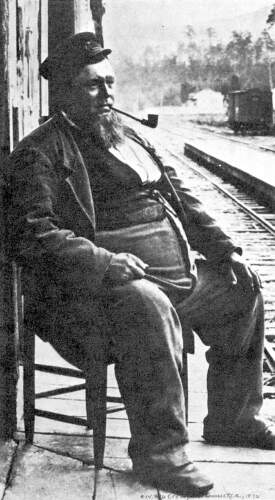

The Way Station Agent:

Suggesting An Epic

BY J.J. SHANLEY

FOR the great American epic we still strive and sigh and pray.

Illustrious literati despairingly cry out that the occasion has

not yet arisen, the subject is yet undiscovered, which would awaken

the inspiration of an American Homer, Virgil, Tasso, Milton or

Shakespeare. Paradoxical as it may seem, the occasion is continually

present, and we come in daily contact with the subject. He is

none other than the humble station agent at an intermediate railroad

point: the epitome of all railroad knowledge, the unfailing encyclopedia

of general information, the embodiment of the "strenuous

life," the concentration of responsibility and personification

of total self-effacement. An unswerving fidelity to duty is his

morning anthem, his noontime song and his evening hymn late into

the night.

The president

of our land, the most exalted of all potentates, is relieved of

much of his great responsibility by his cabinet, the supreme judiciary,

house and senate, governors, State legislatures, the thinking

citizen and the conscientious voter; the commanding general of

the army has his staff and numerous subordinates down to the tried

and true rank and file; the admiral has his captains, cadets,

marines, the men behind the guns and the stanch cruisers themselves;

the presidents of the mighty steel arteries of traffic have their

vice-presidents, general managers, general superintendents, division

superintendents, chief dispatchers, train masters, yard masters,

train men, down to the last, but not least, the man with the pick

and shovel and spike maul. But the agent at a way station, responsible

alike for lives and property, bends alone under his onerous burden.

He stands for all that is required from station master, agent,

chief clerk, bill clerk, baggage master, ticket agent, express

agent, telegraph operator and general factotum. The president

of our land, the most exalted of all potentates, is relieved of

much of his great responsibility by his cabinet, the supreme judiciary,

house and senate, governors, State legislatures, the thinking

citizen and the conscientious voter; the commanding general of

the army has his staff and numerous subordinates down to the tried

and true rank and file; the admiral has his captains, cadets,

marines, the men behind the guns and the stanch cruisers themselves;

the presidents of the mighty steel arteries of traffic have their

vice-presidents, general managers, general superintendents, division

superintendents, chief dispatchers, train masters, yard masters,

train men, down to the last, but not least, the man with the pick

and shovel and spike maul. But the agent at a way station, responsible

alike for lives and property, bends alone under his onerous burden.

He stands for all that is required from station master, agent,

chief clerk, bill clerk, baggage master, ticket agent, express

agent, telegraph operator and general factotum.

The station itself is regarded and utilized as a public building;

the agent is the chief personage in the immediate community, as

well as in the burgs and hamlets contiguous and tributary thereto.

He is at once the slave and idol of every man, woman and child

for miles around. He is the confidant of all the gossips and is

unwillingly cognizant of the dangling skeletons in the rural closets.

He is the butt of all the trainmen as well as the subject of complimentary

comments at every session of the "Stove Committee."

His time, early and late, seven days in the week and every day

in the year, is devoted to the company's interests and the welfare

of its patrons, with never a thought for himself, as he has no

affairs and is known to his children as that man who sleeps part

of the night at their house.

He must familiarize himself with the official classification

and all its supplements, with all tariffs, freight, passenger

and express, local, special and joint; with all divisions and

per cents for billing to connecting lines and foreign roads, a

task as herculean as the memorizing of Webster's Unabridged. He

must note contents and strictly comply with all information contained

in general orders, general notices, special notices, circulars,

etc., properly file them and eliminate or add to daily as requested.

He is easily recognized, for his characteristics proclaim him

a generic species of humanity. His gait is far from being a walk,

nor is it yet a run, but a sort of a compromise hurried jog. His

eyes assume an apparently vacant stare, since his mental concentration,

ever at rigid tension, will not permit of visual distraction,

but the habitual smiles which illumine the partial gloom of his

countenance are the never-failing indicators of his suavity, urbanity

and affability.

Mentally drop in on him of a morning and follow his routine

of daily duties. He arrives at Six A.M. and proceeds at once to

cut in his instruments with a genial "G-M" to the dispatcher.

His next move is to slick things up for the day. Oh, horrors!

he discovers that during the night marauders have gained an entrance

by forcing a rear window. He has no safe-the money and valuables

on hand after the last passenger train of the previous evening

he carries with him and will safely guard at the expense of his

life-but his tickets are strewn about in promiscuous confusion.

These he must count and arrange in numerical and station order.

Thus fretfully engaged, he is called to the telegraph table and

copies a "bunch" of orders for several trains in both

directions. Somebody rushes in saying he has fifty crocks of butter

and as many cases of eggs for the express east, due in a few minutes.

Besides the billing he must tag and label every piece. Somebody

else shouts from the freight-room that he has two or three loads

of H. H. (household) goods for which he demands an itemized bill

of lading to forward on the first mail. He sells tickets, checks

baggage, explains several times when the "eight o'clock train

is due," quotes the price of wheat, potatoes and other products

to inquiring farmers.

One of the trains has "laid down." The dispatcher

gets him again, "busts" all existing orders and fills

his table with a fresh lot, some to be signed for and others to

be handed on to trains going at full speed. Shippers are bringing

in shipments of every description, rates must be looked up and

waybills must be made out, with five to seven impression copies.

He delivers freight to consignors, runs from desk to table to

deliver orders and then realizes that the fast mail is about due.

Frantically he rushes to the post-office for the pouch, and the

twitching of his hands and occasional nervous strides to and fro

are the only perceptible evidences of his impatience at the dignified

deliberation of "Uncle Sam's" representative. The bag

is finally ready; he snatches it, flees as with a fear, and has

barely suspended it on the crane when the train goes thundering

by.

The morning "local" now pulls up and unloads sufficient

to fill an exposition building. Each article must be tallied and

checked off by the agent, besides noting with the keenness of

a detective the "overs, shorts and damaged." He also

sees to loading and checking in of all freight going forward,

and reseals all cars which have been opened. The dispatcher again

wants him and throwing the armful of waybills on the desk he flies

now here, now there and keeps on the jump until the passenger

trains, "locals" and three or four through freights

have pulled out. He has been undoubtedly "rattled" to

a certain extent but his habitual self-restraint saves him from

it "going up in the air" entirely. Nevertheless with

tingling fingers pushed up through his scant locks and cold perspiration

on his brow, he wonders if perchance he made a "miscue"

in delivering any of his orders.

He answers his "call" once more and receives a W.

U. message collect, for a person who lives just on the verge of

the mile delivery limit. He asks to be out the required time,

and his pace for that mile would arouse envy in a professional

sprinter. He finds his man and presents the telegram, naming the

charges. The recipient takes it, twirls it over two or three times

and asks the agent if he has read it. The latter replies with

unperturbed countenance that he merely transcribed it during transmission

and the privacy of telegrams is inviolable. Whereupon the person

thanks him, saying that he will hand in the change the next time

he is down to the station, and the agent returns, intuitively

knowing that this forty-three cents will be entered on the loss

side of his individual cash account. When he enters the office

he hears his call as usual; the dispatcher warmly asks him where

in Halifax he has been and how long he thinks the company will

endure having the road tied up to suit his convenience. Another

batch of orders follows with the accompanying hustle of signing,

grabbing and away.

Next comes a message from the superintendent directing him

to proceed at once to a point about two miles distant, where live

a couple of people of easy, conscience who, a day or two previously,

had appropriated several hogs which had escaped slightly injured

from a derailed car. He again arranges to be absent. His instructions

are to collect at the rate of four and one-half cents per hundred

and to arrive as nearly as possible at actual weight; pushing

along he evolves a new meaning peculiar to himself from the railroad

expression of "being on the hog." When he reaches his

destination he finds the hogs already slaughtered and dressed

or rather undressed, as there is nothing on them, or in them for

that matter. With the cajolery of a Russian and the adroit directness

of a Japanese diplomat he comes to a satisfactory understanding

with the embryonic Armours and returns to the station complacently

happy.

He locates the trains and says "S. F. D." (stop for

dinner) twenty minutes. "Hurry back," is the response.

Just think of it, ye epicures, get thee home, dine in the meantime,

and hurry back, all in twenty minutes. Through the afternoon and

until late into the evening the hours are but a repetition of

the foregoing multifarious duties with their attendant vexations,

until he finally "cuts out" for the night.

The Way Station Agent may have aspirations for a broader field

of action, and as he is usually a man of parts, he may sometimes

long for the social enjoyments of a more metropolitan sphere,

but he is as much of a fixture as his semaphore, and while wending

his way homeward and gazing around upon the limited horizon of

his circumscribed environment, only the certainty of duty faithfully

performed can cause his heart to throb with jubilant pulsations.

"Let not ambition mock their useful toil, Their homely

joys, and destiny obscure."

Stories Page | Contents Page

|