Baldwin Locomotive Works

Philadelphia, Pa., U.S.A.—1906

The Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe

Railway System

The Atchison,

Topeka and Santa Fe Railway System occupies a prominent position

among the great railway systems of the United States. The original

company was chartered on February 11, 1859, under the name of

the Atchison and Topeka Railroad Company. This name was changed

on March 3, 1863, to Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad Company.

The construction of the main line was begun in 1869, and the road

was opened for traffic on February 20, 1873. The original main

line extended from Atchison, Kansas, to the western boundary of

the state, and was 470.58 miles in length; the Company also operating

39.28 miles of branch lines. During the years 1874 to 1885, additional

extensions and branch lines aggregating 1357.90 miles were opened,

bringing the total length of main line and branches, on December

31, 1885, up to 1867.76 miles. The mileage of controlled roads

amounted to 878.99, the total mileage of the system thus being

2746.75 miles. The Atchison,

Topeka and Santa Fe Railway System occupies a prominent position

among the great railway systems of the United States. The original

company was chartered on February 11, 1859, under the name of

the Atchison and Topeka Railroad Company. This name was changed

on March 3, 1863, to Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad Company.

The construction of the main line was begun in 1869, and the road

was opened for traffic on February 20, 1873. The original main

line extended from Atchison, Kansas, to the western boundary of

the state, and was 470.58 miles in length; the Company also operating

39.28 miles of branch lines. During the years 1874 to 1885, additional

extensions and branch lines aggregating 1357.90 miles were opened,

bringing the total length of main line and branches, on December

31, 1885, up to 1867.76 miles. The mileage of controlled roads

amounted to 878.99, the total mileage of the system thus being

2746.75 miles.

During the next ten years the system was rapidly extended and

additional lines were acquired. In 1895, the mileage operated

as the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad was 4582.12; the

total mileage in the system including controlled roads, being

9321.29. The company was in the hands of receivers at this time,

and a complete reorganization being decided upon, a new charter

was secured, under the laws of Kansas, on December 12, 1895. The

new corporation took possession of the property on January 1,

1896, under the name of The Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway

Company. Since then additional lines have been acquired by the

management. On June 30, 1904, the total mileage embraced in the

published results of operations of The Atchison, Topeka and Santa

Fe Railway Company was 8300.92; the entire length of the system,

including roads controlled or owned jointly with other companies,

being 9269.20 Miles.

A double daily service is maintained between Chicago and San

Francisco, and through sleepers are run between Chicago, Los Angeles

and San Diego. The "California Limited," (train No.

3 west bound and train No. 4 east bound), which carries first

class passengers only, takes rank as one of the finest trains

in the world. The distance from Chicago to San Francisco is 2577

miles, the actual running time for train No. 3 being seventy-six

hours fifty-five minutes, representing an average speed, including

stops, of thirty-three and five-tenths miles per hour. The road

crosses three mountain ranges, where heavy grades are encountered.

The history of the motive power of the Santa Fe System is of

peculiar interest because, since the advent of the very heavy

locomotive, this road has played a leading part in its development.

The Baldwin Locomotive Works, has been closely identified with

this development, having supplied altogether since the beginning

of the road, some 1000 locomotives. These engines have been of

various types, and a brief review of the classes represented will

prove interesting.

The first locomotives constructed at the Baldwin Locomotive

Works for the Santa Fe System were four in number. They were built

in 1875, and were of the "American type," bearing the

road numbers, 44, 45, 46 and 47. These engines were representative

of a type generally employed at that time for working all classes

of traffic. They had cylinders sixteen inches in diameter by twenty-four

inches stroke, the driving wheels being fifty-seven inches in

diameter with a wheelbase of eight feet. The total wheelbase was

twenty-one feet nine inches. The boiler was of the crown bar wagon

top type with iron shell and a steel firebox. It was forty-six

inches in diameter and contained 144 tubes, two inches in diameter

and ten feet ten and three-eighths inches long. The firebox was

sixty-four and three-quarters inches long by thirty-four and one-half

inches wide. The grate area was fifteen and seventy-four one hundredths

square feet, and the total heating surface 926 square feet. These

engines weighed about 67,000 pounds, and carried about 42,000

pounds on their driving wheels. They were furnished with eight-wheel

tenders, having wood frames and tanks of 2000 gallons capacity.

Four locomotives of similar weights and dimensions were built

in 1877 and 1878.

During the following year, 1879, thirteen engines of the same

type, but of greater power, were supplied by the Baldwin Locomotive

Works, one of them, No.

91, being illustrated on page 4. These engines had

cylinders seventeen inches in diameter by twenty-four inches stroke.

The driving wheels were fifty-seven inches in diameter with a

wheelbase of eight feet, the total wheelbase being twenty-two

feet six and one-quarter inches. The boiler was of the wagon top

type, forty-eight inches in diameter; it contained 161 tubes,

two inches in diameter by eleven feet seven and one-half inches

long. The firebox measured sixty-four and fifteen-sixteenths inches

long by thirty-four and three-eighths inches wide. The grate area

was fifteen and six-tenths square feet. The firebox heating surface

was 103 square feet, and the tube heating surface, 975 square

feet; the total thus being 1078 square feet. These engines weighed

about 73,000 pounds in working order, the weight on the driving

wheels being 47,000 pounds. The tenders were of two sizes, that

of engine No. 91 having a 2500 gallon tank. The tank capacity

of some of the engines of this class was only 2200 gallons.

At this time construction was in progress on the New Mexico

and Southern Pacific division of the line. Previous to the completion

of the tunnel at Raton Pass, near the New Mexico State line, the

mountains were crossed by a "switch back" two and three-quarters

miles long, having grades of six per cent. (316.8 feet per mile)

combined with curves of sixteen degrees. To operate on this section

of track the Baldwin Locomotive Works in 1878, built a consolidation

locomotive of exceptional power, which at that date, was the largest

engine constructed in the practice of the Works. This locomotive

bore the road number 204, and was named "Uncle Dick."

It had cylinders twenty inches in diameter by twenty-six inches

stroke; the driving wheels being forty-two inches in diameter.

With 130 pounds steam pressure the tractive power would thus be

27,400 pounds. The boiler was straight top, built of steel throughout.

It was fifty-eight inches in diameter, and contained 213 tubes,

two inches in diameter and ten feet eleven and three-quarters

inches long. The firebox was 119 and one-eighth inches long by

thirty-three and three-eighths inches wide, with a grate area

of twenty-seven and four-tenths square feet. The total heating

surface was 1376 square feet, the firebox contributing 153 square

feet, and the tubes 1223 square feet. The first and third pairs

of driving wheels had plain tires, so that while the driving wheelbase

was fourteen feet nine inches, the rigid wheelbase was but nine

feet; the total wheelbase being twenty-two feet ten inches. The

engine had a saddle tank of 1200 gallons capacity on its boiler.

As used on the road a separate tender was also provided, having

an additional capacity for 2500 gallons. The total weight of the

engine was about 115,000 pounds, of which 100,000 pounds were

carried on the driving wheels. The illustration on page 5 and the reproductions of the

drawings on pages

6 and

7, clearly show the principal features of the design.

This locomotive did efficient work, hauling on an average seven

cars weighing, loaded, 43,000 pounds each, over the six per cent.

grade; the tender weighing about 44,000 pounds additional. On

one occasion nine loaded cars were hauled. In a day of twelve

hours, the "Uncle Dick" usually moved forty-six loaded

cars over the switchback from the north to the south side, bringing

back as many in return. In comparison two "American type"

locomotives coupled together could move only thirty-four cars

each way per day, so that the Consolidation engine was more than

equal in capacity to two standard road engines, the cost for fuel

and engine service being but little more than for one American

type locomotive.

During the years 1880 and 1881, forty-five Consolidation locomotives,

built at the Baldwin Works, were added to the equipment. Fourteen

of these engines were similar in many respects to the "Uncle

Dick," having the same wheel spacing and the same size boiler.

The saddle tank was omitted; the diameter of the driving wheels

was increased to fifty inches, and the piston stroke to twenty-eight

inches. The total weight was 107,000 pounds, the weight on driving

wheels being 91,800 pounds. The tank capacity was 3200 gallons.

Engine No. 132,

illustrated on page 8, represents the class.

The remaining thirty-one Consolidation locomotives referred to

were built for the Rio Grande, Mexico and Pacific Division. They

were lighter engines having cylinders seventeen inches in diameter

by twenty-six inches stroke; the driving wheels being forty-five

inches in diameter. The total weight was about 79,000 pounds of

which the driving wheels carried about 66,000 pounds.

In 1882, fifteen American type locomotives were built, these

being the heaviest engines of this type so far delivered to the

road. Their weight being about 78,000 pounds.

During the next few years, the necessity for heavier locomotives

for passenger traffic became fully realized; and in 1886 the Baldwin

Works began the building of ten-wheel engines for this class of

service. These were large locomotives for their day, having cylinders

nineteen inches in diameter by twenty-six inches stroke and fifty-eight

inch driving wheels. The boiler was straight, sixty inches in

diameter. It contained 227 tubes, two and one-quarter inches in

diameter, and thirteen feet one and one-half inches long. The

firebox measured eighty-two and fifteen-sixteenths inches long

and thirty-four and three-eighths inches wide, the grate area

being twenty square feet. The firebox heating surface was 143

square feet, and the tube heating surface 1742 square feet; thus

giving a total of 188S square feet. The driving wheels were grouped

on a wheelbase of fourteen feet six inches, the total wheelbase

being twenty-five feet eleven and one-half inches. These engines

weighed 114,500 pounds in working order, the weight on driving

wheels being 85,400 pounds. The tank capacity was 3500 gallons.

During the ten years following 1886, upward of 100 ten-wheel

locomotives, for both passenger and freight service, were supplied

to the System, in addition to a number of six-wheel switchers

and a few eight-wheel and Consolidation engines. During this period

steam pressures gradually increased from 130 and 140 pounds to

180 pounds, and in 1894 several eight-wheel and ten-wheel engines

were built to work at 200 pounds, an unusually high pressure for

single-expansion engines at that time.

The demand for more powerful locomotives was being met, and

forty-five Consolidation engines built in 1898 were representative

of the type then employed for heavy freight service. One of these

engines is illustrated

on page 9. Particular interest attaches to this design,

as these were the first locomotives built by the Baldwin Works

to have cast steel frames, which had largely been used by John

Player, then Superintendent of Motive Power, and which were specified

by him. The builders guaranteed to replace, within a period of

two years, all frames showing defective material or workmanship,

provided such frames were made by the Standard Steel Works. Frames

furnished by other makers and accepted by the company's representative,

were not subject to the guarantee. The cylinders of these engines

were twenty-one inches in diameter by twenty-eight inches. stroke,

the driving wheels being fifty-seven inches in diameter. The boiler

contained 1905 square feet of heating surface and twenty-nine

and one-quarter square feet of grate area, and carried a steam

pressure of 180 pounds. The total weight in working order was

156,130 pounds, of which 139,530 were carried on the driving wheels.

These engines were followed, in 1900, by forty heavier locomotives

of the same type, having larger boilers and thirty-inch piston

stroke.

Fifteen ten-wheel locomotives were constructed in 1899. The

illustration

on page 10, of engine 833, shows their general features.

The frames were of cast steel. These locomotives had cylinders

twenty inches in diameter by twenty-six inches stroke, the diameter

of the driving wheels being sixty-nine inches and the steam pressure

18o pounds; thus giving them a tractive power of 23,000 pounds.

The boiler was of the wagon top type, sixty inches in diameter.

It contained 262 tubes, two inches in diameter and fourteen feet

three inches long, the firebox being 102 inches long by forty

and one-quarter inches wide. The grate area was twenty-eight and

five-tenths square feet. The heating surface of the firebox was

167, and of the tubes 1942 square feet: thus giving a total of

2109 square feet. The total weight was 155,6io pounds, the weight

on driving wheels being 120,410 pounds. The tank capacity was

5000 gallons.

In June, 1901, Mr. J. W. Kendrick accepted the position of

third vice-president of the Santa Fe System. Mr. Kendrick's wide

experience in various branches of railway work enabled him to

deal successfully with the problems which, at this time, confronted

the various operating departments and especially the question

of selecting suitable motive power for handling the constantly

increasing traffic. From this time on the weight and power of

all classes of locomotives built for the Santa Fe rapidly increased,

and the advantages of using compound locomotives were clearly

recognized. The wide firebox was introduced on road engines, the

Santa Fe thus being quick to recognize its advantages. In 1901,

the Baldwin Locomotive Works built fifty Moguls for fast freight

service, thirty-five of which were compound and fifteen single

expansion, one of the latter is illustrated on page 11 Five compound

ten-wheel passenger locomotives, having Vanderbilt boilers, designed

for burning fuel oil, were turned out at about the same time;

and were followed by forty Prairie type locomotives which were

the heaviest yet constructed for passenger service and represented

a great advance over anything heretofore built for this road.

These engines are illustrated

on page 13. During 1902 and 1903, 103 similar locomotives,

with sixty-nine inch driving wheels, were built for fast freight

service, one of which is illustrated

on page 14.

In the meantime a rapid development in the weight and power

of heavy freight locomotives was taking place. One of thirty-five

compound Consolidation engines, built in 1902, is illustrated and described on page 15.

Early in the same year the Decapod engine, illustrated on page 17, was built

and the locomotive weight-record was again broken. This was the

first tandem compound built at the Baldwin Locomotive Works. It

was followed in the latter part of 1902, by fifteen Vauclain compound

"Mikado" type engines.

The policy which has characterized the Santa Fe during recent

years, toward improvements in locomotive construction, has been

a most liberal one. Realizing the advantages possessed by the

balanced compound locomotive, the road in 1903, ordered from the

Baldwin Works four Atlantic type engines constructed on this principle.

Mr. Kendrick was chiefly responsible for the introduction of these

engines, and he has since taken a leading part in their development

and successful operation; the Santa Fe having more balanced compound

locomotives in use than any other railway in the United States.

The number built to date for this road is 137. Of these ninety-six

are Atlantic type engines which are working through express traffic

between Chicago and La Junta, Colorado. The remaining forty-one

are of the Pacific type, and are used on the mountain divisions

of the system. In order to keep the wheelbase of the latter engines

within reasonable limits, all the pistons are coupled to the second

driving axle. As the cylinders are all in the same horizontal

plane, the inside main rods are built with a loop which spans

the leading driving axle.

The successful performance of the balanced compounds on the

Santa Fe has attracted wide attention and has resulted in the

extensive use of similar engines on other roads. The Atlantic

type engines have made some particularly fine runs, and have demonstrated

their ability, when handling heavy trains, to maintain high horse-power

and sustained speed.

An illustration and description of one of the Atlantic type

engines, which was exhibited at the St. Louis Exposition is presented on page

23, while the Pacific type is illustrated on page 25. The majority

of the latter class are equipped for burning oil.

In 1903, previous to the building of the balanced compound

Pacific type locomotives, twenty-six engines of similar type,

having single-expansion cylinders with piston valves, were constructed

at the Baldwin Locomotive Works. One of these engines is illustrated on the opposite page.

The heavy Santa Fe type locomotive illustrated on page 21, is one

of 141 built since 1903. The cylinders of these engines are similar

to those of the Decapod locomotive previously mentioned. The addition

of the trailing wheels gives them better curving qualities, especially

when running backward down grades. These engines, when introduced,

were the heaviest in the world. A large number are at work on

the western divisions of the system, and are using oil as fuel.

A similar locomotive, having single-expansion cylinders twenty-four

inches in diameter, was built in 1904; but those since constructed

have all, with one exception, been fitted with tandem compound

cylinders. The exception referred to is a locomotive built in

1905, which is equipped with a smokebox superheater and single-expansion

cylinders thirty-two inches in diameter; the boiler pressure being

140 pounds. This engine was constructed for experimental purposes.

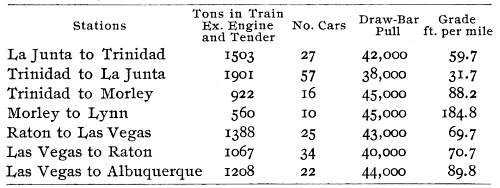

A series of tests on the hauling power of the Santa Fe locomotives

has recently been carried out, the draw-bar pull being measured

by a dynamometer car. The following table gives data secured on

the New Mexico Division. The tonnage behind the tender, number

of cars in the train, draw-bar pull and grade in feet per mile

are recorded; also the stations between which readings were taken.

With the starting valve open, the dynamometer registered as

high as 71,000 pounds draw-bar pull. This was maintained however,

for only brief periods of time.

Thirty-nine heavy six-coupled switching engines have been built

during the past year, and are illustrated

on page 27. These engines are representative of the

latest practice for this class of service. The principal dimensions

are presented with the illustration.

In building engines of various types for the same road it is

of great advantage to the builder as well as the railway company

to have the detail parts as far as possible interchangeable. In

the locomotives for the Santa Fe System, not only are the like

parts of each class accurately interchangeable, but the various

classes show a marked similarity in design and many parts are

interchangeable throughout several classes.

The Scott Special

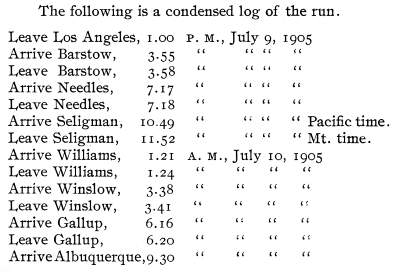

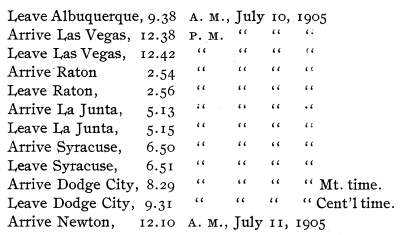

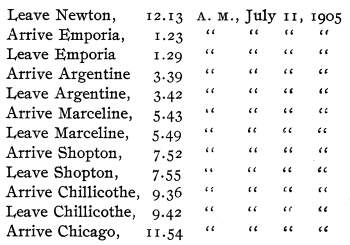

On several occasions exceptionally rapid runs have been made

over the Santa Fe System, the most recent being that of the Scott

Special, which left Los Angeles at 1 P.M.

on July 9, 1905, and reached Dearborn Station, Chicago, at 11.54

A.M. on July 11, covering 2265 miles in

44 hours 54 minutes, actual time, including all delays. This represents

an average speed of 50.4 miles per hour, and the feat stands without

a parallel in the history of long distance running. For practically

half the distance the run was made through mountainous country,

adding enormously to the difficulties encountered. Too much credit

cannot be given the management and all the employees concerned,

for this remarkable performance.

The run was made for the accommodation of Mr. Walter Scott,

a wealthy mine owner from Death Valley, California. Mr. Scott

first proposed the trip on Saturday, July 8, and 25 hours later

the special left Los Angeles. The price paid for the run was $5500.

The train was made up, of a baggage car, a diner, and a Pullman

sleeper, together weighing 170 tons. Nineteen locomotives were

employed, manned by 18 engineers and 18 firemen. In addition,

three helper engines were employed and an extra engine hauled

the train for a short distance, owing to an accident to the regular

train engine. The train was in charge of ten conductors, and the

running was supervised by the various superintendents over whose

divisions it passed.

Of the 19 locomotives, 17 were Baldwin engines. One was a ten

wheeler, four were of the Prairie type, with Vauclain compound

cylinders, three were of the Pacific type, and nine were of the

Atlantic type, with balanced compound cylinders. The latter class

handled the train between La junta and Chicago, where the fastest

time was made. The remaining two engines were Rhode Island ten-wheelers,

similar to the Baldwin engine of the same type. In addition to

these engines, a Baldwin compound Prairie type locomotive, with

sixty-nine inch wheels, hauled the train from Kent to Newton,

a distance of twenty-six miles, on account of the accident to

the train engine referred to above. The following summary gives

a general outline of the trip, showing the distance run by each

locomotive, average speed maintained and other items of interest.

Los Angeles to Barstow.—Engine 442, Baldwin ten-wheeler

(type illustrated on page 10),

Engineer John Finlay. Distance, 141.1 miles. Time 2 hours 55 minutes.

Delayed near Upland 3 minutes, hot tender journal; San Bernardino

6 minutes, water; Cajon 4 minutes, water. Helper engine, San Bernardino

to Summit, 25.5 miles Maximum grade, 116 feet per mile. Average

speed, including Stops, 48.5 miles per hour.

Barstow to Needles.—Engine 1005, Baldwin compound

Prairie type (illustrated on page 13).

Engineer T. U. Gallagher. Distance, 169.3 miles. Time, 3 hours

19 minutes. Average speed, 51 miles per hour. Average ascending

grade, Amboy to Goffs Summit, 52.4 miles, 37.6 feet per mile.

Maximum grade, 53 feet per mile.

Needles to Seligman.—Engine 1010, Baldwin compound

Prairie type. Engineer F. W. Jackson. Distance, 148.9 miles. Time,

3 hours 31 minutes. Average speed, 42.4 miles per hour. Average

ascending grade for entire distance, 31.9 feet per mile. Maximum,

95 feet per mile.

Seligman to Williams.—Engine 1016, Baldwin compound

Prairie type. Engineer C. Woods. Distance, 50.8 miles. Time, 1

hour 29 minutes. Average speed, 34.4 miles per hour. Grades generally

ascending. Maximum, 137 feet per mile.

Williams to Winslow.—Engine 485, Rhode Island ten-wheeler.

Engineer D. A. Lenhart. Distance, 92.2 miles. Time, 2 hours 11

minutes. Average speed 42.1 miles per hour. Grades undulating.

Maximum, 95 feet per mile ascending, 75 feet descending.

Winslow to Gallup.—Engine 1000, Baldwin compound

Prairie type. Engineer J. F. Briscoe. Distance, 128 miles. Time,

2 hours 35 minutes. Average speed, 49.4 miles per hour. Grades

ascending, average for entire distance 12.9 feet per mile. Maximum,

32 feet per mile.

Gallup to Albuquerque.—Engine 478, Rhode Island

ten-wheeler. Engineer H. J. Rehder. Distance, 157.8 miles. Time

3 hours 12 minutes. Average speed, 49.4 miles per hour. Grades

undulating. Maximum, 53 feet per mile.

Albuquerque to Las Vegas.—Engine 1211, Baldwin

Pacific type (illustrated on page 19).

Engineer Ed. Sears. Distance, 132.2 miles. Time, 3 hours. Average

speed 44 miles per hour. Helper engine, Lamy to Glorieta, 9.8

miles. Delayed Lamy, 7 minutes; Glorieta, 2 minutes. Maximum ascending

grade, 158 feet per mile.

Las Vegas to Raton.—Engine 1208, Baldwin Pacific

type. Engineer G. Norman. Distance 110.8 miles. Time, 2 hours

12 minutes. Average speed, 50.5 miles per hour. Delayed Springer,

4 minutes, water. Grades undulating. Maximum, 75 feet per mile.

Raton to La Junta.—Engine 1215, Baldwin Pacific

type. Engineer H. Gardiner. Distance, 104.5 miles. Time, 2 hours

17 minutes. Average speed, 46.2 miles per hour. Helper Raton to

Trinidad, 23 miles. Maximum grade, 175 feet per mile. Delayed

Trinidad, 2 minutes; Timpas, 3 minutes, hot box on diner.

La junta to Syracuse.—Engine 536, Baldwin Balanced

compound Atlantic type (illustrated

on page 23). Engineer David Lesher. Distance, 100.8 miles.

Time, 1 hour 35 minutes. Average speed, 63.7 miles per hour. Grade

descending, average 8.2 feet per mile.

Syracuse to Dodge City.—Engine 531, Baldwin Balanced

compound. Engineer H. Simmons. Distance, 101.6 miles. Time, 1

hour 38 minutes. Average speed, 62.2 miles per hour. Grade descending,

average 7.2 feet per mile. Delayed Hartland, 5 minutes, broken

triple on engine.

Dodge City to Newton.—Engine 530, Baldwin Balanced

compound. Engineer E. Norton. No. 530 knocked out a cylinder head

at Kent. Thence to Newton, 26 miles, train was hauled by Engine

1095, Baldwin Compound Prairie type, with sixty-nine inch wheels.

Engineer Halsey. Total distance, 153.4 miles. Time, 2 hours 39

minutes. Average speed, 57.9 miles per hour. Grades generally

descending, average 6.7 feet per mile. Delayed St. John, 7 minutes,

water and oil; Kent 4 minutes, changing engines.

Newton to Emporia.—Engine 526, Baldwin Balanced

compound. Engineer H. Rossiter. Distance, 73.1 miles. Time, 1

hour 10 minutes. Average speed 62.6 miles per hour. Grades light

and generally descending.

Emporia to Argntine.—Engine 524, Baldwin Balanced

compound. Engineer J. Gossard. Distance, 120.2 miles. Time, 2

hours 10 minutes. Average speed, 57.3 miles per hour. Grades short

and undulating, track almost level, Topeka to Argentine, 62 miles.

Lost about 14 minutes owing to reduced speed through yards, etc.

Argentine to Marceline.—Engine 547, Baldwin Balanced

compound, seventy-three inch drivers. Engineer A. F. Barnes. Distance,

108 miles. Time, 2 hours 1 minute. Average speed, 54 miles per

hour.. Road generally level.

Marceline to Shopton.—Engine 542, Baldwin Balanced

compound, seventy-three inch drivers. Engineer R. Jones. Distance,

112.8 miles. Time, 2 hours 3 minutes. Average speed, 55 miles

per hour. Grades, short and undulating.

Shopton to Chillicothe.—Engine 510, Baldwin Balanced

compound. Engineer C. Losee. Distance, 104.7 miles. Time, 1 hour

41 minutes. Average speed, 62.3 miles per hour. Grades undulating;

maximum, 31.68 feet per mile.

Chillicothe to Chicago.—Engine 517, Baldwin Balanced

compound. Engineer C. Losee. Distance, 134.3 miles. Time, 2 hours

12 minutes. Average speed, 61.0 miles per hour. Delayed at South

Joliet 4 minutes on account of hot crank pin on engine. Ran slow

through Joliet yard and into Chicago. About 18 miles of ascending

grade just east of Chillicothe, maximum 26.4 feet per mile. Otherwise

line is undulating with easy grades.

Some remarkable bursts of speed were made on this trip, especially

on the eastern end where the Balanced compounds were used. The

highest speed was recorded between Cameron and Surry, 2.8 miles,

Engine 510 covering the distance in 1 minute 35 seconds, the equivalent

of 106.1 miles per hour. On descending grades in the mountain

districts, speeds exceeding 70 miles an hour were occasionally

recorded.

Contents Page

|