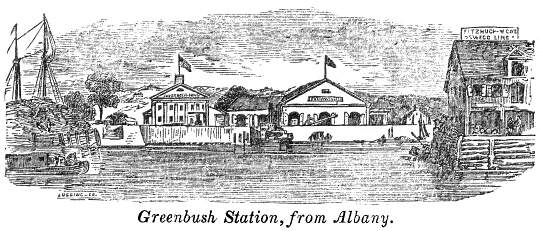

importance to deserve especial notice. At Greenbush the track

is united to that of the "Troy and Greenbush" road,

six miles in length, which has been leased to the Hudson River

Company for a term of years.

The Hudson River Railroad is probably one of the very best

constructed roads in America. The road bed, generally, is thirty

feet wide at the top; the protection wall three feet in thickness,

and carried five feet above ordinary high tides; the rails weigh

seventy pounds per yard, and the outer rail, in all cases of exposure

to the river, is ten feet from the top of the wall, affording

a wide margin for the washing of the bank, and ample security

against running the cars into the water in cases of accident.

The time proposed for running the trains between New York and

Albany is four to four and a half hours. This will be likely to

vary somewhat with the season, though it is believed that it will

never exceed the longest time named. This will be a saving of

at least four hours to each passenger, over what would have been

occupied on board a steamboat,—an important consideration,

certainly. By the terms of the charter, the fare through is not

to exceed three dollars at any season. This will unquestionably

be the fixed price during the winter, and must be considered very

reasonable. Whether the competition of the boats, during open

river navigation, will be such as to induce the company to reduce

the fare in the summer, time will determine. Considering the great

obstacles surmounted in constructing the road, and the saving

of time passing over it, three dollars, at all seasons, cannot

be called an unreasonable fare, while, for the winter months,

none will deny that it is extremely low.

CITIES, TOWNS, AND VILLAGES UPON

HUDSON'S RIVER

NEW YORK is the largest, most wealthy, most flourishing

of American cities; the great commercial emporium of the United

States, and one of the greatest in the world. The compact portion

of the city is built upon the southern end of Manhattan Island,

and now extends to Thirteenth street, which is the first street,

as you proceed northwardly, that runs in a straight line quite

across the island. The distance from the Battery to this point

is nearly three miles. Above this, for at least two miles further,

the space is rapidly being filled up by elegant dwelling-houses.

No city in the world possesses greater advantages for foreign

commerce and inland trade. In addition to the main sea approach

through the Narrows to the harbor, the channel through East River

to Long Island Sound, and the Hudson River, two long lines of

canals have increased its natural advantages, and connected it

with the remote west; and have rendered it the great mart of,

a vast region, now occupied by industrious millions; while its

railroad facilities of communication with every quarter have made

it the great mercantile centre of the nation. Its progress in

population, trade, and wealth, has probably never been equalled.

In 1800, the population was but 60,000; while, by the late census,

it was found to be about half a million.

Manhattan Island is fourteen miles in length, and averages,

perhaps, one and a half miles in breadth. Its greatest breadth

is at Eighty-sixth street, and is two miles and a quarter. Hudson

River bounds it upon the west, East River on the east, while on

the north it is separated from the main land by Harlem River and

Spuyten Duyvel Creek. In its natural state the surface was somewhat

hilly and marshy, but these inequalities have been reduced to

an almost complete level in that portion occupied by the city,

the ground having merely a gentle slope on each side towards the

water. The highest point upon the island is near Fort Washington,

being about 238 feet above the river.

The harbor, or bay of New York, as it is called, is one of

the finest in the world; safe, commodious, and rarely obstructed

by the ice. It is twenty-five miles in circumference, easy of

access, completely sheltered from storms, and of sufficient size

and depth of water to contain the united navies of the world.

The principal entrance between Staten and Long Islands is about

half a mile wide, and well defended by strong fortifications.

There are also batteries on several other islands, further up

the bay. The variegated scenery upon its shores, together with

the neatly built cottages, the country seats of opulent citizens,

and the fine view of the city in approaching from the "Narrows,"

impart to this harbor a beauty probably unsurpassed by that of

any other in the world.

Many of the streets at the southern extremity of the city are

narrow and crooked. The greater part of those built latterly are

laid out with more care. Broadway, the principal street, is eighty

feet wide, entirely straight, and extends from the Battery to

Union Square, a distance of nearly three miles. It is the great

promenade of the city, being much resorted to by the gay and fashionable;

and few streets in, the world exceed it in the splendor and bustle

it exhibits. Here is a continued stream of carriages, wagons,

drays, omnibuses, and all sorts of vehicles designed for business

or pleasure; on the side-walks, crowds of pedestrians saunter

along or hurry by, while the sound of various languages meets

the ear. No person possessing a spark of curiosity should fail

to look upon Broadway from the spire of Trinity church.

PUBLIC SQUARES, &C.—The Battery is situated

at the extreme south end of the city. It contains eleven acres.

It is neatly laid out with gravelled walks, and planted with trees.

From this place is a fine view of the harbor, the islands, and

of the shores of New Jersey and Staten Island. — The Park

is a triangular area of about ten acres, enclosed by Broadway,

Chatham, and Chamber streets, and surrounded by an iron fence.

It contains the City Hall and other buildings. Besides a large

number of fine trees, it is embellished by a fountain supplied

by the Croton aqueduct. — The Bowling Green, situated

near the Battery, is of an oval form, and also contains a neat

fountain supplied as above. — St. John's Park, in

Hudson Square, is beautifully laid out in walks, with shade trees,

and kept in excellent order. — Washington Square, or

Parade Ground, in the north part of the city, contains

about nine and a half acres, surrounded by a wooden fence. A portion

of this square was formerly the Potter's Field. — Union

Square is situated at the termination of Broadway. It is of

an oval form, enclosed by an iron fence, and its centre ornamented

by a fountain. It is the neatest square in New York. There are

other squares further up the city, which are extensive, but not

yet laid out.

PUBLIC BUILDINGS, &C.—The city of New York

can boast of many splendid public buildings. It has about two

hundred and fifty churches, many of which are magnificent and

costly structures. Trinity Church, standing in Broadway,

at the head of Wall street, may be considered the most splendid

edifice of the class in the city. It is built throughout of sandstone,

without galleries, and cost nearly half a million of dollars.

The height of its spire is 283 feet. Visitors have access to the

tower at all times, except when the building is occupied for religious

purposes. A small fee is expected by the person in attendance.

This tower affords the most splendid panoramic view to be seen

on this continent. Ascending the stairway, you reach a landing

on a level with the ceiling of the church, from which there is

a view of the elegant interior. You next reach the belfry, where

the chime bells are hung, which so frequently ring out their solemn

peal. Upon reaching the highest landing, a most superb view meets

your gaze. The city, busy with life and animation, lies at your

feet, spread out like a map; while, far and wide, in every direction,

the country, rivers, villages, and islands, are scattered before

you, arrayed in all the attractions with which nature and art

have invested them.

The City Hall, one of the finest buildings in New York,

has a commanding situation in the centre of the Park, and shows

to great advantage. It is built of white marble, with the exception

of the rear wall, which is of brown freestone. The corner-stone

was laid in 1803, and it was ten years in building. In the structure

are twenty-eight offices, and other public rooms, the principal

of which is the Governor's room, a splendid apartment appropriated

to the use of that functionary on his visiting the city, and occasionally

to that of other distinguished individuals. The walls of this

room are embellished with a fine collection of portraits of men

celebrated in the naval, military, or civil history of the country.

In the Common Council room is the identical chair occupied by

Washington when President of the first American Congress, which

assembled here.

The Exchange, on Wall street, is a noble building,

constructed of Quincy granite, well worth a visit from the stranger.

It is built upon the spot occupied by the old Exchange, which

was consumed by the great fire in December, 1835. No wood, except

for the window-frames and doors, is used in this structure.

The Custom House is also upon Wall street. It

is built of white marble, similar to the model of the Parthenon

at Athens. It is, like the Exchange, fire-proof.

Besides many other objects within the city worthy of notice,

visitors will find much to interest them in the immediate vicinity.

New York is connected with the neighboring cities and villages

by a great number of ferries, on some of which boats run the entire

night. Of these, no less than five connect New York with Brooklyn.

GREENWOOD CEMETERY is in the south part of Brooklyn,

at Gowanus, three miles from the Fulton ferry. Stages run from

nearly every boat during the day to this charming spot, carrying

passengers at a trifling charge.

This cemetery was incorporated in 1838, and contains two hundred

and forty-two acres of ground, about one half of which is covered

with wood of a natural growth. It originally contained but one

hundred and seventy-two acres; but recently seventy more have

been purchased and brought within the enclosure. Free entrance

is allowed to persons on foot during week days, but on the Sabbath

none but proprietors and their families are admitted. The grounds

have a varied surface of hills and valleys. The elevations afford

beautiful and extensive views of New York, Brooklyn, the harbor,

Staten Island, and the distant New Jersey highlands.

Greenwood is traversed by winding avenues and paths, and visitors,

by keeping the main avenue, called Tim TOUR, as indicated by the

guide-boards, will obtain the best view of the grounds and the

most interesting monuments. Unless this caution is observed, they

may not easily find the place of exit. This delightful spot now

attracts much attention, and has become a place of great resort.

The UNITED STATES NAVY YARD, at Brooklyn, will attract

the notice of visitors to that city. It is situated upon the south

side of Wallabout Bay, in the north-east part of the city. It

occupies about forty acres of ground, enclosed by a high wall.

There are here two large ship-houses for vessels of the largest

class, with workshops, and every requisite necessary for an extensive

naval depot. A dry dock constructed here cost about one million

of dollars.

At the Wallabout were stationed the prison-ships of the English

during the Revolutionary war, in which so many American prisoners

perished from bad air, close confinement, and ill-treatment.

ROCKAWAY BEACH, a celebrated and fashionable watering

place, on the Atlantic sea-coast, is about twenty miles south-east

of New York. The Marine Pavilion, a splendid hotel erected here

upon the beach, a short distance from the ocean, is furnished

in a style befitting its object as a place of summer resort. The

best route to Rockaway is by railroad to Jamaica, thence by stage.

FORT HAMILTON, one of the fortifications for protecting

the entrance to the bay of New York, is situated at the "Narrows,"

seven miles from the city. There is an extensive hotel here for

the accommodation of visitors. The Coney Island steamboat stops

to land and receive passengers here.

CONEY ISLAND is situated at the extreme south-west point

of Long Island, four miles below Fort Hamilton. A narrow inlet

separates it from the town of Gravesend, to which it belongs.

It has a fine beach, fronting the ocean, and is much visited during

the hot summer months for sea-bathing. A steamboat plies regularly

between the city and Coney Island during the summer.

Two railroads only extend directly into New York,—the

Hudson River, and the Harlem, both of which have their passenger

stations in Chamber street. The Harlem road extends across Manhattan

island, crossing the river at Harlem, and thence follows the Bronx

River to Williams' Bridge, and in that direction to White Plains,

Croton Falls, and Dover. When completed, it will unite with the

Western (Massachusetts) road at Chatham Corners. At Williams'

Bridge the New Haven road begins, extending through New Haven,

Hartford, Springfield, and Boston, eastwardly.

YORKVILLE, upon the Harlem road, five miles from City

Hall, is a small village, one of the suburbs of New York. The

receiving reservoir is about one quarter of a mile from this place.

A tunnel through Prospect Hill, a distance of five hundred feet,

was necessary to enable the cars to run to Harlem.

HARLEM, eight miles from City Hall, is quite a manufacturing

place. It was founded by the Dutch in 1658, with a view to the

amusement and recreation of the citizens. What was then a rural

and retired spot, will soon be but a part of the city.

JERSEY CITY, west side of Hudson River, and opposite

New York, is connected with it by a ferry over a mile in length,

the boats on which are constantly plying. Population, 6856. It

is important principally as a diverging point between the north

and the south. The Philadelphia Railroad station, the dock for

the Cunard steamers, and the Paterson Railroad station, are in

Jersey City. The passengers over the Erie Railroad take the cars

of the Paterson road at Sufferns' Junction, thirty-four miles

from New York. This route is 13 miles shorter than that by way

of Piermont and the Hudson River.

The Morris Canal, uniting the Delaware River at Philipsburg

with the Hudson, terminates here. This canal is one hundred and

one miles in length, and cost $2,650,000.

HOBOKEN, directly above Jersey City, on the west side

of the river, is a popular place of resort by the citizens of

New York. The walks, which are shaded by large trees, extend for

two miles along the banks of the Hudson, terminating with the

Elysian Fields. From the heights, a short distance from the stream,

there is a beautiful and picturesque view of New York, the bay,

and the hills of Long Island, in the distance. Scattered over

these gentle acclivities are many fine villas and country-seats

of opulent citizens, which give the place an air of rural comfort

not often met with in such close proximity to a large city. A

little above this, on the same side, is WEEHAWKEN. It is close

by the water's edge, and screened in from the land view by a precipitous

ledge of rocks, which gives it the privacy usually sought for

in such places. Here it was that the well-known General Hamilton

fell in a duel with the notorious Colonel Burr. Their quarrel

was strictly a political one, arising from some expressions used

by the former, which resulted in a challenge. The parties met

on the 11th of July, 1804. At the first shot, Hamilton fell, mortally

wounded. He was taken to New York, where he died the following

day, aged forty-seven years. There was formerly a monument standing

upon the spot where he fell, but it is now removed.

MANHATTANVILLE, 7½ miles from New York, is the

first station upon the Hudson River Railroad. It is, in fact,

but a part of the city. It is a small but thriving village, pleasantly

situated, surrounded by hills. About half a mile distant, upon

the high ground, occupying a commanding situation, stands the

Lunatic Asylum. Attached to it are forty acres of land, neatly

arranged into gardens and pleasure-grounds. The view of Hudson

River and the surrounding country from this place, is very fine.

CARMANSVILLE, or 152D STREET, nine miles, is the next

station. Like the last-mentioned place, it is merely one of the

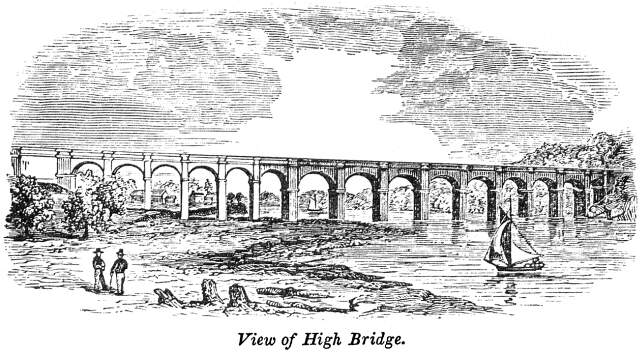

suburbs of New York. The HIGH BRIDGE, so called, carrying the

Croton Aqueduct across Harlem River, is only one mile from this

station; and, it being an easy and retired walk, affords a cheap

and pleasant way to visit that noble structure. Trinity Church

Cemetery is located here, upon the side hill, overlooking the

river.

One mile above Carmansville, upon the top of a projecting point,

stands Fort Washington. It occupies a commanding situation. It

was held by General Washington for some time after New York was

occupied by the British, in 1776; but on the 16th of November,

in that year, it fell into the hands of the enemy, after a violent

assault,—during which the assailing party lost eight hundred

men,—with two thousand Americans, under Col. Magaw, as prisoners

of war.

Opposite Fort Washington, upon the brow of the Palisades, and

three hundred feet above the river, is the site of Fort Lee. Soon

after Fort Washington was captured, this also was given up, the

Americans retiring to the Highlands.

At Fort Lee the Palisade rocks begin, presenting, all along

on the west margin of the river, for many miles, a perpendicular

wall of rock, varying from two to five hundred feet in height.

These are sometimes covered with brushwood, sometimes capped with

stunted trees, and sometimes perfectly bare; but always showing

the upright cliff, which constitutes the most striking feature.

At the foot of this curious wall is a pile of broken rocks and

debris; all or most of which has evidently crumbled away from

the face of the precipice. Much of this is removed every year,

and used for building purposes. In many places there is hardly

room for a foot-path on the shore of the river; while here and

there the space is considerable; and, occasionally, a fisherman's

but is seen, built upon the very margin of the stream.

The name Palisades is given to this curious cliff, probably,

from the ribbed appearance of some portions of it, which seem

like rude basaltic columns, or huge trunks of old trees, placed

close together in an upright form, for a barricade or defence.

The water, a very few feet from the shore, is deep, being what

is termed a "bold shore," and vessels run quite close

to the cliffs. Any one who has visited the celebrated West Rock,

at New Haven, Conn., will at once associate its general appearance

with the Palisades, though the character and extent of their formation

are entirely different

TUBBY HOOK, eleven miles. This station is situated on

a romantic and secluded spot, near the northern extremity of New

York Island. The proximity of this location to the city, and the

facilities afforded by railroad for passing to and from New York,

must, in time, make this a very pleasant and desirable country

residence, though at present there are very few dwellings in the

neighborhood.

SPUYTEN DUYVEL, twelve miles. The Creek of the same

name, which branches from the Hudson at this point, flows into

Harlem River, and forms Manhattan Island. There is a draw here,

but very few vessels ever pass it.

YONKERS, in the town of the same name, sixteen miles

from New York, is situated at the mouth of Sawmill River, which

here falls into the Hudson. This village is a favorite summer

retreat from the city, and is rapidly increasing in population.

The pleasantest locations are upon a narrow plateau, a short distance

from the river. The line of the Croton Aqueduct bends towards

the Hudson at this place, and for seventeen miles follows along

within about half a mile of the river. In one or two places it

is less than one hundred rods distant. Fordham Heights and Tetard's

Hill, noted in the war of the Revolution, are in this town.

HASTINGS', twenty miles, situated upon the line between

Yonkers and Greensburg, is the next station. There are some fine

country seats here, and a thriving village. Two miles above Yonkers,

the Palisade rocks are highest, and about opposite Hastings' they

recede from the river and disappear. One mile and a half beyond

this station is

DOBBS' FERRY, an important point during the Revolution,

when a ferry was established here. It is a place of considerable

resort during the summer. Four miles above Dobbs' Ferry, near

Tarrytown, is "Sunnyside," the beautiful residence of

Washington Irving. The villa is built upon the margin of the river,

with a neat lawn and embellished grounds surrounding it. It can

be seen from the steamboats in passing up or down the river.

Piermont, on the west bank of the Hudson, is

the starting-point of the New York and Erie Railroad, now completed.

A pier nearly one mile in length extends into navigable water,

and a ferry connects it with the Hudson River Railroad, at DEARMAN

station. Three miles and a half west is the village of Tappan,

celebrated as the head-quarters of Washington during the Revolution,

and as the place where Major Andre was executed, October 2, 1780.

[See Peekskill.]

TARRYTOWN, twenty-six miles from New York, is a thriving

place, situated near the northern boundary of Greensburg. The

railroad here cuts off quite a point of land and divides the village,

leaving a considerable part of it on the side next to the river.

The newly built portion is on a slight eminence east of the railroad,

and partly hid from view.

Tarrytown is famed, in the history of the American war, as

the place where Andre was arrested by Paulding and his associates.

The spot, which is well known, is about half a mile north of the

village, on the west side of the road, near a small stream which

falls into the Hudson, near at hand. The remains of Isaac Van

Wart, one of the three captors, are deposited under a monument

to his memory, at a little hamlet of Greensburg, three miles east

of Tarrytown. He died in 1828, aged 69 years.

About two miles or so up the valley of the small stream above

mentioned, sometimes called Mill River, is the place known as

Sleepy Hollow, the scene of Ichabod Crane's encounter with the

"Galloping Hessian," so graphically described by Irving,

in his Legend of Sleepy Hollow. It is a retired spot, partly overgrown

by trees, where the perfect stillness is broken only by the warbling

of the brook which runs through it. Like the story of Rip Van

Winkle, which has clothed the rugged sides of the Kaatskill Mountains

with such mysterious interest, this legend will find a place at

the neighboring firesides for all time to come.

Nearly opposite Tarrytown, on the west side of the river, is

the village of Nyack, once celebrated for its quarries

of red sandstone. The village is prettily built at the foot of

a high cliff, and makes a picturesque appearance from the eastern

shore.

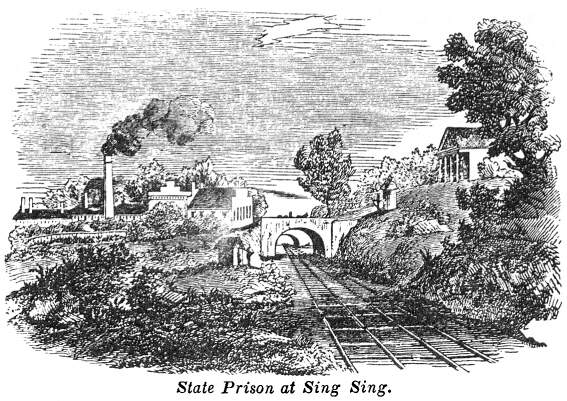

SING SING, thirty-two miles from New York, is situated

partly upon elevated ground, and commands a beautiful view of

the river and the surrounding country. At this place are several

extensive marble quarries. A mineral spring, some three miles

east of the village, has some reputation for its medicinal qualities,

and a large boarding-house was erected there some years since.

Mount Pleasant Academy, for boys, is at Sing Sing. The building

is of Sing Sing marble, and stands upon one of the most retired

streets of the village, commanding an extensive prospect of the

river and adjacent country. There is also a boarding-school for

young ladies at Sing Sing, elegantly located.

The principal object of interest

here is the State Prison. It is situated upon the bank of the

Hudson River, ten feet above high water mark. The railroad runs

directly through the prison yard. The prison grounds comprise

one hundred and thirty acres, and may be approached by vessels

drawing twelve feet of water. The keeper's house, workshop, &c.,

are built of rough "Sing Sing marble," quarried from

lands owned by the state in the vicinity. The main building is

four hundred and eighty-four feet in length, running parallel

with the river, and forty-four feet in width. It is five stories

high, with two hundred cells upon each floor; in all, one thousand

cells.

The principal object of interest

here is the State Prison. It is situated upon the bank of the

Hudson River, ten feet above high water mark. The railroad runs

directly through the prison yard. The prison grounds comprise

one hundred and thirty acres, and may be approached by vessels

drawing twelve feet of water. The keeper's house, workshop, &c.,

are built of rough "Sing Sing marble," quarried from

lands owned by the state in the vicinity. The main building is

four hundred and eighty-four feet in length, running parallel

with the river, and forty-four feet in width. It is five stories

high, with two hundred cells upon each floor; in all, one thousand

cells.

The system and discipline of this prison owe their origin to

Elam Lynds, for many years agent of the Auburn prison. The convicts

are shut up in separate cells at night, and on Sundays, except

when attending religious services in the chapel. While at work,

they are not allowed to exchange a word with each other, under

any pretence whatever; nor to communicate any intelligence to

each other in writing; nor to exchange looks, or winks, or to

make use of any signs, except such as are necessary to convey

their wants to the waiters. The plan of confining each convict

in a separate cell during the night, or the "Auburn system,"

as it is called, was adopted at the Auburn prison in 1824. The

prison at that time contained but five hundred and fifty cells.

Being, therefore, totally insufficient to accommodate all the

convicts of the state, an act was passed by the Legislature, authorizing

the erection of a new one. Sing Sing was selected as the location,

and Captain Lynds as agent to build it. He was directed to take

from the Auburn prison one hundred convicts; to remove them to

the ground selected for the site of the new prison; to purchase

materials, employ keepers and guards, and to commence the construction

of the building. The reasons for taking the convicts from Auburn,

and transporting them so great a distance, instead of from New

York, were, that the convicts at the former place had been more

accustomed to cutting and laying stone, and had been brought by

Capt. Lynds into the perfect and regular state of discipline he

had established there, and which was indispensably necessary to

their safe-keeping in the open country, and the successful prosecution

of the work.

The party arrived at Sing Sing, without accident or disturbance,

in May, 1825, without a place to receive them, or a wall to enclose

them. A temporary barrack was erected to receive the convicts

at night, and they were then set at work building the prison,

each one working at his trade,—one a carpenter, another a

mason, &c.,—all the time having no other means to keep

them in obedience but the rigid enforcement of the strict discipline

adopted at the Auburn prison. For four years the convicts, whose

numbers were gradually increased, were engaged in building their

own prison, and finally completed it in 1829. The prisoners, since

the building was completed, have been engaged considerably in

quarrying marble from the extensive ledges in this town.

Opposite Sing Sing, across Tappan Bay, which is widest at this

point, is Verdritege's Hook, a bold headland, rising majestically

from the river. On this mountain there is a crystal lake, about

two miles in circumference, which forms the source of Hackensack

River, and which, though not half a mile from the Hudson, is elevated

three hundred feet above it. This is called Rockland Lake, from

whence large quantities of the very clearest ice are annually

sent to New York. The ice, cut into large square blocks, is slid

down to the level of the river, and, upon the opening of the spring,

it is transported in boats to the city. The Hackensack River falls

into Newark Bay, near Jersey City.

Two miles above Sing Sing, the road crosses the mouth of Croton

River, and Teller's Point, a narrow neck of land extending into

the river about a mile, and dividing Tappan and Haverstraw Bays.

This neck of land, which is almost entirely light and sandy, has

probably been formed by the earth and stones washed down by the

Croton River during the spring freshets, when a large volume of

water is poured into the Hudson at its mouth. The entire length

of the river is about forty miles.

CROTON, thirty-five miles from New York, is a short

distance above Teller's Point, in the southern part of Peekskill

township. It is a small but thriving village, and the nearest

station to the fountain reservoir, the head of the far-famed CROTON

WATERWORKS, by which the city of New York is supplied with pure

water. It is a place well worth visiting. Although not strictly

within our plan, a brief sketch of this great project may not

be uninteresting to the reader.

The building of the Croton Aqueduct

was commenced in 1835. At the charter election of that year, the

citizens of New York were required to vote for or against the

project. There were 17,330 votes thrown; 11,367 of which were

in favor of, and 5,963 against the act of incorporation. On the

4th of July, 1842, the water was let into the reservoir, and on

the 14th of October following, it was brought into the city in

the distributing pipes. The whole cost, including the high bridge

across Harlem River, was about fourteen millions of dollars.

The building of the Croton Aqueduct

was commenced in 1835. At the charter election of that year, the

citizens of New York were required to vote for or against the

project. There were 17,330 votes thrown; 11,367 of which were

in favor of, and 5,963 against the act of incorporation. On the

4th of July, 1842, the water was let into the reservoir, and on

the 14th of October following, it was brought into the city in

the distributing pipes. The whole cost, including the high bridge

across Harlem River, was about fourteen millions of dollars.

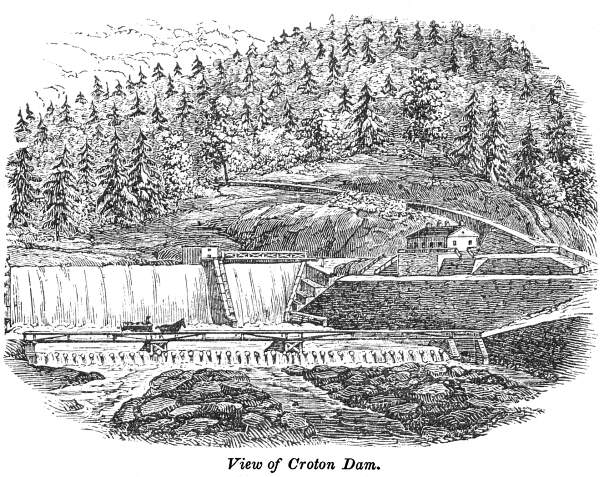

The fountain reservoir is forty miles from New York. The dam

built at this place is about six miles from the junction of the

Croton River with the Hudson, and is 250 feet long, 40 feet high,

70 feet wide at the bottom and 7 feet at the top. It is built

of stone and cement, in a vertical form on the upstream side,

with occasional offsets, and the lower face has a curved form,

so as to pass the water over without giving it a direct fall upon

the apron at the foot; this apron is formed of timber, stone and

concrete, and extends some distance from the toe of the masonry,

giving security at the point where the water has the greatest

action. A secondary dam has been built at the distance of three

hundred feet from the masonry, in order to form a basin of water

setting back over the apron at the toe of the main dam, so as

to break the force of the water falling upon it. This secondary

dam is formed of round timber, brushwood and gravel; it may be

seen in the picture directly under the bridge which extends across

below the main structure.

Pine's Bridge, the place where Major Andre crossed the Croton

River, on his return from his interview with Arnold, occupied

a position which is now about the middle of this reservoir, and

there is at that place a bridge over the reservoir, resting upon

piers and abutments.

The hills which bound the Croton valley, where the reservoir

is formed, are so bold as to confine it within narrow limits;

for about two miles above the dam the average width is about one

eighth of a mile. At this distance from the dam the valley opens,

so that, for the length of two miles more, the width is about

a quarter of a mile; here the valley contracts again, and diminishes

the width until the flow line reaches the natural width of the

river at the head of the lake. The country immediately contiguous

to the shore has been cleared up, and all that would be liable

to impart any impurity to the water has been removed. This gives

a pleasing aspect to the lake, showing where the hand of art has

swept along the shores, leaving a clean margin.

The surface of the fountain reservoir is 166 feet above the

level of mean tide at the city of New York; and the difference

of level between that and the surface of the receiving reservoir

on the island of New York, (a distance of thirty-eight miles,)

is 47 feet, leaving the surface of this reservoir 119 feet above

the level of the mean tide. From the receiving reservoir the water

is conducted a distance of two miles in iron pipes to the distributing

reservoir, where the surface of the water is 115 feet above the

level of mean tide. This last is the height to which the water

may generally be made available in the city.

From this dam the aqueduct proceeds,

sometimes by tunnelling through solid rocks, crossing valleys

by embankments, and brooks and rivers by bridges and culverts,

until it reaches Harlem River. It is built of stone, brick, and

cement, arched over and under. It is 8 feet 5 inches high, and

the water has a descent of 13¼ inches per mile, discharging,

when running two thirds full, 60,000,000 gallons per day. The

aqueduct is carried over Harlem river upon a magnificent bridge

of hewn granite, termed the "High Bridge," 1450 feet

long, with 14 piers and 15 arches; eight of them 80 feet span,

and seven of 50 feet span, 114 feet above tide-water to the top,

and which cost nearly a million of dollars.

From this dam the aqueduct proceeds,

sometimes by tunnelling through solid rocks, crossing valleys

by embankments, and brooks and rivers by bridges and culverts,

until it reaches Harlem River. It is built of stone, brick, and

cement, arched over and under. It is 8 feet 5 inches high, and

the water has a descent of 13¼ inches per mile, discharging,

when running two thirds full, 60,000,000 gallons per day. The

aqueduct is carried over Harlem river upon a magnificent bridge

of hewn granite, termed the "High Bridge," 1450 feet

long, with 14 piers and 15 arches; eight of them 80 feet span,

and seven of 50 feet span, 114 feet above tide-water to the top,

and which cost nearly a million of dollars.

Previous to the completion of this bridge, the water was carried

under the river in two lines of iron pipe of 36 inches in diameter.

In the progress of preparing the foundations for the piers of

the bridge, an embankment was formed across the river, and the

pipe, leaving the aqueduct on the north side of the valley, followed

down the slope of the hill, and, crossing over the river upon

this embankment, ascended on the south side again to the aqueduct.

At the bottom or lowest point in this pipe a branch pipe of one

foot diameter was connected, extending a distance of 80 feet from

it at right angles and horizontally; the end of this pipe was

turned upwards to form a jet, and iron plates fastened upon it,

so as to give any form that might be desired to the water issuing.

The level of this branch pipe is about 120 feet below the bottom

of the aqueduct on the north side of the valley, affording an

opportunity for a beautiful jet d'eau,— such a

one as cannot be obtained at the fountains in the city. From an

orifice of 7 inches in diameter, the column of water rises to

a height of 115 feet, when there is but two feet of water in the

aqueduct.

Visitors to the "High Bridge" can pass and repass

upon the top with the most perfect security. It is a splendid

structure, richly worth the notice of the traveller. Persons wishing

to visit it from the city of New York can take the cars of the

Hudson River Railroad to CARMANSVILLE, which is short of one mile

distant from the Bridge.

After crossing Harlem River, the aqueduct continues to the

receiving reservoir at 86th street, covering 35 acres, and containing

150 millions of gallons. From this point the line proceeds to

the distributing reservoir at 40th street, and from thence the

water is distributed over the city by means of iron pipes.

Haverstraw, on the west side of the river, thirty-six

miles from New York, is a neat village, pleasantly situated upon

a plateau overlooking the river. It has constant communication

with the city by steamboats. Three miles above Haverstraw is Stony

Point, the site of a fort during the Revolution. Directly opposite,

on the east side of the river, is Verplanck's Point. The river

between these two points is only half a mile across, and here

was established what was called King's Ferry, the great highway

between the eastern and the middle states. The ferry was commanded

by the points of land on the two shores. Both these forts were

captured by the British in May, 1779, and their occupation by

the enemy was a great annoyance to the surrounding country; besides

which, a tedious circuit through the Highlands became necessary,

in order to keep up the communication between the two divisions

of the army. Stony Point was re-taken by a body of Americans,

under Gen. Wayne, on the 15th of July following, and the works

destroyed, though Washington did not retain possession of it.

Both forts were, however, evacuated by the British in October

of the same year. A light-house now stands upon the extremity

of Stony Point, a considerable height above the river.

PEEKSKILL, forty-two miles from New York, is one of

the most romantic places upon Hudson River. The village stands

close to the water, near the mouth of Annsville Creek, which falls

into the Hudson a short distance above. The river here takes a

sharp turn to the westward. On the opposite shore is Caldwell's

Landing, which stands at the base of the venerable Dunderburg,

or Thunder Mountain. From the top of this mountain a most lovely

view of the river below is obtained; and, in clear weather, the

city and bay of New York may be seen.

Peekskill is the birth-place of John Paulding, the master

spirit and leader of the trio who arrested Andre at Tarrytown.

Paulding died in 1818, in the 60th year of his age. A monument

has been erected over his remains, which are deposited about two

miles north of the village. It is of marble, a pyramid about fifteen

feet high, enclosed `by an iron railing.

Two miles east of the village stands the dwelling occupied

by Washington while the American army were encamped here. This,

too, was the place where Palmer was executed, by order of General

Putnam, whose memorable reply to Gov. Tryon, who wrote a letter,

threatening vengeance if he were executed, deserves an enduring

record. It briefly and emphatically unfolds the true character

of that distinguished hero. The note ran thus:—

"Sir,—Nathan Palmer, a lieutenant in your service,

was taken in my camp as a spy; he was tried as a spy; he was condemned

as a spy; and, you may rest assured, sir, he shall be hanged as

a spy.

"I have the honor to be, &c.,

"ISRAEL PUTNAM.

"P. S.—Afternoon. He is hanged."

It was in this township, some miles south of the village of

Peekskill, where the train of circumstances commenced, by which

Major Andre was placed in the hands of the Americans, in 1780.

The story is one which will never grow old. It will be remembered

as a reminiscence of the Revolution as long as the memory of Washington

is cherished.

At the time of which we write, West Point was, without question,

the most important post in the United States. Its almost impregnable

strength had been increased by great expense and labor; and it

was an object upon which General Washington perpetually kept his

eye. And perhaps it is not too much to say that the possession

of that fort, by the Americans, was the turning-point of success.

It seems that Arnold, who was a spendthrift, notwithstanding

his previous brilliant reputation as an officer, had been appointed

commander in Philadelphia, after the British evacuated that city.

Here he adopted a style of living altogether beyond his means;

and he soon found himself loaded with debt. To retrieve himself

he had recourse to fraud and peculation. His conduct soon rendered

him odious to the citizens, and gave offence to government. At

length complaints were made against him; he was tried by a court

martial and sentenced to be reprimanded by the commander-in-chief.

This sentence General Washington, as gently as the circumstances

of the case would admit, carried into execution. Mortified and

soured, and complaining of public ingratitude, Arnold attempted

to effect a loan from the French minister, but without success.

Several months before this, under the assumed name of "Gustavus,"

he had opened a correspondence with Sir Henry Clinton, then at

the head of the British army at New York. There is every reason

to believe that his extreme want of money, and those various public

rebukes, hurried him to the fatal determination to sell his country

for gain. This was early in the year, and it only remained for

him to settle in his mind the manner in which this could so be

done as to produce the greatest advantage to himself. He thought

of West Point, and, his resolution being taken, all his views

and efforts thenceforward were directed to that single object.

Cautiously, so as not to awaken the slightest suspicion, he

hinted to Washington his willingness to assume the command

at West Point. He further prevailed upon Robert R. Livingston,

then a member of Congress from New York, to write to the general,

and suggest the expediency of appointing him to that station.

Various other insidious means were taken by Arnold to gain his

object, and he was at length successful; as, on the third of August,

we find him in full command, ripe for treason and revenge.

Sir Henry Clinton now saw a prospect before him which claimed

his whole attention. To get possession of West Point and its dependent

posts, with garrison, military stores, cannon, vessels, boats,

and provisions, appeared to him an object of such vast importance,

that in attaining it no reasonable expense ought to be spared.

The maturing of this plot was entrusted to Major Andre, an Adjutant

General in his command; and, to facilitate measures for its execution,

the sloop of war VULTURE conveyed him up the Hudson as far as

Teller's Point, where she dropped anchor. The place, as also that

of Andre's landing, is indicated upon the map. During the night

of September 21st, 1780,—while General Washington was absent

at Hartford,—with a surtout thrown over his regimentals,

Andre was put ashore in a boat and had an interview with Arnold,

upon the banks of the river without the American lines. Daylight

the next morning found their arrangements incompleted, and Andre

was induced to go to the house of one Smith, a pliant tool of

Arnold's, near Stony Point and within the American lines, and

remain concealed during the day. Here they had time to mature

their designs.

During the day a gun was brought to bear upon the Vulture,

which obliged her to change her position; and at night, the boatmen

refused to carry Andre on board the sloop. To return to New York,

therefore, by land, was the only alternative left. To render his

situation more safe, Andre laid aside his uniform, and, in a plain

coat, upon horseback, he began his journey. He was furnished with

a passport in the name of John Anderson, signed by Arnold, "to

go to White Plains, or lower, if he thought proper, he being upon

public business by my direction." He was accompanied by the

aforesaid Smith. They crossed the river at King's Ferry, from

Stony Point to Verplanck's, and passed the American works at those

places without suspicion. It was now quite dark, and they were

induced, from the representation of danger which they received

from a patrolling party which they met, to stop for the night

at the house of Andreas Miller, near Crompond, about eight miles

from Verplanck's Point. At the first dawn of light, Andre, who,

according to Smith's testimony, spent a "restless night,"

roused his companion, and ordered their horses to be prepared

for an early departure. They took the road towards Pine's Bridge,

and pressed forward without interruption. Here they breakfasted

at the house of a good Dutch woman; and here Andre and Smith separated;

the former pursuing his way toward Tarrytown, while the latter

returned to his home.

Andre was now upon the "Neutral Ground," as it was

called. This part of the country was greatly infested with a set

of robbers from the "Lower " or British party, denominated

"Cow Boys." They lived within the British lines, and

stole or bought a supply of cattle for the army. It happened that

the same morning on which Andre crossed Pine's Bridge, seven persons,

who resided near Hudson's River, on the neutral ground, agreed

voluntarily to go out in company, watch the road, and intercept

any suspicious stragglers, or droves of cattle, that might be

seen passing towards New York. Four of this party were stationed

on a hill, where they had a view of the road for some distance.

The other three, named John Paulding, David Williams, and Isaac

Van Wart, were concealed in the bushes about half a mile north

of the village of Tarrytown. [See Tarrytown.] As Andre, who had

met with no interruption from Pine's Bridge, approached this spot,

Paulding stepped out and seized his horse by the bridle. The surprise

of the moment put Andre off his guard, and, instead of showing

his pass, he hastily asked, "Where do you belong?" They

answered, "Down below," meaning New York, a true Yankee

reply. Elated with the belief that he was once more among friends,

after so much danger, Andre instantly replied, "So do I"

He then foolishly declared himself to be a British officer, upon

urgent business, and begged that the men would not delay him.

But his mistake was soon apparent. He was taken into the bushes

and searched. In his boots they found six papers, as Paulding

observed, "of a dangerous tendency." Andre now proceeded

to offer his watch, his horse, and large amounts of money, to

be set free. But he pleaded in vain. The nearest military post

was at North Castle, where Lieut. Colonel Jameson was stationed.

To this place Andre was taken.

Andre still passed for John Anderson, and requested permission

to write to General Arnold to inform him that he was detained.

Col. Jameson thoughtlessly permitted the letter to be sent, and

forwarded to General Washington the papers found upon the prisoner,

with a statement of the manner in which he was taken. The General

was then on his return from Hartford, and the express took a road

different from that on which he was travelling, and passed him.

This occasioned so great a loss of time, that Arnold, having received

Andre's letter, made his escape on board the Vulture before the

order for his arrest arrived at West Point.

As soon as Andre learned that Arnold was safe, he flung off

all disguise, and assumed his true character as a British officer.

General Washington referred his case to a board of fourteen general

officers, of which Generals La Fayette and Steuben were members.

They were to determine in what character he was to be considered,

and what punishment ought to be inflicted. They treated Andre

with great delicacy and tenderness, desiring him to answer no

questions that embarrassed his feelings. But, concerned only for

his honor, he frankly confessed that he did not come on shore

under a flag, and stated so fully all facts respecting himself,

that it became unnecessary to examine a single witness. The board,

after due consideration, gave it as their opinion that Andre was

a spy; and that, agreeably to the laws and usages of nations,

he ought to suffer death. His execution took place the following

day. See Tappan.]

Andre was reconciled to death, but not to the mode of dying.

He wrote to Gen. Washington, soliciting that he might be shot,

rather than to die on a gibbet. But the stern maxims of justice

forbade a compliance with this request.

Great, but unavailing, endeavors were made by Sir Henry Clinton

to save Andre. Even Arnold had the presumption to write a threatening

letter to Washington on the subject. An exchange for Arnold was

suggested in an indirect manner, but Clinton would not listen