PENNSYLVANIA AND THE PENNSYLVANIA

RAILROAD

from When Railroads Were New—by

Charles Frederick Carter—1909

PENNSYLVANIA had a hard struggle to become reconciled to the

railroad. Perhaps it was arrogance born of prosperity, for in

early days Philadelphia was the foremost city of the nation, and

the country population was thriving; perhaps it was something

deserving a less charitable characterization which inspired the

desperate resistance to innovation.

The fact remains that the opposition to the railroad in the

Keystone State was more bitter and prolonged than elsewhere. As

a result Pennsylvania paid a higher price than any other commonwealth

for having the blessing of rail transportation thrust upon her.

The plain truth is that the good people of Pennsylvania were

strenuously opposed to anything that smacked of progress. They

were entirely content with pack trains winding single-file over

the mountains between Philadelphia and Pittsburg in charge of

men who carried a bag of parched corn and venison for food and

slept under trees. When turnpikes were proposed a vigorous protest

was raised on the ground that the packers and horse breeders would

be ruined. General Alexander Ogle, member of Congress, started

a campaign of education which was notable for plain speaking.

General Ogle was wont to tell his constituents that one wagon

would carry as much salt, iron and brandy as a whole caravan of

half-starved mountain ponies and that "of all people in the

world fools have the least sense," a remark which was open

to disagreeable inferences.

At last the advocates of the turnpike had their way and Conestoga

wagons supplanted the pack horse. In 1786 a fortnightly stage

coach made the rounds between Philadelphia and Pittsburg. In 1804

this was increased to a daily service and the wagons began to

grow numerous. Taverns sprang up every few miles along the way.

Thus a strong vested interest soon grew up which was able to bring

a powerful opposition to bear when a few radicals proposed canals

as superior to turnpikes.

The clamor of opposition to progress reached a climax when

the extremists attempted to maintain that railroads would be superior

even to canals. The popular view was succinctly expressed by an

old Pennsylvania Dutchman who was listening to General Simon Cameron,

who was making a speech at Elizabethtown in favor of the proposed

railroad from Philadelphia to Lancaster. The General said he hoped

to see the day when he could take breakfast at Harrisburg, go

to Philadelphia, transact business, and return to Harrisburg in

time for a good night's rest. This was too much for the Dutchman,

who called over his shoulder as he turned away in disgust:

"Simon, I always knew you were half cracked, but I never

suspected you were such an ass as to talk that way."

Another vested interest now joined the alliance against the

railroad-the truck farmers in the outskirts of Philadelphia. They

said if a railroad were built the Lancaster truck farmers could

ship their potatoes and cabbages to Philadelphia and thus set

up a ruinous competition with the local farmers. In justice to

the Philadelphia farmers it must be said that their forebodings

proved to be only too well founded. The road to Lancaster was

built and the Philadelphia truck business was destroyed so utterly

that the farmers had to cut up their truck patches into town lots,

any one of which sold for more money than the whole farm could

earn in a lifetime.

John Thomson, who up to that time had always been one of the

most respected citizens of Delaware County, built a quarter of

a mile of crude wooden railroad in 1809 and called upon his neighbors

to witness that one horse could pull with ease a heavier load

on the wooden rails than two horses could drag along the muddy

road.

But the neighbors told John Thomson in plain terms that he

was a fool; whereupon, in extreme disgust, he chopped Pennsylvania's

first railroad up for firewood and said no more about it. That

is, not until his son John Edgar, then a year old, was big enough

to talk to.

Instead of sending the boy to school and giving him a chance

to get on in the world, John Thomson kept him at home and filled

his young head with fool notions about railroads until he left

at the age of nineteen to accept a position as engineer, to assist

in laying out and constructing the first important railroad ever

operated in the State of Pennsylvania.

He stuck to the job until as chief engineer and president he

had extended that apology for a railroad across the Alleghanies

and then to the Mississippi and the Great Lakes, developed and

expanded it into one of the greatest transportation companies

in existence, and, dying, left behind him immortal fame as one

of the foremost constructive geniuses in the history of the railroad.

While young Thomson was at home preparing for his lifework,

Pennsylvania was learning things, too. Summed up, the lesson was

that no community can prosper without adequate facilities for

trade. The opening of the Erie Canal and the building of the Baltimore

and Ohio Railroad demonstrated in a rather pointed way that transportation

was foremost of those facilities.

Colonel John Stevens, of Hoboken, who wore out his life trying

to induce people to build railroads, had applied for a charter

to build a railroad from Philadelphia to Columbia in 1823. Just

to humor an old man it was granted, but not a dollar could be

raised to build even an experimental mile of road, even though

Horace Binney and Stephen Girard, two of the foremost conservative

business men of Philadelphia, permitted their names to appear

as incorporators. They were willing to lend dignity to the scheme,

but lending money was quite a different matter. Other charters

were granted in the next few years, but nothing came of them until

the Philadelphia, Germantown and Norristown Railroad was authorized

by an act of the legislature approved by Governor Wolf February

17, 1831.

With commendable prudence the legislature took care that the

incorporators should not get rich too quickly by expressly providing

that the dividends should not exceed twelve per cent per annum.

In order to keep the profits down to this liberal figure the fare

was limited to one cent a mile. All this legislative caution proved

to be unnecessary, for it was many years before the road paid

any dividends at all, even after the tariff was raised to two

cents a mile. The road was opened for traffic June 6, 1832, with

"nine splendid cars" according to contemporaneous accounts,

which were greatly admired by some thousands of spectators.

The "splendid cars," as a matter of fact, were old

Concord stages, provided with flanged wheels to enable them to

stay on the rails and footboards along which the conductors walked

to collect fares. Horses furnished the motive power.

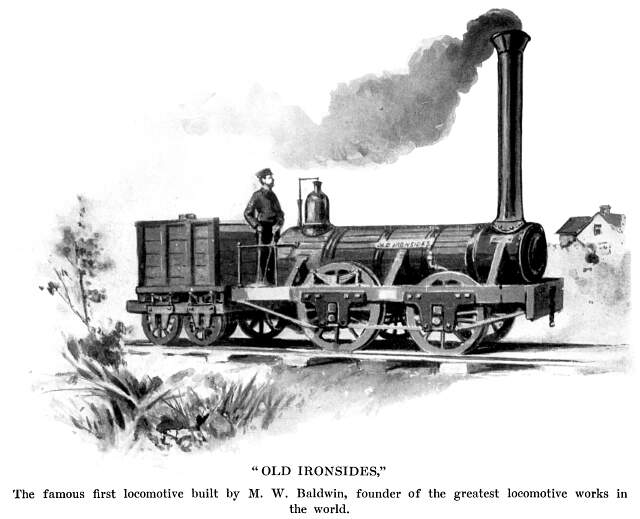

This road is chiefly interesting from the fact that the building

of "Old Ironsides," its first locomotive, laid the foundation

of the great Baldwin Locomotive Works. Matthew Baldwin, the builder,

was a watchmaker by trade. For some unexplained reason a curious

affinity existed between watchmakers and locomotives in early

days. Phineas Davis, who built the prize locomotive for the Baltimore

and Ohio, was a watchmaker. So were Stacy Costell, who organized

the Pennsylvania Locomotive Works in 1831, and Ezekiel Childs,

who also tried his hand at the business. But neither made a success

of it.

Baldwin made himself so famous by building a stationary engine

to run his factory for the manufacture of calico printing rolls,

for the sufficient reason that he had to have an engine and could

not get a satisfactory one in any other way, that his friend Franklin

Peale, the manager of the Philadelphia Museum, asked him to build

a working model of a locomotive, which he wanted as a star attraction

for his museum. Being finished and placed on exhibition on a circular

track April 28, 1831, this model caused a great sensation.

Among those whose interest was aroused were the directors of

the Germantown Railroad, which had then been extended to a point

six miles from Philadelphia.

They asked Baldwin to build a full-sized locomotive for them.

Although he had no patterns, no machine tools, and no experience,

and there were but five mechanics in the city competent to do

any part of the work on a locomotive, Baldwin took the job. The

cylinders were bored out with a chisel fixed in a stick of wood

turned by a crank worked by hand. Six months of hard work were

required to finish "Old Ironsides." On November 23,

1832, the engine was placed in service.

There were no brakes on cars or engine. The only means of stopping

was by reversing the engine, a process as laborious as it was

uncertain. The rock shaft was placed under the footboard. It was

operated by treadles worked by the feet of the engineer which

actuated a loose eccentric for each cylinder. To reverse required

two distinct operations: first to shut off and then throw the

engine out of gear in one direction; next, to throw it into gear

in the other direction—that is, provided it could be done.

But those loose eccentrics were the most nerve-racking devices

that ever tried the patience of a long-suffering engineer. They

responded to the efforts of the treadles when so disposed; when

they took a notion they balked, so the engine could be moved neither

forward nor backward. They caused the poor builder a great deal

of anxiety.

To make matters worse the engine weighed seven tons instead

of the five tons prescribed in the contract. This so displeased

the purchasers that they would have rejected the locomotive but

for the strenuous efforts of Henry R. Campbell, the chief engineer,

a friend of Baldwin, and James Moore, the consulting engineer.

The directors finally accepted Old Ironsides, but would only pay

three thousand five hundred dollars for it instead of the four

thousand dollars they had agreed to pay. This so disgusted Baldwin

that he vowed he would never build another locomotive. But the

Fates had decreed otherwise: he never did anything else but build

locomotives for the rest of his life.

When the opening of the Erie Canal had suddenly diverted Philadelphia's

trade with the West to New York, the State government undertook

what private enterprise would not by creating a Board of Canal

Commissioners to construct improved avenues of communication with

the western part of the State. It was agreed that canals were

the best system of transportation, but, owing to the mountainous

character of the State, railroads might have to be built to fill

in the gaps between canals.

The Board of Canal Commissioners were careful to have it understood,

however, that they favored railroads only as a last resort. In

their annual report published in December, 1831, they stated their

position thus clearly:

"While the Board avow themselves favorable

to railroads where it is impracticable to construct canals, or

under some peculiar circumstances, yet they cannot forbear to

explain their opinion that the advocates of railroads generally

have greatly overrated their commercial value. To counteract the

wild speculations of visionary men and to allay the honest fears

and prejudices of many of our best citizens who have been induced

to believe that railroads are better than canals and consequently,

that for the last six years the efforts of our state to achieve

a mighty improvement have been misdirected, the canal commissioners

deem it to be their duty to state a few facts which will exhibit

the comparative value of the two modes of improvement for the

purpose of carrying heavy articles cheaply to market in a distinct

point of view."

After giving estimates of both methods of transportation, in

which the canal appeared to much greater advantage than the railroad,

the report proceeds:

"The introduction of locomotives and

Winans cars upon railroads where they can be used to advantage

will diminish the difference between canals and railroads in the

expense of transportation. But the Board believe that notwithstanding

all improvements which have been made in railroads and locomotives

it will be found that canals are from two to two and a half times

better than railroads for the purposes required of them by Pennsylvania.

"The Board have been thus explicit with a view to vindicating

the sound policy of the Commonwealth in the construction of canals;

yet they again repeat that their remarks flow from no hostility

to railroads, for next to canals they are the best means that

have been devised to cheapen transportation."

The Philadelphia and Columbia Railroad, eighty-two miles long,

was the eastern link in the chain of State works. It was here

that the boy Thomson began his railroad career as engineer.

Work was begun on a twenty-mile section at each end of the

line in April, 1829. By the end of the succeeding year these sections

were ready for operation with horses as the motive power. April

16, 1834, the locomotive Black Hawk made a trip from end to end

of the road, a single track having been completed by that time.

This was merely an inspection trip, and was not regarded as

the opening of the road. The little party which made that long

journey of eighty-two miles can hardly be said to have enjoyed

it, for the Black Hawk was as capricious as a coquette. When it

felt disposed to go, it went; and when it felt the need of a little

rest it stopped until the passengers got tired, when they would

get out and push the sulky machine along.

They found consolation in the fact that the management had

taken the precaution to send a horse-car with relays of horses

to follow them. Although the Black Hawk did get over the road,

the trip was not regarded as a triumph for steam.

The formal opening of the road was on October 7, 1834, after

the double track had been completed. Governor Wolf and staff left

Harrisburg early Monday morning by an express packet on the canal,

which whirled them down to Columbia at the rate of four miles

an hour. Next morning the journey to Philadelphia was continued

by rail.

Governor Wolf was idolized by the people because of his advanced

stand on the questions of public schools and public improvements,

and he may have divided honors with the new railroads on that

memorable day. At all events, there was a holiday all along the

line.

Men left shop and field and office; women their household duties,

and children their schools to cheer the train, and there were

speeches from the rear platform at every stop, just as if it were

a twentieth century political campaign.

There were two trains into Philadelphia that day, run by rival

companies: the Union Line, operated by Peters & Co., and the

People's Line, operated by Osborne, Davis, Kirke & Schofield.

The private car-line is by no means a modern innovation; it was

originated at the very beginning of railroads in Pennsylvania.

The great bugbear of the people three-quarters of a century

ago was monopoly, just as it is to-day. It was considered to smack

too much of monopoly to have a railroad on which cars and track

were both controlled by the State or by a corporation.

The original idea of a railroad in Pennsylvania was a sort

of improved turnpike, to be kept up by the State, upon which any

one who owned a car and could pay the toll was free to come and

go at his own sweet will.

The results of this method of operation were more amusing to

spectators than they were to the man who wanted to get his car

over the road. They were still more unsatisfactory when the Board

of Canal Commissioners proposed to introduce locomotives which

could be used to haul trains for a fee.

This revolutionary step roused a new storm of opposition. Town

meetings were held at which petitions to the legislature for and

against steam were prepared. Thaddeus Stevens was the leader of

the opposition to steam.

Stevens held that if authority to purchase locomotives and

thus place the motive power of the railroad in the hands of the

State were granted the Board of Canal Commissioners; its patronage

and power would be largely increased and the results would be

detrimental to the interests of the people.

Under pressure from the prominent men of his party, fortified

with a promise that he should have a chance at the patronage and

power, Stevens dropped his opposition and an act was passed authorizing

the Board of Canal Commissioners to purchase locomotives. Under

this authority the superintendent was instructed in April to purchase

twenty locomotives, to be ready for use for the spring trade of

1835.

E. F. Gay, the principal engineer, corresponding to a later

day superintendent of motive power, reported on November 7, 1834,

that two locomotives had been received and had been in daily use

for some weeks. These were the "Lancaster" and the "Columbia,"

both built by M. W. Baldwin.

Each weighed eight tons, and had a four-wheeled truck and a

single pair of drivers, which was believed to be the only arrangement

that would take the sharp curves. They were capable of hauling

forty-eight tons gross, or thirty tons of freight. The running

time for seventy-seven miles was eight hours. Fuel, oil, and wages

of the engineer and attendants cost $14.60 a trip.

The Lancaster's performance was so satisfactory that it was

regarded as the standard by which to gauge other locomotives.

It was in continuous service for sixteen years, when it became

too badly worn out to be worth repairing and was consigned to

the ignominious oblivion of the scrap-heap. The Columbia had met

the same fate two years before.

The Board's experience with English locomotives wasn't so satisfactory.

Five of the English locomotives were purchased under the act of

April, 1834. They couldn't pull their trains, and were forever

breaking down.

Finally, they were sold for scrap-iron, the superintendent

declaring in his disgust that the State would have saved money

by giving the English machines away as soon as they were received.

When the locomotives were put in service the fun began in earnest.

There were several companies, called transporters, engaged in

business on the road, each with its own cars. Some made a specialty

of passengers, others of freight.

But the farmer who had a load of potatoes to take to Philadelphia

was still as free to come and go on the railroad as the winds,

so long as he paid the wheel tolls. There were no turnouts by

which one train or car could pass another.

The first man out at one end of the road was, therefore, the

first to reach the other end. The speed of all users of the road

at any given time was, therefore, regulated by the slowest car.

Any one who has lived in a city where the police have too high

a regard for the tender susceptibilities of truck-drivers to enforce

the ordinances regarding the use of the streets, and who has been

compelled to make a street-car journey at the rate of speed adopted

by the coal wagons and drays which hold the track, can fully appreciate

the joys of travel on the Philadelphia and Columbia Railroad in

the early days.

It was the particular delight of a farmer with a pair of crowbaits

attached to a dilapidated four-wheeled car, on which a hatful

of potatoes bobbed about, to stop every few miles to water his

horses with extreme deliberation, get a drink himself, light his

pipe, inquire of a neighbor returning on the other track the price

of potatoes in Philadelphia, look his car over and whittle a wooden

pin to stick in somewhere to keep the crazy thing from falling

to pieces, while a trainload of passengers, drawn by a locomotive

following him, fretted and fumed and swore, and then grew apoplectic

with impotent rage.

Still, railroad travel even under such conditions had its compensations.

There were no stations in those early days. The roadside inns

sprinkled all over the country at intervals of a few miles, in

response to the requirements of stage-coach travel, took their

place. Coaching customs were still kept up.

As the stage always stopped at every inn, so the trains would

come to a halt whenever they passed in sight of one. All hands—engineer,

firemen, trainmen, and passengers—would alight and trudge

across the field, leaving the train deserted on the main line

until the thirst and appetites of all were satisfied.

Each inn carried the fundamental necessity of life in the thirties,

to wit, whisky, of course; but in addition each had its own particular

specialty by which its fame was spread among travelers.

At one place it would be coffee and big, fat doughnuts; at

another, apple-pie with milk; at another, waffles and fish; at

still another, chicken fricassee or beer and gingerbread, and

so on. To any one not dyspeptic nor in haste, therefore, a trip

over the Philadelphia and Columbia Railroad was one prolonged

delight.

This happy-go-lucky method of operating the road at last grew

intolerable. The Board of Canal Commissioners then took the advanced

step of prescribing hours when locomotives might use the road.

The order was that locomotives might leave the top of the Belmont

Plane, which was at the Philadelphia end, only between the hours

of 4 and 10 A.M. and 5 and 8 P.M., the last to leave carrying

a signal to indicate that fact.

This left a period of seven hours during the day and eight

hours at night free for the use of horses. Beyond this, rules

for running were conspicuous by their absence.

There was a continual conflict between individual transporters

who wished to use horses and the Board of Canal Commissioners,

who wished to use steam and control the movement of trains. Finally

the Board took the bull by the horns and prohibited the use of

horses on the railroad after April 1, 1844.

Meanwhile improvements were being made in methods of railroad

operations. A great advance in carrying mail and baggage was made

when "Possum Belly" cars were introduced. The "Possum

Belly" car had a huge box or cellar beneath the floor of

the car into which mail-bags, portmanteaus, and bundles could

be thrust.

Sam Jones, known to the traveling public as " Grubey Sam,"

a deformed negro, the first of his race to be employed on a railroad

in the State, had charge of the "Possum Bellies," and

he was fully aware of the dignity and importance of his position.

But he was bright, faithful, and alert, so he made more friends

than. enemies.

Locomotives necessitate shops; so as soon as the first batch

of twenty engines had been ordered a site was chosen for the first

railroad shops in Pennsylvania. The location chosen was in a field

midway between Philadelphia and Columbia. One reason for this

was that John G. Parke, a wealthy and influential man, was aggrieved

because he was unable to collect a claim of $3,273 for damages

sustained by reason of the road passing between his house and

his barn.

For political reasons the Board could not afford to incur his

enmity, so they accepted his offer of a site, laid out a town,

and called it Parkesburg. Work on the first shop was begun December

4, 1833.

But another important reason for locating the shops in the

country was to spare the shopmen the corrupting influence of the

engineers. In those days enginemen were hard to get, and the Board

had to wink at peccadilloes that would not be passed over so lightly

now.

At these shops safety chains were first put on between engine

and tender, because an engine while on the road broke away from

its tender, spilling the fireman and engineer to the ground between

the rails, where both were torn to pieces.

The "Grasshopper level," four miles from Lancaster,

was responsible for another important improvement in locomotives.

The place was so called because one summer the grasshoppers were

so thick in the vicinity that they wore the fence rails smooth

passing from field to field in search of food. Also, they were

so thick on the rails that the locomotive wheels slipped on their

crushed bodies and the trains were stalled.

Edwin Jeffries, the manager of the Parkesburg shops, sent out

men to pour sand on the rails so the locomotives' driving-wheels

could take hold. This suggested putting a box of sand on the front

end of the locomotive for the convenience of the men. Then the

box was placed on top of the boiler, with pipes running from the

box to the rails in front of the drivers, and a valve in the pipes

which could be operated by the engineer. Thus was evolved the

sand-box of to-day, and also that favorite story, ever on its

travels, about the grasshoppers stopping the train.

Jeffries also conceived the idea of putting cabs on the engines,

but the men at first refused to ride in them. They were afraid

of being trapped in case of an upset, and the fear was not groundless.

The rails were laid in chairs on stone blocks, and held in

place by wedges. Of course, the wedges were forever working loose

and permitting the rails to spread. Derailments were of frequent

occurrence, particularly in bucking snow.

In spring when the frost was coming out of the ground, heaving

the tracks in all sorts of kinks, several trains a day would be

off the rails.

There were no telegraph, no telephone, no block-signals, nor

even any headlights on the engines. The first intimation of a

wreck would be the arrival of a messenger on a farmer's horse.

A wrecking-crew was kept constantly in readiness at each end of

the line and at Parkesburg.

Experience taught in due time that it wasn't always necessary

to wait for the arrival of a messenger with news of disaster.

If a train didn't show up when it should the wrecking-crew would

start out in search of the derelict, with two men riding on the

front end of the locomotive, who would take turns in sprinting

ahead with a red light around curves as a precaution against an

additional wreck.

While the Philadelphia and Columbia Railroad was being built,

good progress was being made on the Alleghany Portage Railroad.

One track of this remarkable road was opened November 21, 1833,

and early in the spring of 1834 a double track was completed and

the road was ready for traffic.

When the engineers in laying out a railroad came to a hill

they could not go around they laid a line of rails straight up

the slope, called it an inclined plane, and placed a stationary

hoisting engine at the top to haul the cars up. Even the Philadelphia

and Columbia Railroad had an inclined plane at the Philadelphia

terminus on the banks of the Schuylkill, with a length of 2,800

feet and a rise of 196 feet, and another at Columbia 1,800 feet

long, with a rise of 90 feet. The heaviest grade on the road was

forty-four feet to the mile.

Engineers took it for granted that locomotives could only travel

on practically level track, just as they had previously taken

it for granted that the driving wheels of a locomotive or a steam

road carriage would revolve impotently on the rail or on the ground

without moving forward.

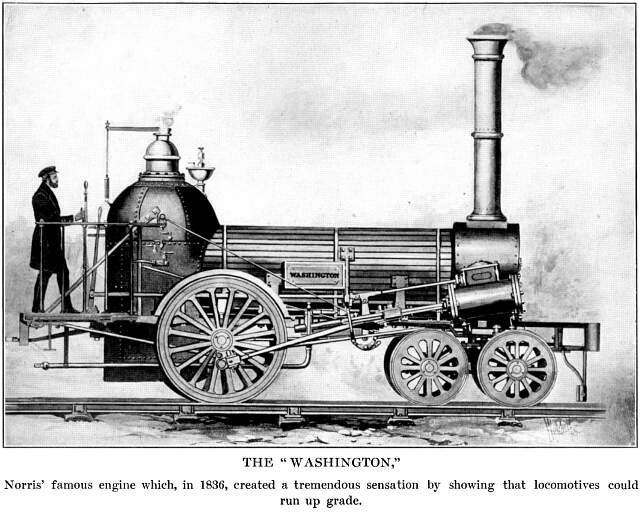

But William Norris, a brilliant and energetic young locomotive

builder of Philadelphia, Baldwin's most formidable rival, built

a locomotive in 1836 which he named the "Washington"

of the remarkable weight of fourteen thousand four hundred pounds.

It had cylinders ten by eighteen inches and a single pair of drivers

forty-eight inches in diameter. The boiler carried the heavy pressure

of ninety pounds of steam.

This prodigy performed so well on its trial trip that Norris,

who always was regarded as a reckless person, decided to see what

it would do on the inclined plane at Philadelphia, on a grade

of three hundred and sixty-nine feet to the mile. To his unbounded

delight the Washington puffed its way steadily to the top of the

plane. No one would believe Norris when he told what the new locomotive

had done. They said his tale was a fabrication on the face of

it, since it was perfectly obvious that a locomotive simply could

not ascend an inclined plane solely by its own power. Even after

the feat had been repeated in the presence of many witnesses it

could scarcely be credited. Eight months after Norris had demonstrated

that a locomotive could not only climb an ascending grade by its

own power, but could also haul a train up, A. G. Steere, of the

Erie Railway, in a long communication to the Railroad Journal

of March 11, 1837, proved by elaborate algebraic formulae

that the Washington did not climb the hill, because it could not;

and that no other locomotive ever could climb an ascending grade

by its own power. Mr. Steere was very nice about his exposure

of Mr. Norris' alleged "deeds done in flagrant and open violation

of the laws of gravitation." He explained the motives which

led him to show up the preposterous claims as follows:

"Accounts of the very wonderful feats

said to have been performed by Mr. Norris' engines on the Columbia

Railroad have not been noticed by scientific men from the fact,

I suppose, that the errors in them were so enormous and apparent

that they supposed they would be detected by all and were, therefore,

not worth exposing. But the mass of those who read these accounts,

now again put forth as facts, and who are interested in railroad

improvements are not scientific men; and it is to prevent such

from daily quoting and swallowing absurdity with such grave astonishment

that I send you the following exposition. I have not the least

desire to prejudice the community against Mr. Norris' engines,

which, 1 have no doubt, are really very superior ones, but I do

not wish capitalists to mistake steep roads for cheap ones or

to suppose engines are going to draw loads which are really impossible

for Mr. Norris' engines or any others."

This was the opening gun in a long and earnest discussion in

the columns of the Railroad Journal concerning the possibility

or the impossibility of an engine climbing a hill. It was rather

difficult, however, to maintain that a thing could not be done

when it was being done daily, and the controversy finally died

out.

As the real development of the railroad dates from the astounding

discovery that locomotives could haul trains uphill, the following

contemporary account from the Railroad Journal of July

30, 1836, of a trial trip made by Norris with his locomotive Washington

at the request of D. K. Minor, the editor of the Journal, may

be of interest:

"In pursuance of our request Mr. Norris

made arrangements with the Commissioners of the Columbia Railroad

for the use of his locomotive. Tuesday, July 19 [the first trial

had been made on July 9 when the Washington ascended the plane

with a trainload of 19,200 pounds in 2 minutes and one second],

was the day appointed for the trial.

"We left New York Monday afternoon at 4 o'clock, accompanied

by Mr. George N. Miner, of New York; Theo. Schwartz, of Paris,

and Messrs. Elliot and Betts, of Alabama. Mr. Schwartz, who was

to sail to Europe next day, gladly made the trip with a view to

carrying home his testimony as an eye witness. Our journey over

the Camden and Amboy and Trenton and Philadelphia Railroads was

highly interesting and the conversation of the evening will long

be remembered with pleasure. We arrived at Philadelphia about

midnight, and after sundry mistakes and mis-chances succeeded

in obtaining some repose.

"On Tuesday morning two cars drawn by horses set out with

a party of upwards of forty. We arrived at the foot of the inclined

plane before 6 o'clock while the rails were yet quite wet with

the dew. On our arrival it was found that by accident or design,

while the fire was burning the water had been blown out of the

boiler so as to endanger the tubes. The result was a leakage of

some consequence during the day.

"The engine started at the foot of the plane and on the

plane. After proceeding a few feet the wheels were found to slip

and the engine returned. It was said that the rails were found

to have been oiled at this place; but a small quantity of sand

was strewn on the spot and the engine proceeded. She regularly

and steadily gained speed as she advanced to the very top, passing

over the plane in 2 minutes and 24 seconds.

"The enthusiasm of feeling manifested cannot be described.

So complete a triumph had never been obtained. The doubts that

had been entertained by some and the fears of others were dispelled

in an instant. The eager look that settled upon every one's face

gave way to that of confident success while all present expressed

their gratification in loud and repeated cheers.

"The length of the plane is 2,800 feet; the grade 369

feet to the mile, or 1 foot rise in 14.3 feet, which is a much

steeper grade than the planes on the Mohawk and Hudson Railroad,

those being I foot in 18, making an ascent of 196 feet in 2,800.

The weight of the engine with water was 14,930 pounds; the load

drawn up the plane, including the tender with coal and water,

two passenger cars with 53 passengers, was 31,270 pounds; steam

pressure less than eighty pounds to the square inch; time of run

2 minutes, 24 seconds. It is to be remembered that the rails were

wet with dew. As to the oil, it was afterwards mentioned that

bets were made with the workmen to a considerable amount and those

having been lost by the successful performance of the engine on

a former day were quadrupled, and to save themselves it is not

unlikely that this means was provided to accelerate the descent

rather than the ascent of the engine.

"The party again embarked after examining the workshops

and proceeded to Paoli for breakfast and thence to Lancaster,

the engine conveying at the same time a number of freight cars.

The unfortunate location of this road is very evident; frequent

and short curves are introduced so uniformly that it would be

supposed that such a location was to be preferred to a direct

one.

"We arrived at Lancaster and partook of an excellent dinner.

After dinner the company were presented to Governor Ritner, who

was then in town. He afterwards accompanied the party some few

miles from Lancaster when he left us much gratified with his rapid

journey. We returned in an eight-wheeled car, a form that we much

admired. The whole weight attached to the engine, tender and so

forth included, must have been over fourteen tons. The time of

the run, exclusive of stoppage, from Lancaster to the head of

the Schuylkill inclined plane, was 8 hours, 11 minutes, being

a distance of 76 miles. This, it is to be remembered, was over

a road having curvatures of less than six hundred feet radius,

up ascents of sometimes 45 feet to the mile. On level and straight

portions of the road a velocity of forty-seven miles an hour was

attained. As the trip had already been protracted this engine

was obliged to leave on her return to Lancaster the same evening

and we descended by the rope. We returned to the city about 8

o'clock in the evening convinced of the success of our host, Mr.

Norris, and having in the language of one of our party 'lived

six days in one.'

"The following are the dimensions of the George Washington

engine of William Norris: diameter of cylinders, 10 1-4 inches;

length of stroke, 17 5-8 inches; number of tubes, 78; outside

diameter of tubes, 2 inches; length of tubes, 7 feet; diameter

of driving wheels, 4 feet; diameter of truck wheels, 30 inches;

whole weight of engine, 14,930 pounds; actual weight on drivers,

8,700 pounds. It must be remembered that there is no contrivance,

as in some engines, for increasing the adhesion by throwing the

weight of the tender upon the engines, the axle being in front

of the firebox, preventing any such arrangement. This engine,

we are informed, is making the regular trips, though a full load

has not yet been obtained on account of a scarcity of cars. The

greatest load as yet drawn by it over the road was one hundred

and nineteen tons gross weight in twenty-two cars."

This account was accompanied by a certificate signed by fifty-three

passengers attesting the fact that they had actually been drawn

up the inclined plane as described. Soon afterward Norris built

the "Washington County Farmer," weighing 18,170 pounds,

for the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, which was tested on the

same plane, according to the National Gazette of October

19, 1836, "to the complete satisfaction of numerous

scientific gentlemen invited expressly for the occasion."

The time required for the ascent was 3 minutes and 15 seconds.

In descending, the engineer, according to the same authority,

repeatedly "came to a dead stand from a great speed, and

for some minutes played up and down the grade, thus proving most

satisfactorily the great power of the engine and the perfect safety

in its performance. The engine is a masterpiece of machinery and

of beautiful exterior. The result here obtained has never been

equaled by the best engines in this country or Europe, excepting

only similar performances of the George Washington engine by the

same maker. The advantage of this great improvement in locomotives

is self-evident. Railroads can be constructed at much less cost

than heretofore now that engines can be procured to perform on

grades of seventy feet or even a hundred feet rise in the mile."

So little did the general public understand what a locomotive

could do or should be that a genius named French actually induced

the legislature of Virginia to appropriate a sum of money as late

as 1850 to make a practical test of his locomotive for wooden

railroads. French had observed that wooden rails would not answer

the purpose because the weight of the locomotives broke and splintered

them. As he was convinced that wooden rails were much better than

iron, and as he had found that beech and maple rails would last

five years or more under favorable conditions, the problem was

to adapt the locomotive to the rails and not the rails to the

locomotive. He did this by means of horizontal driving wheels,

which, by means of a lever, were made to grip a wooden third rail

in the middle of the track. As these horizontal driving wheels

held the locomotive on the track, the necessity for flanges on

the wheels was thus done away with and another source of destruction

to wooden rails avoided. George E. Sellers, of Cincinnati, also

invented a "gripping" locomotive that found many advocates.

An equally brilliant design for cars that could not upset was

evolved by one Lawrence Meyers, of Pottsville, Pa., a year later.

It was alleged that the Meyers car won the approval of President

John Tucker, of the Reading Railroad. Meyers' car consisted of

a cylinder of wrought iron 42 inches in diameter, on each end

of which a wheel 52 inches was riveted so that it would roll along

the track. The cylinder was to be filled with coal, of which it

would hold two tons. Several of these cylinders being connected

by means of a wooden frame were to constitute a "Revolver

train."

When it came to passing the Alleghanies, the engineer laid

out a succession of ten inclined planes with "levels"

between, on which the grades were not heavy enough to require

the employment of a hoisting engine and cable. The total length

of the Portage road was thirty-six miles.

The summit was 1,398 feet above the eastern canal basin, and

1,171 feet above the western, and 2,326 above sea-level. The longest

of these planes was 3,116 feet, and the rise was 307 feet. The

most conspicuous features of the road were the Conemaugh Viaduct,

eight miles east of Johnstown, which was destroyed by the great

flood of May 31, 1889, and the Staple Bend tunnel, nine hundred

feet long, four miles east of Johnstown. This was the first tunnel

built in America.

The engines for operating these planes had two cylinders fourteen

inches in diameter by sixty inches stroke, made fourteen revolutions

a minute, and at a steam pressure of seventy pounds developed

about thirty-five horse-power. They hauled cars up the planes

at the rate of four miles an hour, by means of ropes eight inches

in diameter and from 3,316 feet to 6,662 feet long. These ropes

were the cause of considerable outlay, since they cost on an average

three thousand dollars and lasted only about sixteen months.

Toward the last John A. Roebling, the great bridge builder,

induced the Board of Canal Commissioners to experiment with wire

cable. The first trials were not satisfactory, but a little investigation

showed how to overcome all difficulties, and then wire displaced

hemp.

To run each of these planes required an engineer at $2.00 a

day, a fireman at $1.12½, and a man at top and bottom at

$1.00 per day to attach and detach the cars. On reaching a level,

horses or a locomotive would be attached and the cars hauled to

the next level on a road laid with malleable iron rails imported

from Wales.

The use of horses was found wasteful, expensive, slow, and

unsatisfactory, so before the second track was finished the Board

had ordered a first installment of a couple of locomotives. But

the use of horses by individual transporters continued until 1850,

with the same results as on the Philadelphia and Columbia Railroad.

No two teamsters wanted to start at the same time, and no two

were willing to stop at the same place to feed. These teamsters

were an exceedingly difficult lot of men to handle. They were

rough, quarrelsome, stubborn, and unmanageable, fearing neither

man nor fiend. It was impossible to get them to regulate their

movements by a time table. The officers of the road had no power

to discharge them or keep them off the road, so they worked their

own sweet will, for was not the railroad a public highway provided

by the State, and were they not as good citizens as any other

man, if not better?

It sometimes happened that a teamster would get stalled so

that he could not go forward. Being too stubborn to go back, he

would stay where he was, blocking the entire road, perhaps for

hours, until a better man came along and thrashed him into a reasonable

frame of mind. Theoretically an unruly teamster could be arrested

for obstructing the railroad and taken before a magistrate, who

might fine him. But as the magistrates were miles away, and an

arrest meant a fight first, such extreme measures were not often

resorted to.

When the road was first opened it had but a single track. In

order to keep it in operation at all it was necessary to set up

center posts half-way between turnouts and make a rule that the

man who passed the center post had the right to proceed in case

of meeting a team going in the opposite direction, which would

have to go back to a turnout. This caused the drivers, who were

always reluctant to turn back, and never did so if they could

bully the other fellow who had the right of way into doing so,

to start slowly in leaving a turnout so they might not have to

return so far. As they proceeded they would increase their speed

until by the time they reached the center post the horses would

be going at a wild gallop, with drivers plying the lash, shouting,

and swearing. Sometimes cars collided near a center post while

going at high speed, wrecking both cars and tying up traffic until

the wreckage could be cleared away. In one of these collisions

a man was killed.

Even after the road was double-tracked the situation became

so intolerable that S. W. Roberts, the chief engineer, determined

to have conditions changed if possible. A change could only be

brought about by legislation, which was not easy to obtain. The

State was Democratic, and the methods then in use of allowing

every man to do as he pleased were considered to be the popular

way to operate a railroad. The proposal to exclude private transporters

from the Portage Railroad and operate it by the State met with

the most vehement opposition, both from the public and the legislature.

Roberts finally had his way when he won Thaddeus Stevens, who

bossed the Pennsylvania legislature as he afterwards did Congress,

to his view of the way a railroad should be operated. The average

load on the cars was six thousand pounds, and the cost of moving

freight over the Portage road averaged ninety-six cents a ton.

Five minutes were consumed in going up or down the longest plane,

and three minutes more were required to attach and detach the

cars.

The limit of capacity was five hundred and seventy-six cars

one way in twenty-four hours. In the six months ending October

31, 1836, 19,171 passengers and 37,087 tons of freight passed

over the Portage road.

Charles Dickens made a trip over the Portage road in 1842,

and was delighted with the experience, which he describes in his

"American Notes." But, then, Dickens was not accustomed

to Pullmans. If he had been, he would hardly have been enraptured

with a journey that consumed seven hours in traversing thirty-six

miles.

With the Portage road open it was possible to make the journey

of 395 miles from Philadelphia to Pittsburg, on public works,

118 miles being by rail and 277 on canals, in 91 hours, or an

average of 4.34 miles an hour. The fare was fifteen dollars. In

both time and expense even this was a decided advance on the stage

coach, which required seven days to make the trip, and cost the

passenger twenty dollars for fare and eight dollars and twenty-one

cents for meals en route. For twenty years the Pennsylvania Public

Improvements were an important trade route.

Some time after the Portage road was opened an emigrant, who

had loaded his family and all his earthly possessions on a boat

on the Susquehanna, arrived at Hollidaysburg on his way to Missouri.

He was going to sell his boat and continue his journey as best

he could; but the accommodating superintendent of the Portage

Railroad told him to wait a minute, and he'd see what he could

do.

In a couple of hours he had rigged up a sort of cradle on a

couple of cars, which were run into the water under the boat.

The latter was fastened to the cars, which were attached to the

cable, and away went boat, emigrant, and all over the mountains.

In due time the boat was deposited in the canal at Johnstown.

This incident led to the building of canal boats in sections

and of trucks to transport the sections over the mountains, thus

avoiding the expense and delay of breaking bulk on each side of

the mountains. To move one of these sectional boats over the mountains

required the services of twelve stationary engines, twelve different

teams of horses, nine locomotives—thirty-three changes of

power in thirty-six miles—and fifty-four men.

While this line from Philadelphia to Pittsburg was being constructed,

the link which was to extend the line to New York was being evolved

out of a chaos of conflicting interests and financial difficulties.

New Jersey was just as much wrought up over the relative merits

of canals and railroads as any other commonwealth.

In fact, it reached a point in the winter of 1829-1830 at Trenton

when partisans of either side were afraid to venture out after

dark unarmed. The legislature poured oil on the stormy waters

by chartering simultaneously the Camden and Amboy Railroad and

the Delaware and Raritan Canal to open communication between Philadelphia

and New York.

In order that the companies might be able to offer inducements

to capital the legislature granted each a monopoly in its own

line of construction.

Grading on the railroad was begun at Bordentown, December 1,

1830. That made the canal people jealous, and in spite of all

pledges to keep to their own specialty they insisted on building

a railroad also. There was another battle of the lobby at the

legislative session of 1830-1831, which was so virulent as to

endanger the existence of both companies.

This contest also ended in a compromise by which the two companies

were merged under the famous "marriage act " of February

15, 1831.

Enough track was laid to enable the company to give an exhibition

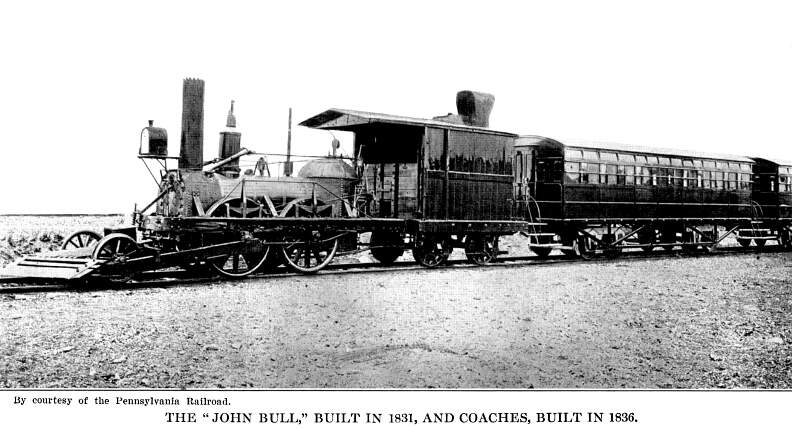

trip November 12, 1831, behind one of the many John Bull locomotives,*

which were almost as numerous as Washington's headquarters. The

first woman who ever rode on a railroad on New Jersey soil was

a guest on this occasion. She was Mme. Murat, wife of Prince Murat,

Napoleon's nephew.

* Of the numerous "John Bull" locomotives, this

one, the oldest complete locomotive in America, has at last come

to be known as the John Bull. It is not a model nor a reproduction

but the original engine. The picture below is from a photograph

made at the World's Columbian Exposition in 1893.

Originally the John Bull was locomotive No. 1 built by Stephenson

& Co. in 1830-1 for the Camden and Amboy Railroad, now a part

of the Pennsylvania system. It was shipped from Liverpool July

14, 1831, and made its first trip in regular service November

12, 1831.

The John Bull and its train was exhibited at the Centennial

Exposition in Philadelphia in 1876. On April 17, 1893, the engine

with train, as shown in the picture, left New York City under

its own steam and made the run of 912 miles over the Pennsylvania

Railroad to Chicago, meeting with a continuous ovation throughout

the trip, and arriving April 22. It was one of the greatest attractions

at the World's Fair, carrying thousands of passengers over the

exhibition tracks in the Terminal Station yard. The locomotive

left Chicago under its own steam again December 6, 1893, going

over the Pennsylvania system by way of Harrisburg and Baltimore

to Washington. Having made its last trip under steam it was returned

to the United States National Museum to remain there permanently.

The two Camden and Amboy coaches shown are of the model

of 1836. One is the original car, the body of which was used as

a chicken coop at South Amboy, N. J., for many years.

Mme. Murat was the daughter of Colonel Frazier, a Scotch officer

who, while serving in the British army in the Revolution, fell

madly in love with a beautiful Virginia girl, and returned and

married her as soon as he could give up his commission.

The directors of the New Jersey Railroad and Transportation

Company issued an address on January 1, 1839, in which they congratulated

themselves and the public on the opening of an all-rail line from

Camden to Jersey City, by which it was possible to go from Philadelphia

to New York in six or seven hours with almost as much comfort

as the traveler could have at his own fireside, whereas the journey

had formerly required eleven to twenty hours, and had been made

at the expense of great discomfort and even hazard to life.

Another important link in the State system of railroads, destined

later to become a part of the great Pennsylvania system, was the

Cumberland Valley Railroad, which was formally opened from Harrisburg

to Chambersburg, Thursday, November 16, 1837. A double-header

was run over the road to accommodate the great number of guests.

Shouts of welcome greeted the train at every revolution of

the wheels. The people were wild with delight. Here is the way

the Carlisle Republican described the trip of that first

train:

"Dogs dropped their tails between their

legs and ran like frightened fiends, howling and trembling, to

the far-of mountains. Men there were who cleared ditches and fences

at a single bound as the hissing engines approached. Others rolled

on the ground and cracked their heels together to express in a

new way a new delight.

"Old men and women leaned on their staffs and gazed in

visible awe as if doomsday were at hand. Blooming maidens I capered

and danced and looked with more delight on the grim and besooted

countenance of the steam demon than ever they did on clean-washed

lovers dressed in Sunday clothes."

While the Board of Canal Commissioners was publishing assurances

that the system of canals and railroads built under its direction,

at an expenditure of nearly twenty million dollars, placed Pennsylvania

on an eminence where there could be no apprehension of rivalry

from sister States, the people were growing more and more dissatisfied.

The management of the State railroads and canals had become

a public scandal. The paymaster openly counted out ten per cent

of the wages of the employees, which he tossed into a bag at his

side labeled "political assessments." Gravel trains

loaded with men were run over the road on election day, the men

getting off at every town and voting.

The public service was fairly swamped with employees whose

chief duties were to draw their salaries and vote. Transporters

who refused to do the bidding of the party in power were ruined,

while the more complaisant received rebates equal to the amount

of the tolls they had paid.

The pass system originated in Pennsylvania under State ownership

of the railroads. At first the State officials claimed the right

to travel over the State highways free of charge. Then county

officials claimed the same right, then politicians were unable

to see why they should pay, and so it went on until more deadheads

than paying passengers were being carried.

Thaddeus Stevens, who had been so apprehensive of the dangers

of putting locomotives on the State railroads on account of the

patronage they would place in control of the party in power, on

being made chairman of the Board of Canal Commissioners at once

proceeded to demonstrate that his fears were well founded.

He owned some iron lands in the southern part of the State

to which he undertook to build a railroad, which was so wildly

impracticable and so devious that it is known in history as "Stevens's

tapeworm." He spent three-quarters of a million dollars of

State money on it before he was deposed, not one dollar of which

was ever of any earthly benefit to the State.

But the worst of it all was that the State was not reaping

the commercial benefits expected. In addition to mismanagement

the canals were frozen over and useless in winter. Philadelphia,

as well as other parts of the State, was steadily falling behind.

A mass-meeting was held in the Chinese Museum building, Philadelphia,

December 10, 1845, at which a memorial was prepared asking the

legislature to charter a private railroad corporation to build

a railroad system that would be up with the times.

There was a savage fight in the legislature that winter, for

the Baltimore and Ohio wanted to build to Pittsburg, and the people

of the southern and western parts of the State, who felt that

they had been badly treated by the State Board, favored the Baltimore

and Ohio project.

The outcome was a charter for both roads, but the Governor

was authorized to give preference to the Pennsylvania Company

if it should have one million dollars in the treasury and thirty

miles under contract by July 30, 1847, by annulling the charter

of the Baltimore and Ohio.

The Pennsylvania Railroad Company was organized March 31, 1847,

and J. Edgar Thomson, son of the man who had built the little

wooden railroad thirty-eight years before, was made chief engineer

and general manager. Ground was broken for the Pennsylvania Railroad

at Harrisburg, its eastern terminus, July 7, 1847. Connection

was made with the Portage Railroad, November 1, 1850.

Trains were run from Philadelphia to Pittsburg, December 10,

1852, by the Philadelphia and Columbia Railroad and the Alleghany

Portage Railroad. A line through the mountains, to cut out the

Portage road, was not completed till February 2, 1854.

As soon as the engineering difficulties were solved and the

construction department was running smoothly, Thomson was called

to the president's chair to create an effective working organization.

Mr. Thomson was a man of splendid physique and a tireless worker.

He talked little, but was a good listener. Above all, he had the

gift of selecting the right man to do a given task.

A remarkable example of this is shown in his choice of a man

to establish that discipline and esprit de corps for which

the Pennsylvania Company is so famous that to this day it is held

up as the apotheosis of all that is desirable in a railroad staff.

This work fell upon General A. L. Roumfort, who was born in

Paris, educated at West Point, had conducted a military school

in which some of the most prominent men of their time were educated,

had been a member of the legislature for several terms, and finally

had filled the position of superintendent of the Philadelphia

and Columbia Railroad. He was six feet tall and built in proportion.

He had a military bearing and dignified manner.

His first task was to create an orderly baggage system out

of the chaos at Aqueduct and Harrisburg. During the spring freshets

swarms of raftsmen passed over the road, leaving at Aqueduct to

proceed up the Susquehanna. They were rough, boisterous, and lawless.

Their baggage consisted of stoves, pots, pans, rope, carpet-bags,

bundles of clothing, and provisions and chests.

General Roumfort's appearance commanded respect and obedience.

He established order at Aqueduct and he created system where confusion

had reigned in the baggage department. He attempted to uniform

the trainmen. Passenger conductors were required to appear in

blue cutaway coats with brass buttons, buff vests, and black trousers,

and passengers brakemen in gray sack suits; but the plan was not

popular and when the first suits wore out they were not replaced

until the Civil War had earned respect for uniforms.

General Roumfort's favorite seat in fair weather was on a corner

of the second-story porch of the old station at Harrisburg, where

he could hear the whistle of the approaching trains.

There was a bell in a little tower on the top of the depot,

which was rung to announce the arrival and departure of trains.

As soon as the whistle was heard General Roumfort's sonorous voice

would wake the echoes.

" Billie! O Bil-lie! Ring that bell."

When the "tub," the first through train between Harrisburg

and Philadelphia, was put on, the general sent for William Wolf

and Benjamin Kennedy, the engineers who were to take the run.

Both men were undersized. The general thus addressed them

"Now, boys, you are going to run through to Philadelphia

over a strange road. When you leave Columbia you will have a steep

grade to Mountsville. See that you have a good supply of water

in the boiler. Also instruct your firemen to have in a good fire

for the Gap grade.

"When you reach Downingtown instruct your firemen to have

a good fire for the Byers hill, thirteen miles to Paoli. Now,

you two little engineers, run along to your two little engines

and see that you make time."

The choice of Thomas A. Scott as superintendent of the western

division was equally felicitous. The road was not finished to

Pittsburg when Scott took up his duties there. Pittsburg had wanted

the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, and the city had waxed extremely

hostile when that road's charter had been annulled.

But Scott handled the situation with such consummate diplomacy

that he not only allayed all animosity but actually secured one

million dollars for the Pennsylvania and many valuable franchises

and privileges besides.

Diplomacy was quite as much needed as engineering skill in

the first stages of the Pennsylvania Railroad. At first the company

was not permitted to run its trains over the Philadelphia and

Columbia Railroad. When it was granted this boon it could not

run its own comfortable cars, because the tracks were too close

together, and the roof of the Elizabethtown tunnel was too low.

Individual transporters were still doing business on the State

road, and their operations sadly interfered with the development

of the transportation business the new road needed. But too radical

or too sudden a change would have aroused public opposition which

would have been disastrous.

The difficulty was solved by the purchase of the main line

of the public works by the Pennsylvania Railroad Company for seven

million five hundred thousand dollars, possession being given

by the State August 1, 1857. The first through train from Philadelphia

to Pittsburg without transfer of passengers was run July 18, 1858.

On the same day smoking-cars were first run on through trains

and Woodruff's sleeping-cars on the night trains.

The Pennsylvania Railroad was now fully launched. Its development

was so rapid that when the Civil War began, three years later,

it was in a position to do the nation a great service, not only

on its own rails, but also by supplying skilled and disciplined

executive and operating men to the Government.

December 1, 1871, it acquired by lease for nine hundred and

ninety-nine years the line to Jersey City, and six years later

had a double track in operation across the State of Pennsylvania.

It had long since acquired lines to Chicago, St. Louis, and the

Central West, the westward extension being greatly accelerated

through the kind assistance of Jay Gould. It cannot be truthfully

said, though, that the Pennsylvania was at all grateful to the

great manipulator.

The Pennsylvania had been encouraging by financial assistance

and otherwise the development of a chain of little railroads between

Pittsburg and Chicago, which was afterwards welded into the Pittsburg,

Fort Wayne and Chicago. The Pennsylvania, however, was satisfied

with a traffic arrangement and did not attempt actual possession.

When Gould, after establishing himself as the master of the

Erie, began reaching out right and left for every railroad property

that was lying around loose, other managements were thrown into

a panic. Before the Pennsylvania could recover its self-possession

sufficiently to profit by the object lesson Gould had given, that

astute operator had secured possession of a majority of the stock

of the Pittsburg, Fort Wayne and Chicago. An election for directors

was to be held in March, 1869, when he would have established

himself securely in the management of a line that was absolutely

essential to the continued prosperity of the Pennsylvania, had

not that road established a world's legislative record by securing

the passage of a bill by both houses of the Pennsylvania legislature

and its signature by the Governor in thirty-four minutes by the

clock on February 3, 1869. This was the famous "classification

bill," which divided the board of directors of the Fort Wayne

road into three classes in such a way that it would require three

years to elect a majority. This was too slow for Gould, and he

withdrew. After such a narrow escape the Pennsylvania lost no

time in securing its Western extension against the possibility

of any such embarrassing complications in future.

The same zeal was displayed in adopting improvements and in

extending the system and perfecting organization. The Pennsylvania

Railroad was the first to use steel rails, in 1863; the first

to use Bessemer steel rails, in 1865; the first to adopt the air-brake,

in 1866; the track tank, in 1872, and the signal block-system,

in 1873.

When the semi-centennial of the company was celebrated in Philadelphia,

April 13, 1896, President Roberts was able to report as a net

result of all these endeavors that the Pennsylvania Railroad comprised

138 separate railroads, representing what were originally 256

separate corporations with 9,000 miles of main line having an

aggregate capital of $834,000,000, an army of 104,000 employees,

who received $59,000,000 in wages annually, and that the company,

in its existence of fifty years, had paid $166,000,000 in dividends.

Pennsylvania

Page | Antebellum RR Page | Contents Page

|