from The History of the Lackawanna Valley

by H. Hollister, M. D.—1869

THE PENNSYLVANIA COAL COMPANY.

The definite and successful character of the coal schemes devised

by the Wurts brothers, tested amidst every possible element of

discouragement and hostility, inclined capitalists to glance toward

the hills from whence coal slowly drifted to the sea-board. Drinker

and Meredith, aiming at reciprocal objects, and alive to venture

and enterprise, each obtained a charter for a railroad in the

valley, which, owing to the absence of capital, proved of no practical

value at the time to any one.

Twenty-one years after coal was carried from Carbondale by

railroad toward a New York market, the Pennsylvania Coal Company

began the transportation of their coal from the Lackawanna. This

company, the second one operating in the valley, was incorporated

by the Pennsylvania Legislature in 1838, with a capital of $200,

000. The proposed road was to connect Pittston with the Delaware

and Hudson Canal at some point along the Wallenpaupack Creek in

the county of Wayne.

The commissioners appointed in this act organized the company

in the spring of 1839, and commenced operating in Pittston on

a small scale. After mining a limited quantity of coal from their

lands—of which they were allowed to hold one thousand acres—it

was taken down the North Branch Canal, finding a market at Harrisburg

and other towns along the Susquehanna.

Simultaneously with the grant of this charter, another was

given to a body of gentlemen in Honesdale, known as the Washington

Coal Company, with a capital of $300,000, empowered to hold two

thousand acres of land in the coal basin. This last charter, lying

idle for nine years, was sold to William Wurts, Charles Wurts,

and others of Philadelphia, in 1847.

In 1845, the first stormy impulse or excitement in coal lands

went through the central and lower part of the valley. Large purchases

of coal property were made for a few wealthy men of Philadelphia,

who had reconnoitered the general features of the country with

a view of constructing a railroad from the Lackawanna to intersect

the Delaware and Hudson Canal near the mouth of the Paupack.

The preliminary surveys upon the proposed route had barely

commenced, before there sprang up in Providence and Blakeley,

opposition of the most relentless and formidable character. Men

who had hitherto embarrassed the company mining coal in Carbondale

during its infancy, found scope here for their remaining malignity.

The most plausible ingenuity was employed to defeat the entrance

of a road whose operations could not fail to inspire and enlarge

every industrial activity along its border. Meeting after meeting

was held at disaffected points, having for their object the destruction

of the very measures, which, when matured, were calculated to

result as they did to the advantage of those who opposed them.

It was urged with no little force, that if these Philadelphians

"seeking the blood of the country," were allowed to

make a railroad through Cobb's Gap, the only natural key or eastern

outlet to the valley, the rich deposits of coal and iron remaining

in the hands of the settlers would be locked in and rendered useless

forever. Such fallacious notions, urged by alms-asking demagogues

with steady clamor upon a people jealous of their prerogatives,

inflamed the public mind for a period of three years against this

company, but after such considerations as selfish agitators will

sometimes covet and accept tranquilized opposition, those amicable

relations which have since existed with the country commenced.

In 1848, the Legislature of Pennsylvania passed "an act

incorporating the Luzerne and Wayne Railroad Company, with a capital

stock of $500,000, with authority to construct a road from the

Lackawaxen to the Lackawanna."

Before this company manifested organic life, its charter, confirmed

without reward, and that of the Washington Coal Company being

purchased, were merged into the Pennsylvania Coal Company, by

an act of the Legislature passed in 1849.

This road, whose working capacity is equal to one and a half

million tons per annum, was commenced in 1848; completed in May,

1850. It is forty-seven miles in length, passing with a, single

track from the coal-mines on the Susquehanna at Pittston to those

lying near Cobb's Cap, terminating at the Delaware and Hudson

Canal at the spirited village of Hawley. It is worked at moderate

expense, and in the most simple manner for a profitable coal-road—the

cars being drawn up the mountain by a series of stationary steam-engines

and planes, and then allowed to run by their own weight, at a

rate of ten or twelve miles an hour, down a grade sufficiently

descending to give the proper momentum to the train. The movement

of the cars is so easy, that there is but little wear along the

iron pathway, while the too rapid speed is checked by the slight

application of brakes. No railroad leading into the valley makes

less noise; none does so really a remunerative business, earning

over ten per cent. on its capital at the present low prices of

coal; thus illustrating the great superiority of a "gravity

road" over all others for the cheap transportation of anthracite

over the ridges surrounding the coal-fields of Pennsylvania.

The true system, exemplified twenty years ago by its present

superintendent, John B. Smith, Esq., of uniting the interests

of the laboring-man with those of the company, as far as possible,

has been one of the most efficient measures whereby "strikes"

have been obviated, and the general prosperity of the road steadily

advanced.

Through the instrumentality of Mr. Smith this has been done

in a manner so uniform yet unobtrusive, as to make it a model

coal-road. It carries no passengers.

This company, having a capital of about $4,000,000, gives employment

to over three thousand men.

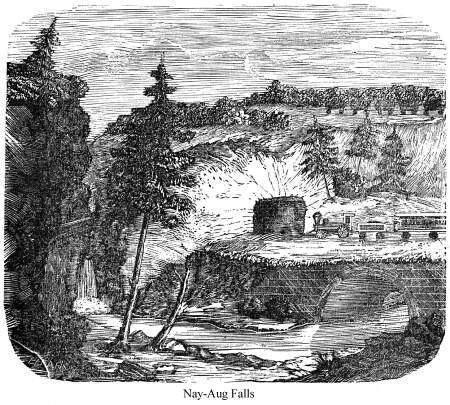

FROM PITTSTON TO HAWLEY.

A ride upon a coal-train over the gravity road of the Pennsylvania

Coal Company, from Pittston to Hawley, is not without interest

or incident. Starting from the banks of the Susquehanna, it gradually

ascends the border of the Moosic Mountain for a dozen miles, when,

as if refreshed by its slow passage up the rocky way, it hurries

the long train down to the Dyberry at Hawley with but a single

stoppage.

Let the tourist willing to blend venture with pleasure, step

upon the front of the car as it ascends Plane No. 2, at Pittston,

and brings to view the landscape of Wyoming Valley, with all its

variety of plain, river, and mountain, made classic by song and

historic by her fields of blood. The Susquehanna, issuing from

the highland lakes of Otsego, flows along, equaled only in beauty

by the Rhine, through a region famed for its Indian history—the

massacre upon its fertile plain, and the sanguinary conflict between

the Yankees and Pennymites a century ago. The cars, freighted

with coal, move their spider-feet toward Hawley. Slow at first,

they wind around curve and hill, gathering speed and strength

as they oscillate over ravine, woodland, and water. Emerging from

deep cuts or dense woods, the long train approaches Spring Brook.

Crossing this trout stream upon a trestling thrown across the

ravine of a quarter of a mile, the cars slacken their speed as

they enter the narrow rock-cut at the foot of the next plane.

While looking upon the chiseled precipice to find some egress

to this apparent cavern, the buzz of the pulley comes from the

plane, and through the granite passage, deep and jaw-like, you

are drawn to a height where the glance of the surrounding woods

is interrupted by the sudden manner in which you are drawn into

the very top of engine-house No. 4.

The Lybian desert, in the desolation of its sands, offers more

to admire than the scenery along the level from No. 4 to No. 5.

Groups of rock, solitary in dignity and gray with antiquity, are

seen upon every side; trees grow dwarfed from their accidental

foothold; and only here and there a tuft of wild grass holds its

unfriendly place. The babbling of a brook at the foot of No. 5,

alone falls pleasantly upon the ear. As the cars roll up the plane,

the central portion of the valley is brought before the eye on

a scale of refreshing magnificence. The features of the scenery

become broader and more picturesque. The Moosic range, marking

either side of the valley, so robed with forest to its very summit

as to present two vast waves of silent tree-top, encircle the

ancient home and stronghold of Capoose. As you look down into

this amphitheater, crowded with commercial and village life, catching

a glimpse of the river giving a richer shade to a meadow where

the war-song echoed less than a century ago, evidences of thrift

everywhere greet and gladden the eye.

At No. 6, upon the northern bank of the Roaring Brook, are

located the most eastern mines of this company, being those which

are situated the nearest to New York City. These consist of a

series of coal deposits, varied in purity, thickness, and value,

but all profitably worked. The largest vein of coal mined here

is full eight feet thick, and is the highest coal mined on the

hill northwest of plane No. 6.

Upon the opposite range of the Moosic Mountain, in the vicinity

of Leggett's Gap, this same stratum of coal is worked by other

companies. Each acre of coal thus mined from this single vein

yields about 10,000 tons of good merchantable coal.

The Delaware, Lackawanna, and Western Railroad, crosses that

of the Pennsylvania at No. 6, giving some interest to the most

flinty rocks and soil in the world. No. 6 is a colony by itself.

It is one of those humanized points destitute of every natural

feature to render it attractive.

On either side of the ravine opening for the passage of Roaring

Brook, the sloping hill, bound by rock, is covered with shanties

sending forth a brogue not to be mistaken; a few respectable houses

stand in the background; the offices, store-house, workshops,

and the large stone car and machine shops of the company are located

on the northern bank of the brook. Some sixty years ago a sawmill

erected in this piny declivity by Stephen Tripp, who afterward

added a small grist-mill by its side, was the only mark upon the

spot until the explorations and survey of this company. This jungle,

darkened by laurels blending their evergreen with the taller undergrowth,

was more formidable from the fact that during the earlier settlement

of Dunmore it was the constant retreat of wolves.

Over this savage nook, industry and capital have achieved their

triumphs and brought into use a spot nature cast in a careless

mood. At the head of No. 6 stand the great coal screens for preparing

the finer quality of coal, operated by steam-power.

Up the slope of the Moosic, plane after plane, you ascend along

the obliterated Indian path and Connecticut road, enjoying so

wide a prospect of almost the entire valley from Pittston to Carbondale,

that for a moment you forget that in the crowded streets elsewhere

are seen so many bodies wanting souls. Dunmore, Scranton, Hyde

Park, Providence, Olyphant, Peckville, Green Ridge, and Dickson

appear in the foreground, while the Moosic, here and there serrated

for a brook, swings out its great arms in democratic welcome to

the genius of the artificer, first shearing the forest, then prospering

and perfecting the industrial interest everywhere animating the

valley. The long lines of pasturage spotted with the herd, the

elongated, red-necked chimneys distinguishing the coal works multiplied

almost without number in their varied plots, give to these domains

a picturesqueness and width seen nowhere to such an advantage

in a clear day as on the summit of Cobb Mountain, two thousand

feet above the tide.

Diving through the tunnel, the train emerges upon the "barrens,"

where, in spite of every disadvantage of cold, high soil, are

seen a few farms of singular productiveness. The intervening country

from the tunnel to Hawley, partakes of the hilly aspect of northern

Pennsylvania, diversified by cross-roads, clearings, farm-houses,

and streams. Here and there a loose-tongued rivulet blends its

airs with the revolving car-wheel humming along some shady glen,

and farther along, the narrow cut, like the sea of old, opens

for a friendly passage. Down an easy grade, amidst tall, old beechen

forests half hewn away for clearings and homes of the frugal farmers,

the cars roll at a speed of twelve miles an hour over a distance

of some thirty miles from the tunnel, when, turning sharply around

the base of a steep hill on the left, the cars land into the village

of Hawley, a vigorous settlement, existing and sustaining itself

principally by the industrial manipulations of this company.

A little distance below the village, the Wallenpaupack, after

leaping 150 feet over the terraced precipice, unites with the

Lackawaxen, a swift, navigable stream in a freshet, down whose

waters coal was originally taken from the Lackawanna Valley to

the Delaware in arks.

It is fourteen miles to Lackawaxen upon the Delaware, where,

in 1779, a bloody engagement took place between John Brant, the

famous chief of the Six Nations, and some four hundred Orange

county militia.

The Tories and Indians had burned the town of Minisink, ten

miles west of Goshen, scalping and torturing those who could not

escape from the tomahawk by flight. Being themselves pursued by

some raw militia, hastily gathered from the neighborhood for the

purpose, they retreated to the mouth of the Lackawaxen. Here Brant

with his followers formed an ambuscade. The whites, burning to

avenge the invaders of their firesides, incautiously rushed on

after the fleeing savages, ignorant or forgetting the wily character

of their foe. As the troops were rising over a hill covered with

trees, and had become completely surrounded in the fatal ring,

hundreds of savages poured in upon them such a merciless fire,

accompanied with the fearful war-whoop, that they were at once

thrown into terrible confusion. Every savage was stationed behind

the trunk of some tree or rock which shielded him from the bullets

of the militia. For half an hour the unequal conflict raged with

increasing fury, the blaze of the guns flashing through the gloom

of the day, as feebler and faster fell the little band. At length,

when half of their number were either slain or so shattered by

the bullets as to be mere marks for the sharp-shooters, the remainder

threw away their guns and fled; but so closely were they in turn

pursued by the exultant enemy that only thirty out of the entire

body escaped to tell the sad story of defeat. Many of these reached

their homes with fractured bones and fatal wounds. The remains

of those who had fallen at this time were gathered in 1822, and

deposited in a suitable place and manner by the citizens of Goshen.

The New York and Erie Railroad have sent up a branch road from

a point near this battle-ground to Hawley, thus giving to the

Pennsylvania Coal Company an unfrozen avenue to the sea-board,

besides dispensing in a great degree with water facilities offered

and enjoyed until the completion of this branch in 1863.

From 1850 to 1866, 9,308,396 tons of coal was brought from

the mines to Hawley, being an average of 581,775 tons per year.

Report of Coal transported over the Pennsylvania

Coal Company's Railroad for week and for year ending December

31, 1868, and for corresponding period last year:—

|

By Rail, week ending December 31 |

12,786.03 |

|

|

By Rail Previously |

912,063.70 |

|

|

TOTAL |

|

924,849.13 |

|

|

|

|

|

By Canal, week ending December 26 |

Closed. |

|

|

By Canal Previously |

29,004.19 |

|

|

TOTAL |

|

29,004.19 |

|

|

|

|

|

Total by Canal and Rail, 1868 |

|

953,854.12 |

|

Total To same date, 1867 |

|

861,729.15 |

|

INCREASE |

|

92,124.17 |

JNO. B. SMITH, Superintendent.

While a great part of the coal carried to Hawley acknowledges

the jurisdiction of this branch road, a limited portion is unloaded

into boats upon the Delaware and Hudson Canal.

Once emptied, the cars return to the valley upon a track called

the light track, where the light or empty cars are self-gravitated

dowel a heavier grade to the coal-mines. Seated in the "Pioneer,"

a rude passenger concern, losing some of the repelling character

of the coal car, in its plain, pine seats and arched roof, you

rise up the plane from the Lackawaxen Creek a considerable distance

before entering a series of ridges of scrub-oak land, barren both

of interest and value until made otherwise by the fortunes of

this company. Leaving Palmyra township, this natural barrenness

disappears in a great measure as you enter the richer uplands

of Salem, where an occasional farm is observed of great fertility,

in spite of the accompanying houses, barns, and fences defying

every attribute of Heaven's first law. About one mile from the

road, amidst the quiet hills of Wayne County, nestles the village

of Hollisterville. It lies on a branch of the Wallenpaupack, seven

miles from Cobb Pond, on  the

mountain, and ten miles above the ancient "Lackawa"

settlement. AMASA HOLLISTER, with his sons, Alpheus, Alanson,

and Wesley, emigrated from Hartford, Connecticut, to this place

in 1814, when the hunter and the trapper only were familiar with

the forest. Many of the social comforts of the village, and much

of the rigid morality of New England character can be traced to

these pioneers. Up No. 21 you rise, and then roll toward the valley.

The deepest and greatest gap eastward from the Lackawanna is Cobb's,

through which flows the Roaring Brook. This shallow brook, from

some cause, appears to have lost much of its ancient size, as

it breaks through the picturesque gorge with shrunken volume to

find its way into the Lackawanna at Scranton. the

mountain, and ten miles above the ancient "Lackawa"

settlement. AMASA HOLLISTER, with his sons, Alpheus, Alanson,

and Wesley, emigrated from Hartford, Connecticut, to this place

in 1814, when the hunter and the trapper only were familiar with

the forest. Many of the social comforts of the village, and much

of the rigid morality of New England character can be traced to

these pioneers. Up No. 21 you rise, and then roll toward the valley.

The deepest and greatest gap eastward from the Lackawanna is Cobb's,

through which flows the Roaring Brook. This shallow brook, from

some cause, appears to have lost much of its ancient size, as

it breaks through the picturesque gorge with shrunken volume to

find its way into the Lackawanna at Scranton.

This gap in the mountain, deriving its name from Asa Cobb,

who settled in the vicinity in 1784, lies three miles east of

Scranton. It really offers to geologist or the casual inquirer

much to interest. This mountain rent, unable longer to defy the

triumphs of science, seems to have been furrowed out by the same

agency which drew across the Alleghany the transverse lines diversifying

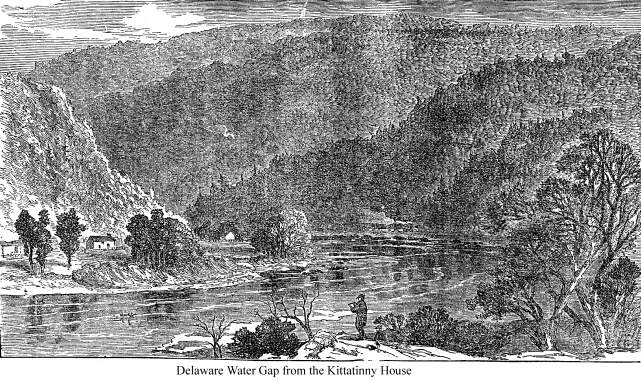

the entire range. Like the mountain at the Delaware Water Gap,

it bears evidence of having once been the margin of one of the

lakes submerging the country at a period anterior to written or

traditional history. Emerging from beech and maple woodlands,

you catch a glimpse of a long, colossal ledge, bending in graceful

semicircle, rising vertically from the Roaring Brook some three

hundred feet or more. Its face, majestic in its wildness, as it

first greets the eye, reminds one of the palisades along the Hudson.

As it is approached upon the cars, the flank of the mountain defies

further progress in that direction, when the road, with a corresponding

bend to the left, winds the train from apparent danger, moving

down the granite bank of the brook deeper and deeper into the

gorge, enhanced in interest by woods and waterfall. The hemlock

assumes the mastery of the forest along the brook, whose waters

whiten as they pour over precipice after precipice into pools

below, which but few years since were so alive with trout, that

fishing half-an-hour with a single pole and line supplied the

wants of a family for a day with this delicious fish. In the narrowest

part of the gap, the cars run on a mere shelf, cut from the rock

a hundred feet from the bed of the stream, while the mountain,

wrapped in evergreens, rises abruptly from the track many hundred

feet.

Greenville, a fossilized station on the Delaware, Lackawanna,

and Western Railroad, and once the terminus of the Lackawanna

Railroad, lies on a slope opposite this point.

The great pyloric orifice of Cobb's Gap, once offering

uncertain passage to the Indian's craft, illustrates the achievement

of art over great natural obstacles. Roaring Brook, Drinker's

turnpike, now used as a township road, the Pennsylvania and the

Delaware, Lackawanna, and Western Railroad, find ample place under

the shadow of its walls.

A ride of an hour, far up from the bottom of the valley through

a forest trimmed of its choicest timber by the lumbermen and shingle-makers,

brings the traveler again to Pittston, renovated in spirits and

vigor, and instructed in the manner of diffusing anthracite coal

throughout the country.

DELAWARE, LACKAWANNA, AND WESTERN RAILROAD.

Historical Summary of the Susquehanna and Delaware Canal

and Railroad Company (Drinker's Railroad)—The Leggett's Gap

Railroad—The Delaware and Cobb's Gap Railroad Company—All

merged into the Delaware, Lackawanna, and Western Railroad.

Imperfect as was the knowledge of the value of coal forty years

ago, large bodies of it being discovered here and there in the

valley, mostly upon or near the surface, led the late Henry W.

Drinker to comprehend and agitate a plan of connecting the Susquehanna

River at Pittston with the Delaware at the Water Gap, by means

of a railroad running up the Lackawanna to the mouth of Roaring

Brook, thence up that stream to the placid waters of Lake Henry,

crossing the headsprings of the Lehigh upon the marshy table-land

forming the dividing ridge between the Susquehanna and Delaware,

and down the Pocono and the rapid Alanomink to the Water Gap,

with a view of reaching a market.

This was in 1819. The contemplated route, marked by the hatchet

over mountain and ravine profound in the depth of their solitude,

had no instrumental survey until eleven years afterward, but an

examination of the country, with which no woodman was more familiar

than Drinker, satisfied him that the intersecting line of communication

was not only feasible, but that its practical interpretation would

utilize the intervening section, and give action and impulse to

many an idle ax. In April, 1826, he easily obtained an act of

incorporation of the "Susquehanna and Delaware Canal and

Railroad Company." The charter implied either a railroad

operated up the planes by water, or a canal a portion of the way.

The "head-waters of the river Lehigh and its tributary stream,"

were prohibited from being used for feeding the canal, as it might

"injure the navigation of said river, from Mauch Chunk to

Easton." By reference to the original report and survey of

this road, it appears that horses were contemplated as the motive

power between the planes, that toll-houses were to be established

along the line, and collectors appointed, and that the drivers

or conductors of "such wagon, carriage, or conveyance, boat

or raft, were to give the collectors notice of their approach

to said toll-houses by blowing a trumpet or horn."

Henry W. Drinker, William Henry, David Scott, Jacob D. and

Daniel Stroud, Jai-ties N. Porter, A. E. Brown, S. Stokes, and

John Coolbaugh, were the commissioners.

Among the few persons in Pennsylvania willing to welcome and

recognize the practicability of a railroad route in spite of the

wide-spread distrust menacing it in 1830, stood prominently a

gentleman, by the aid of whom, the Indian Capoose region of Slocum

Hollow changed the ruggedness of its aspect—William Henry.

In fact, Messrs. Henry and Drinker were two of the most indefatigable

and energetic members of the board.

In 1830, a subscription of a few hundred dollars was obtained

from the commissioners; in May, 1831, Mr. Henry, in accordance

with the wishes of the board, engaged Major Ephraim Beach, C.

E., to run a preliminary line of survey over the intervening country.

By reference to the old report of Major Beach, it will be seen

that the present line of the southern division of the Delaware,

Lackawanna, and Western Railroad is, in the main, much the same

as that run by him at this time. Seventy miles in length the road

was to be made, at a total estimated cost of $624,720. Three hundred

and thirty-six wagons (cars), capable of carrying over the road

240, 000 tons of coal per year, were to be employed.

Coal at this time was worth $9 per ton in New York, while coal

lands in the valley could be bought at prices varying from $10

to $20 per acre.

It was not supposed by the commissioners that the coal trade

alone could make this road one so profitable, but it was originally

their object to connect the two at these points, so as to participate

in the trade upon the Susquehanna. For the return business

it was thought that "iron in bars, pig, and castings, would

be sent from the borders of the Delaware in Pennsylvania and New

Jersey, and that limestone in great quantities would be transported

from the same district and burned in the coal region, where fuel

would be abundant and cheap." [Commissioners'

Report of the Route, 1832].

Simultaneously with this survey was the route of the Lackawannock

and Susquehanna, or Meredith Railroad, leading from the mouth

of Leggett's Creek in Providence up to that graceful loop in the

Susquehanna, called Great Bend, forty-seven and a half miles away,

undertaken and surveyed by the late James Seymour, four years

after the granting of its charter.

Near the small village of Providence these two roads, neither

of which contemplated the use of locomotives in their reliance

upon gravity and seven inclined planes, were to form a junction,

and expected to breathe life and unity into the iron pathway that

was to grope its way out of a valley having scarcely a name away

from its immediate border. Neither. road proposed to carry passengers.

The report of the commissioners, presenting the subject in

its most attractive light, failed to excite the attention it deserved.

Men reputed as reliable looked upon the scheme as unworthy of

serious notice. Those who had achieved an indifferent livelihood

by the shot-gun or the plow, saw no propriety in favoring a plan

whose fulfillment promised no protection to game or greater product

to the field.

The few who felt that its success would interweave its advantages

into every condition of life, were not dismayed.

In the spring of 1832, a sufficient amount of stock having

been subscribed, the company was organized: Drinker elected president,

John Jordon, Jr., secretary, and Henry, treasurer. At a subsequent

meeting of the stockholders, the president and treasurer were

constituted a financial committee to raise means to make the road,

by selling stock, issuing bonds, or by hypothecating the road,

&c. The engineer's map, the commissioners' report, and newspaper

articles were widely diffused, to announce the material benefits

to result by the completion and acquisition of this new thoroughfare.

The Lackawanna Valley, set in its green wild ridges, known

in New York City only by the Delaware and Hudson Canal Company,

then in the fourth year of its existence, confounded often with

the Lackawaxen region lying upon the other side of the

Moosic Mountain, neither Drinker's nor Meredith's charter was

received with favor or attention.

The advantages of railroads were neither understood nor encouraged

by the inhabitants of the valley in 1832, because the slow ox-team

or jaded saddle-horse thus far had kept pace with its development.

To render the scheme, however, more comprehensive and general

in its character, and make more certain the building of the Drinker

railroad, a continuous route was explored for a gravity railroad,

"from a point in Cobb's Gap, where an intersection or connection

can be conveniently formed with the Susquehanna and Delaware Railroad,

in Luzerne County," up through Leggett's Gap, and running

in a northwesterly direction to the State of New York.

This was the Leggett's Gap Railroad, an inclined plane road

which, when completed, was expected to receive the trade along

the fertile plains of the Susquehanna, Chenango, and the Chemung,

now enjoyed so profitably by the New York and Erie Railroad.

H. W. Drinker, Elisha S. Potter, Thomas Smith, Dr. Andrew Bedford,

and Nathaniel Cottrill—the last two of whom are now living-were

among the original commissioners.

Public meetings were now called by the friends of the Drinker

road, at the Old Exchange in Wall Street, New York, to obtain

subscriptions to the stock of the company, and, while many persons

acknowledged the enterprise to be a matter of more than common

interest to the country generally, as it promised when completed,

to furnish a supply of coal from the hills of Luzerne County,

a county where thousands of millions of tons of the best anthracite

coal could be mined from a region of more than thirty-three miles

in length, and averaging more than two miles in width, underlaid

with coal probably averaging fifty feet in thickness, and besides

this, unlike most other mining portions of the world, it abounded

in agricultural fertility.

While these facts where generally conceded, they produced no

other, effect, than bringing from capitalists the favorable opinion

that final triumph probably awaited their hopes. In Morristown,

Newton, Belvidere, Newark, and other places in New Jersey; at

Easton, Stroudsburg, Dunmore, Providence, and Kingston, in Pennsylvania,

meetings were called to draw the attention of the public mind

and acquire the requisite means to open this highway through the

wilderness, where the wolf, crouched in the swamp; bestowed with

his gray eye as friendly a glance upon the project as many capitalists

were inclined to give it. Every sanguine hope, every flattering

promise made in a spirit of apparent earnestness languished and

died like the leaves of autumn.

At length, engagements were made with New York capitalists

to carry the matter forward to a favorable termination, provided

that Drinker and his friends would obtain a charter for a continuous

line of gravity railroad up the Susquehanna, from Pittston to

the New York State line. In 1833, a perpetual charter for such

a road was obtained by their agency, and the first installment

of five dollars was paid, according to the act of Assembly. In

itself it was considered, that in connection with other roads,

at or near the Delaware Water Gap to New York City, it would be

with its terminus at Jersey City eastwardly, and the State line

near Athens, in Pennsylvania, westward, the shortest and the best

line the natural avenues indicated from New York west. It was

shown by the official report of a survey made in 1827, by John

Bennett, of Kingston, Pennsylvania, that the distance from the

mouth of the Lackawanna of eighty-six miles had but two hundred

and fourteen feet fall, or about two and a half feet per mile,

the acclivity for the whole distance being in general nearly equal,

and beyond this to the city of Elmira at about the same grade.

The vast project of the New York and Erie Railroad was agitating

southern New York at this time. Of the seven commissioners, John

B. Jervis, Horatio Allen, Jared Wilson, and William Dewy urged

the adoption of the present route, while F. Whittlesey, Orville

W. Childs, and Job Pierson reported adversely to it.

The New York gentlemen interested in Drinker's route, having

full faith in the realization of an idea promising control of

a line reaching the same point on the New York and Erie Railroad

(as laid down by Judge Wright, civil engineer, but on which nothing

more had yet been done), at a distance of eighty-one miles short

of this line, while running through both the anthracite and bituminous

coal districts upon easier grades, were greatly encouraged to

hope for success; several sections in the "Susquehanna Railroad"

law were, by supplements, so amended by legislative enactments

as to fulfill upon that point every expectation.

In October, 1835, the services of Doctor George Green, of Belvidere,

who was a friend of this improvement, and who originated the "Belvidere

Delaware Railroad," were procured. William Henry's note,

indorsed by Henry W. Drinker, accepted and indorsed by the cashier

of the Elizabeth Bank as "good," was taken by the doctor

to the Wyoming Bank at Wilkes Barre as a deposit and payment,

in compliance with the law called the "Susquehanna Railroad"

act. of Assembly of 1833.

In consequence of the commercial embarrassments alienating

credit and confidence throughout the entire country in 1835-6,

the New York party, impoverished and appalled by the shock, could

give no further thought to the road. Other parties being prostrated

by insolvency or death, the positive spirit, inaugurating the

company, carried with it thus far a success decidedly negative

and skeptical.

Ten years had thus escaped, and not a single tie nor rail had

shod the road; here and there a few limbs clipped from the forest-tree

to aid the surveyor, and a few rods graded for the flat iron bar,

bore evidence of the hope of the directors.

In the summer of 1836, there was traveling in the United States

an English nobleman named Sir Charles Augustus Murray, who, learning

of the important character of this proposed road from one of his

friends, became interested in its success. A correspondence ensued,

which led to a meeting of the friends of the project, at Easton,

June 18, 1836; Mr. Drinker and Mr. Henry on the part of the railroad

company, and Mr. Armstrong of New York, Mr. C. A. Murray, and

Wm. F. Clemson of New Jersey, wrote out articles of association;

the railroad committee fully authorized Mr. Murray to raise, as

he proposed to do, 100,000 pounds sterling in England, conditional

that the company should raise the means to make a beginning of

the work. Mr. Henry accompanied him to New York, and furnished

him with the power of attorney, under seal expressly made for

the purpose, and on the eighth of August, 1836, Mr. Murray sailed

for Europe. Mr. Henry at once met and made arrangements with the

Morris Canal Board of Directors to raise $150,000 on stock subscriptions

to commence the road, but before these arrangements had matured,

discouraging news came from England through Mr. Murray, who informed

the company that the prostrated monetary affairs of Europe rendered

any assistance by him out of the question.

To this meeting, which lasted three days, in the village of

Easton, can be traced the starting of the iron-works in Slocum

Hollow, whose varied and wide-spread prosperity have animated

the entire domain of the Lackawanna. [See History

of Scranton].

The first iron-works in Scranton after those of Slocums', were

erected in 1840. In the summer of 1842, after the artificers gathered

around the Scranton furnaces had learned to smelt iron with the

lustrous anthracite, the directors of the railroad held only annual

meetings. Drinker and Henry had each expended nearly their entire

resources to fructify a project whose magnitude found no place

or conception in the public mind; this being done in vain, postponed

further sacrifices and efforts to stretch the iron fiber from

river to river, until greater wants from the sea-board came up

to the coal heaps, and established mutual confidence instead of

general distrust.

The simple acquisition of Slocum Hollow, in 1840, by a New

Jersey company, had but little interest outside of parties concerned

in the purchase. Who were taxed for the rough pasture-land cleared

on Roaring Brook, none cared to inquire. Its purchase, however,

originally suggested by Mr. Henry with especial reference to the

furtherance of Drinker's road, favored that result sooner than

was anticipated. With the concentration and expansion of capital

here at this time, a business was generated which called for a

better communication with the seaboard than the ox-team or the

sluggish waters of a canal frozen up at least six months of every

year.

Col. Scranton, in the simplicity of whose character the whole

country acquiesced and felt proud, representing the interests

of the iron-makers in Scranton, yet willing to give power to a

measure full of public good, conceived the project, in 1847, of

opening communication from the ironworks northward to the lakes

by a locomotive instead of a gravity road run by plane, stationary

engine, and level, as Drinker's, Meredith's, and the Leggett charters

all contemplated. The charter of the last-named road, kept alive

by the influence of Dr. Andrew Bedford, Thomas Smith, Nathaniel

Cottrill, and other spirited gentlemen, was purchased by the "Scranton

Company" in 1849, by the suggestion of Colonel Scranton.

A survey was made the same year; the road was commenced in 1850.

For the purpose of giving favor and strength to a project unable

to make its way to a practical solution without capital from abroad,

a road was chartered in April, 1849, to run from the Delaware

Water Gap to some point on the Lackawanna near Cobb's Gap, called

"The Delaware and Cobb's Gap Railroad Company." The

commissioners, Moses W. Coolbaugh, S. W. Schoomaker, Thos. Grattan,

H. M. Lebar, A. Overfield, I. Place, Benj. Y. Rush, Alpheus Hollister,

Samuel Taylor, F. Starburd, Jas. H. Stroud, R. Bingham, and W.

Nyce, held their first meeting at Stroudsburg, December 26, 1850,

choosing Col. Geo. W. Scranton president.

The northern division of "The Lackawanna and Western Railroad

Company," carried by genius and engineering skill for sixty

miles over the rough uplands distinguishing the country it traverses

from Scranton to Great Bend, was opened for business in October,

1851, thus enabling the inhabitants of the valley to reach New

York by a single day's ride instead of two, as before.

Travel and traffic, hitherto finding

its way from the basins of Wyoming and the Lackawanna to Middletown

or Narrowsburg by stage, and thence along the unfinished Erie,

now diverged westward, via Great Bend, sixty miles away,

before apparently beginning a journey eastward to New York. This

unphilosophical and wasteful manner of groping among the hills

in the wrong direction before starting for New York, directed

the intelligence of the mass toward the purpose of Col. Scranton,

of planing a continuous roadway direct to New York, via

the celebrated Delaware Water Gap. Travel and traffic, hitherto finding

its way from the basins of Wyoming and the Lackawanna to Middletown

or Narrowsburg by stage, and thence along the unfinished Erie,

now diverged westward, via Great Bend, sixty miles away,

before apparently beginning a journey eastward to New York. This

unphilosophical and wasteful manner of groping among the hills

in the wrong direction before starting for New York, directed

the intelligence of the mass toward the purpose of Col. Scranton,

of planing a continuous roadway direct to New York, via

the celebrated Delaware Water Gap.

The original charter of Drinker's railroad was purchased of

him in 1853, by the railroad company, for $1,000. Immediately

after this, a joint application was made by the "Delaware

and Cobb's Gap Railroad Company," and the "Lackawanna

and Western Railroad Company," for an act of the Legislature

for their consolidation, which was granted March 11, 1853, and

the union consummated under the present, name of "The Delaware,

Lackawanna, and Western Railroad Company."

Of this consolidated road, the late George W. Scranton was

unanimously elected President: how well he filled this position

until compelled to exchange it for the invalid's shelf, let the

movement of the iron pathway across a valley which would be comparatively

idle to-day without it—let the mutually satisfactory adjustment

of every conflicting interest arising in the progress of this

great road—let the spirit of his administration, characterized

by qualities both sterling and comprehensive—more than this,

let the simple fact that he, inspiring capitalists with the same

confidence he himself had acquired and cherished, was able to

draw forth the wherewithal to complete a road deriving its origin

and vigor from him, bear ample and praiseworthy testimony.

The vast business of this road, which in the year of 1868 carried

1,728,785.07 tons of anthracite, requires one hundred locomotives,

about five thousand coal-cars, and gives employment to over 5,000

men. Its total disbursements at Scranton alone, through H. A.

Phelps, the courteous paymaster of the road, amounted, during

the last year, to over $4,000,000, while a considerable sum diffused

itself through the treasury department in New York.

The same efficiency and ability

with which Hon. John Brisbin acquired popularity as the president

of the great primitive locomotive railroad in the Lackawanna Valley,

from 1856 to 1867, has been continued and even augmented by Samuel

Sloan, Esq., its present vigilant president, and formerly the

presiding officer of the Hudson River Railroad, whose admirable

management of the interests of the Delaware, Lackawanna, and Western

Railroad, has placed it upon a basis reliable and remunerative,

and given it a character, even beyond the States it traverses,

enjoyed by few, if any, railroads in the country. The same efficiency and ability

with which Hon. John Brisbin acquired popularity as the president

of the great primitive locomotive railroad in the Lackawanna Valley,

from 1856 to 1867, has been continued and even augmented by Samuel

Sloan, Esq., its present vigilant president, and formerly the

presiding officer of the Hudson River Railroad, whose admirable

management of the interests of the Delaware, Lackawanna, and Western

Railroad, has placed it upon a basis reliable and remunerative,

and given it a character, even beyond the States it traverses,

enjoyed by few, if any, railroads in the country.

The lease of the Morris and Essex road by the Delaware, Lackawanna,

and Western, for an almost indefinite term of years, establishes

more intimate relations between the Lackawanna Valley and the

sea-board than ever enjoyed before, and marks an era in the history

of coal transportation, second, only in importance to the conception

of the original gravity railroad stretched like a rainbow over

the Moosic in 1826-8 by Warts brothers. Hitherto, the former road,

vigorous with local traffic, strove only to compete with a diverse

railway for doubtful dividends, without a wish to advance or retard

the welfare of the valley. By a stroke of policy seldom surpassed

in the grandeur of its results, all this was changed in January,

1869, by the practical foresight of President Sloan and his associates.

The consolidation of these two roads gives a future interest to

the Delaware, Lackawanna, and Western road far beyond the appreciation

of the hour. It abbreviates distance, offers a continuous and

controllable rail from the mines to New York, increases the value

and tonnage of the road almost fourfold, while the travel over

it for all time to come will make one steady, living stream of

various lineage and faith, steady, remunerating, and thus commemorate

the wisdom of the men who inaugurated the movement. The superintendency

of the Morris and Essex division of the line has fallen into the

experienced hands of Hon. John Brisbin.

THE LACKAWANNA AND BLOOMSBURG RAILROAD.

After the locomotive railroad from the Lackawanna Valley had

become a fixed fact by the genial efforts of those to whom its

failure or its success had been intrusted, other roads began to

spring into a charter being. Among such was the Lackawanna and

Bloomsburg Railroad. An act incorporating this company was passed

in April, 1852, but not until some valuable and essential amendments

were obtained for the charter the next year, by the able efforts

of one of the members of the Pennsylvania Legislature—Hon.

A. B. Dunning—did it possess any available vitality. This

road, running from Scranton to Northumberland, is eighty miles

in length, passing through the historic valley of Wyoming, where

the poet Campbell drew, in his Gertrude, such pictures of the

beautiful and wild. It also passes along the Susquehanna, over

a portion of the old battle-ground, where, in 1778, a small band

of settlers marched forth from Forty Fort, in the afternoon, to

fight the spoilers of their firesides, and where, after the battle,

the long strings of scalps dripping from the Indian belts, and

the hatchets reddened with the slain, told how sore had been the

rout, and how terrible the massacre; that followed. The dweller

in wigwams has bid a long farewell to a region so full of song

and legend, and where can be found the one to-day who, as he looks

over the old plantation of the Indian Nations, once holding their

great council fires here, upon the edge of the delightful river,

surrounded by forest and inclosing mountain, can wonder that they

fought as fights the wild man with warclub and tomahawk, to regain

the ancient plains of their fathers?

Wyoming Valley, taken as a whole, compensates in the highest

degree for the trouble of visiting it. The grand beauty of the

old Susquehanna and the sparkling current of its blue waters nowhere

along its entire distance appears to better advantage than does

it here. Along the Po or the Rhine, there loom up the gray walls

of some castle dismantled and stained with the blood of feudal

conflict; here on the broad acres of Wyoming turned into culture,

humanity wears a smile nowhere more sweet or lovely.

The tourist who wishes to visit this truly interesting valley,

can step into the cars of the Lehigh and Susquehanna, or the Lackawanna

and Bloomsburg Railroad Company, at Scranton, and in twenty minutes

look "On Susquehanna's side, fair Wyoming!" Across the

river, half a mile from Campbell's Ledge, near the head of the

valley, is seen the battle-ground. About three miles below Pittston,

left of the village of Wyoming, rises from the plain a naked monument—an

obelisk of gray masonry sixty-two and a half feet high, which

commemorates the disastrous afternoon of the third of July, 1778.

Near this point reposes the bloody rock around which, on

the evening of that ill-fated day, was formed the fatal ring of

savages, where the Indian queen of the Senecas, with death-mall

and battle-ax, dashed out the brains of the unresisting captives.

The debris of Forty Fort, the first fort built on the north

side of the Susquehanna by the Connecticut emigrants, in 1769,

is found a short distance down the river from this rock.

The Lackawanna and Bloomsburg Railroad, while it is a valuable

auxiliary to the Delaware, Lackawanna, and Western Railroad, in

whose interests it is operated, enjoyed all the advantages of

travel between central Pennsylvania and the Lackawanna Valley

until the Lehigh and Susquehanna and the Lehigh Valley railroads,

bounding over the mountain with the celerity and speed of a deer,

alienated a portion of the trade and travel.

Having the advantage of collieries with an aggregate yearly

capacity of a million tons of coal, threading its way along the

green belt of the Susquehanna over rich beds of iron ore, worked

in Danville by ingenious artificers who have adopted science as

their patron, it will ever stand prominent among the railroads

of the country.

While the Delaware, Lackawanna, and Western Railroad, with

its greater length of thirty-three miles, carried 187,583 passengers

during the year 1867, the Lackawanna and Bloomsburg transported

269,564—an excess of 81, 981 persons.

No railroad in the country of its length, lined with scenery

always exhilarating, would better repay the visit of a few days

in summer or autumn, than will this. It is, in fact, all picturesque,

while portions of it are really magnificent. Thundering along

the border of the river and the canal, at a rate of thirty miles

an hour, a glimpse is now caught and then lost, of old gray mountain

crags and glens, covered with forest just as it grew—of sleepy

islands, dreaming in the half-pausing stream—of long, narrow

meadows, stretched along with sights of verdure and sounds of

life, and now and then a light cascade, tuned by the late rains,

comes leaping down rock after rock, like a ribbon floating in

the air! How the waters whiten as they come through the tree-tops

with silver shout from precipice to precipice in the bosom of

some rock, cool and fair-lipped! The scenery is especially grand

at Nanticoke—the once wild camp-place of the Nanticokes—where

Wyoming Valley terminates, and where the noble river, wrapped

up in the majesty of mountains, glides along as languidly as when

the red man in his narrow craft shot over the ripple.

Mr. James Archibald, life-long in his earnest devotion to the

interests of the Lackawanna Valley, is president of the road.

SKETCH OF THE EARLY HISTORY OF THE LEHIGH AND SUSQUEHANNA

RAILROAD.

This road, running from Providence to Easton, a distance of

120 miles, threads a section of country surpassed by no other

in the State for the grandeur of its scenery or the interest of

its history.

When the Indian civilizers first began to fraternize with the

sachems of the Lehigh at Fort Allen or Gnadenhutten (now Weissport)

in 1746, all knowledge of anthracite coal was so limited, that

the word "coal" was noted upon but a single map within

the Province of Pennsylvania. The casual discovery of coal, half

a century later, near this settlement, gave fetal life to the

Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company, and a prominence to the history

of this region not otherwise enjoyed.

At the confluence of the Ma-ha-noy (the loud, laughing stream

of the Indian) with the Lehigh, this fort was located, eighteen

miles above Bethlehem, forty miles by the warriors' trail from

Teedyuscung's plantation at Wyoming. It was the first attempt

of the whites to carry civilization into the provincial acquisitions

of Penn above the Blue Mountain. Why a region so rough in its

general exterior should have been chosen for a sheltering place,

can be accounted for upon no other theory than that the gray rock

here bordering the Lehigh, took the place in memory of the Elbe

in their fatherland emerging from the crags of the Alps.

This place, often visited by sachem and chief, whom the missionaries

first conciliated, then endeavored to Christianize, "numbered

500 souls in 1752." [Miner's Wyoming,

p. 41] Braddock's defeat, two years later, opened the forest

for the uplifted tomahawk. Some of the Six Nations, exchanging

wampum and whiffs of the calumet with their Moravian brothers,

danced the war-dance before Vaudreuil, Governor of New France

(New York State). " We will try the hatchet of our fathers

on the English," said the chiefs at Niagara, "and see

if it cuts well." [Vaudreuil to the Minister,

July 13, 1757.]

The obliteration of the village, with the death or expulsion

of its inmates, January 1, 1756, attested the trial of both fire-brand

and hatchet.

After a lump of coal found near Mauch Chunk, in 1791, by Ginther,

had been analyzed and pronounced as such by the savans

of Philadelphia, the following persons, Messrs. Hillegas, Cist,

Weiss, Henry, and others, associated themselves together, without

charter or corporation, as the "Lehigh Coal Mine Company,"

for the purpose of transporting coal to Philadelphia, in 1792.

They purchased land, cut a narrow road for the passage of a wagon

from the mine to the river, and sent a few bushels of anthracite

coal to Philadelphia in canoes or "dug-outs." None could

be sold; little given away. Col. Weiss, the original owner of

the land, spent an entire summer in diffusing huge saddle-bags

of coal through the smithshops of Allentown, Bethlehem, Easton,

and other places, From motives of personal friendship, a few persons

were induced to give it a trial, with very indifferent success.

Under the sanction of legislative enactment, some $20,000 was

expended to prepare tire Lehigh for navigation. No chore coal,

however, was carried down the stream until 1805, when William

Turnbull, by the aid of an ark, floated some 200 or 300 bushels

to Philadelphia. As the coal extinguished rather than improved

the lire, the great body of citizens refused to buy or make further

attempt to burn it, or be imposed upon by the black stuff.

Messrs. Rowland and Butland were the next to lease the mines,

and fail.

The success of Jesse Fell, of Wilkes Barre, in 1808, of burning

coal in a common grate, led two of the representative men of the

day, Charles Miner and Jacob Cist, to lease the Ginther mine in

1814, with a view of shipping coal to Philadelphia.

On the 9th of August of this year, the first ark-load of coal

started from Mauch Chunk. "The stream," writes Miner,

"wild, full of rocks, and the imperfect channel crooked,

in less than eighty rods from the place of starting the ark struck

on a ledge, and broke a hole in her bow. The lads stripped themselves

nearly naked, to stop the rush of water with their clothes. At

dusk they were at Easton, fifty miles."

The impetuous character of the river, untamed by art, and the

absence of any demand for coal, induced these pioneers to retire

from the Mauch, Chunk coal-mines. "This effort of ours,"

says Charles Miner, "might be regarded as the acorn, from

which has sprung the mighty oak of the Lehigh Coal and Navigation

Company."

In 1817, three energetic gentlemen, Josiah White, George F.

A. Hauto, and Erskine Hazard, profiting by each preceding failure,

originated the plan of floating coal down the inky, turbulent

current from Mauch Chunk to the Delaware by the aid of slackened

water.

From Mauch Chunk to Stoddartsville, not a single cabin rose

in the wilderness; the abandoned warrior's trail alone intervened.

In 1818, the Legislature of Pennsylvania empowered these gentlemen

as the "Lehigh Navigation Company," "to improve

the navigation of the river Lehigh" by constructing wing-dams

and channel walls along the more rapid and shallow portion of

the stream, so as to narrow and contract the current for practical

purposes. In October, 1818, "The Lehigh Coal Company"

built a road from the Lehigh to the old Ginther mine on Summit

Hill.

Arks of coal were carried down in the spring freshet; in the

summer months when water was low, bear-dams were constructed from

treetops and stones, "in the neighborhood of Mauch Chunk,

in which were placed sluice-gates of peculiar construction, invented

for the purpose by Josiah White, by means of which the water

could be retained in the pool above until required for use. When

the dam became full, and the water had run over it long enough

for the river below the dam to acquire the depth of the ordinary

overflow of the river, the sluice-gates were let down, and the

boats which were lying in tile pools above, passed down with the

artificial flood." [Henry's "Lehigh

valley."] Some 100 tons of coal thus found its way

down the Lehigh in 1818.

The partial success of a plan alike novel and unreliable, led

to a more systematic slack-water navigation from Mauch Chunk to

Easton, forty-five miles.

The people of Philadelphia, educated reluctantly in the use

and art of anthracite, finding this avenue from the coal-mines

inadequate to the demands of commerce, lent a hand to calm the

swift waters of the Lehigh for coal traffic. The Legislature of

the State, influenced by men able to bring greater political influence

to bear than this sterile region could then offer, granted to

Messrs. White, Hauto, and Hazard, the privilege of improving the

navigation of the Lehigh as far as White Haven; reserving, however,

the right of compelling the company to make a continuous

slack-water navigation to Stoddartsville, a sprightly lumbering

village, fifteen miles farther up the stream.

The Lehigh Coal and Lehigh Navigation Company were consolidated

in the spring of 1820. During this year 365 tons of coal, lowered

down the Lehigh in arks by some fifty dams, found its way to a

tardy market. A few years later, 400 acres of land was stripped

of its stately pines annually for the construction of the necessary

arks: these were manipulated into building material in Philadelphia,

while the iron was returned to Mauch Chunk for repeated use. This

destruction of wood, now seriously felt, and the waste of time

in building boats for a single trip, subsequently led to a more

practical method of navigation.

The slack-water (canal) navigation was opened to Mauch Chunk

simultaneously with the Delaware and Hudson Railroad, eastward

from the Lackawanna Valley, in 1829, to White Haven, in 1835.

As the Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company, already embarrassed

by the expensive dams they had built, could see no benefit to

accrue by the extension of their works to Stoddartsville, it asked

to be released from this particular part of the agreement, through

the same body that had so ungraciously imposed it. Objections

and remonstrances poured into the Legislature from Stoddartsville

and from almost every township in the county of Luzerne. Andrew

Beaumont, representing the expression and interests of Wyoming

Valley, with a strength and ingenuity for which he was ever remarkable,

interposed means to frustrate the wishes of the company. The matter

was finally compromised; the Navigation Company agreeing to erect

a single dam on the stream above Port Jenkins, and carry channel

walls and wing-dams from pool to pool for the passage of rafts

and logs from Stoddartsville, and build a gravity railroad over

the mountain from White Haven to Wilkes Barre. The Legislature

now withdrew or repealed so much of the former act as required

the completion of the slack-water navigation to Stoddartsville.

The valley of Wyoming ramifying with competing railways, gained

its first one by this scramble with a company with which its relations,

have subsequently become pleasant and profitable. This railroad

was begun in 1837.

A stream, rapid and treacherous as the Lehigh, passing for

miles through a mere fissure of vertical rock, bore restraint

with deceitful demeanor. Danger concentrated in every dam. A sudden

snow-thaw forced an infuriated volume down the Lehigh, January

8, 1839, at the expense of the company and their employees; on

the same day of the month in 1841, another thaw released the snow

from the mountain and swelled the torrent with loss of life and

property; the freshet, however, of 1862, resistless and unparalleled

in the extent of its ravages upon life and property, appalled

and smothered with a single wave every lock-house and its inmates,

every dam, boat, or bridge, attempting to interrupt its passage.

About 300 persons living along the river perished in that cold,

dark, memorable night.

The Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company, with but little left

but the bare stream exulting over its liberation, actuated by

humane and practical impulses as well as the wishes of the Lehigh

Valley inhabitants, who everywhere opposed the reconstruction

of the dams because of their danger, made the Lehigh a safer companion

by constructing along its berme bank, or the debris of

the canal, a locomotive railroad. While the immense forest around

White Haven, slashed into by the lumberman without regard to economy

or foresight, annually assured the road considerable traffic,

the gravity railway from Wilkes Barre, terminating here, could

not fairly compete with other routes diverging to the sea-board

from northern Pennsylvania.

LEHIGH AND SUSQUEHANNA RAILROAD.—Report of coal shipped

south, for week ending Dec. 31, 1868:

_

|

SHIPPED FROM |

WEEK |

TOTAL |

|

|

Tons/Cwt. |

Tons/Cwt. |

|

Harvey Brothers |

|

184 11 |

|

Lances' Colliery |

|

3,264 15 |

|

New England Coal Co |

|

1,129 02 |

|

Morgan Mines |

|

92 18 |

|

Parish & Thomas |

|

19,100 12 |

|

New Jersey Coal Co |

356 09 |

18,193 04 |

|

Gaylord Dunes |

|

245 01 |

|

Lehigh Luzerne Coal Co |

220 01 |

5,010 03 |

|

Lehigh & Susquehanna Coal Co |

|

15 10 |

|

Germania Coal Co |

|

20,866 08 |

|

Franklin Coal Co |

|

243 18 |

|

Wilkes Bane C. & I. Co |

4,772 01 |

335,544 17 |

|

Union Coal Co |

|

2,040 07 |

|

Mineral Spring Coal Co |

454 15 |

11,022 07 |

|

H. B. Hillman & Son |

103 19 |

2,768 14 |

|

Bowkley, Price & Co |

288 16 |

3,808 05 |

|

Wyoming Coal & T. Co |

286 14 |

4,375 16 |

|

Henry Colliery |

356 02 |

9,490 08 |

|

J. H. Swoyer |

|

5,405 08 |

|

Everhart Coal Co |

482 06 |

3.406 17 |

|

Morris & Essex Mut. Coal Co |

|

78 19 |

|

Shawnee Coal Co |

219 14 |

20,297 05 |

|

Delaware & Hudson Canal Co |

|

11,447 06 |

|

Pine Ridge Coal Co |

325 05 |

12,898 04 |

|

Consumers' Coal Co |

|

5,272 18 |

|

Albrighton Roberts & Co |

|

10,606 03 |

|

Other shippers |

197 18 |

12,469 03 |

|

|

|

|

|

Total Wyoming Region |

8,064 00 |

519,279 19 |

|

Total Mauch Chunk |

4,118 04 |

49,086 15 |

|

Total Hazleton |

49 10 |

332,817 06 |

|

Total Upper Lehigh |

2,389 12 |

141,499 06 |

|

|

|

|

|

Grand Total |

14,621 06 |

1,042,683 06 |

|

Corresponding week last year |

5,280 06 |

485,501 00 |

|

Increase |

9,341 00 |

557,182 06 |

Years of reconnaissance of the interposing mountain enabled

the engineers to descend with a, locomotive into the plains of

Wyoming triumphantly, as the Jewish ruler of old came down from

the sacred mount.

If there is grandeur in the bold outlines of precipice and

forest in the coal-fields of Pennsylvania, then the scenery along

the entire road is truly exhilarating, while the view in ascending

or descending the slope between Penobscot and Wilkes Barre is

singularly beautiful and unique. The broad expanse of Wyoming

Valley, with her dozen villages sleeping quietly in her bosom:—the

Susquehanna making a low bow and bend around Campbell's Ledge

at the head of the valley, dividing the rich bottom for twenty

miles before it gathers in a measure of its beauty and retires

from the eye at Nanticoke, and the green farms, dotted here and

there with quaint homesteads telling their story of strife and

skirmish in olden time, all make up a landscape rarely offered

to the eye of the traveler.

Steel rails, stretched over a great portion of the road,

impart a degree of security that must popularize it as a great

thoroughfare. In fact, the same far-seeing sagacity that this

pioneer company carried into the Lehigh Valley a quarter of a

century ago, to secure and develop anthracite, has led them to

make a railroad in such an excellent and thorough manner as to

be a marvel among American railroads, reflecting equal credit

upon the engineers and managers who matured this great enterprise.

John Leisenring, Esq., of Mauch Chunk, ably filled the united

position of superintendent and engineer of this road until the

summer of 1888. John P. Ilsley, a gentleman who enjoyed high consideration

as the superintendent of the Lackawanna and Bloomsburg for many

years, succeeds Mr. Leisenring in the superintendency of this

road.

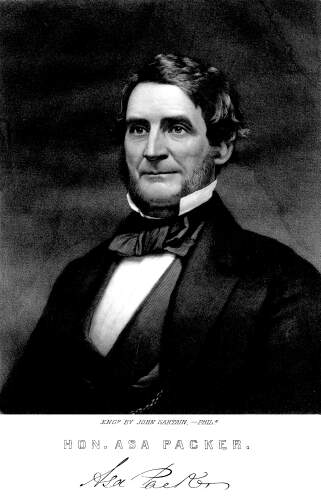

HON. GEORGE W. SCRANTON.

Col. George W. Scranton was too

universally known and beloved throughout the country to be overlooked

in a work aiming to do justice to men who have gained glory by

carrying reformation and development to the valley of which it

treats. The following biographical sketch of Colonel Scranton,

prepared especially for this volume, is from the able pen of Rev.

Dr. GEORGE PECK:— Col. George W. Scranton was too

universally known and beloved throughout the country to be overlooked

in a work aiming to do justice to men who have gained glory by

carrying reformation and development to the valley of which it

treats. The following biographical sketch of Colonel Scranton,

prepared especially for this volume, is from the able pen of Rev.

Dr. GEORGE PECK:—

Col. Scranton descended from John Scranton, who was

one of the colony who settled in New Haven in 1638. The Scranton

family was distinguished in the French and Revolutionary wars,

some of them as privates and others as commissioned officers.

Col. Scranton was born in Madison, Ct., May 11, 1811. At an early

period in life, he exhibited extraordinary qualities both of intellect

and heart. His opportunities for an education were embraced within

the privileges of the common school and two years' training in

"Lee's Academy."

In 1828, he came to Belvidere, N. J., and the first employment

he obtained was that of a teamster, for which he received eight

dollars per month. His great industry and general good conduct

excited the attention of business men, and he was soon employed

as a clerk in the store of Judge Kinney, where his great business

tact and winning management not long after gained him the position

of a partner in the concern.

On the 21st of January, 1835, Mr. Scranton was married to Miss

Jane Hiles, of Belvidere. After his marriage, he engaged in farming,

in which business he continued until 1839. At this time Mr. Scranton,

in partnership with his brother Selden, purchased the lease and

stock of Oxford Furnace, N. J., and, contrary to the predictions

and fears of their friends, they succeeded in the business, and

maintained their credit through the season of embarrassment to

business which followed the terrible crash of 1837.

In 1839, Mr. William Henry, being impressed with the advantages

of the manufacture of iron in the Lackawanna Valley, purchased

a large tract, including what was called Slocum Hollow, or what

is now the site of the city of Scranton. It contained "the

old red house," two other small dwellings, and a stone mill.

With the exception of a few acres of cultivated land, the tract

was covered with timber, a dense undergrowth, and a perfect tangle

of laurel.

The attention of the Scranton brothers was attracted to this

place, and, Mr. Henry not being able to comply with the conditions

of his purchase, they, in connection with other parties, in May,

1840, entered into a contract for the property.

The practicability of smelting ore by the agency of anthracite

coal, as yet was hardly established by successful experiment.

Two furnaces only now produced iron through heat generated by

anthracite, and that under embarrassments and in limited quantities.

The young company in which the Scranton brothers were the leading

spirits, was now to take a prominent part in a series of experiments

which were destined to contribute in no small degree to one of

the practical arts which has communicated a new and an undying

impulse to modern civilization.

The first experiment was made in 1841, and proved a failure;

the second was likewise unsuccessful, but in January, 1842, a

successful blast was made; others followed with increasing encouragement.

The practical difficulties in manufacturing iron by anthracite

were now considered as overcome, but the price that the triumph

had cost, few understood, and none would ever understand, so well

as George W. Scranton. He was the genius which presided over the

struggles of many months, and even years, of hope deferred and

of distrusting doubt which finally ended in complete success.

The scientific difficulties were no sooner overcome than financial

problems were to be encountered. They could make iron, but how

could they make it pay? The future city of Scranton was a straggling

assemblage of hut's, at a distance from every great market, and

without convenient outlet. These difficulties, with those arising

from want of funds, would have broken the spirits of ordinary

men, but our young adventurers, nothing daunted, resorted first

to one experiment and then to another, until they were able to

exclaim, with Archimedes, Eureka—I have found it.

A bootless effort to manufacture bar-iron and convert it into

nails finally gave way to the project of a rolling-mill for the

manufacture of railroad iron.

The great address of Col. Scranton succeeded with the leading

men interested in the New York and Erie Railroad in making the

contract to furnish rails needed by the road, at a lower rate

than they could be procured elsewhere, upon the condition that

the directors of the road would advance funds to enable the Scranton's

and company to proceed with the business of making rails. This

arrangement untied the Gordian knot of the Scrantons' financial

troubles.

Success in the iron business was not an occasion for Col. Scranton

to abate his energy in business. The manufacture of iron was but

one of his great business projects—it was but a part of a

great system, which, when fully carried out, was to reform the

entire business interests of this portion of the country, and

to change the whole face of society. His plan was to enlist capital

abroad, to concentrate it in the Lackawanna Valley, and then to

create outlets by railway east with North and South; and he lived

to see his project succeed.

Col. Scranton was not in the ordinary sense a politician, although

he was a thorough student of political economy. He had been an

old-line Whig, but for years had paid no attention to party politics.

There was one principle which he maintained against all opposers,

and that was, protection to home industry. Upon this issue

he was sent to Congress, in 1858, by a majority of 3,700, from

a district ordinarily polling 2,000 Democratic majority. He directed

himself incessantly to his favorite theme through the term, and

was elected a second time.

We are obliged to pass over a multitude of interesting incidents

in the life of Col. Scranton for want of space, and must now proceed

to a brief estimate of his character. In marking the character

of a great man, it will be found that it is only a few qualities

which distinguish them from other men and give them prominence.

Such is the fact with the great and good man of whom we are now

speaking. We begin with the great moral integrity of the man.

He was sincere—he was honest—his views were transparent.

When in Congress he could get the ear of the most ultra free-traders.

"Southern fire-eaters" would listen to his arguments

on protection and free labor. They would often say to him, "

Scranton, we can hear you talk, for we believe you are honest."

You might differ from his opinions, but you could not avoid believing

in the man. His zeal was that of conviction. His heart was upon

the surface—it was "known and read of all men."

His energy was inexhaustible. He never yielded to discouragements,

or acknowledged a total defeat. He sometimes failed, but always

tried again; and, if necessary, again and again, and triumphed

at last. He often spent the night in concocting a scheme, and

early dawn found him upon the path of its execution. Due time

usually brought success, but delay never staggered him. He was

fastened to his purpose, like Prometheus to the rock, and there

he hung, until mountains of difficulty melted away, and the sun

of success illuminated his path. A man of less hope would have

been despondent where he was confident, and one of a weaker will

would have fainted when he was firm as a rock.

Another trait of character holds the highest position. Col.

Scranton had the rare faculty of impressing his own ideas upon

the minds of other men. This power depends upon an assemblage

of qualities. An honest expression is essential to it. This expression

means confidence. A sympathetic nature. His earliest sympathy

in return, and sympathy exercises a marvelous control over the

judgment. Draw a man into sympathy with your feelings and wishes,

and you can lead him wherever you please. Blandness of manner

is another attribute of this great power. A pleasant countenance,

a happy face, has more power than logic. Good conversational powers

is of the first importance in this enumeration. There must be

definiteness of view, lucidness of description, brevity in the

statement of facts, naturalness and beauty in the illustrations,

command of language, perfect ease in manner, and an expression

of confidence both in your cause and in your success. You must