|

COMING OF THE FIRST CONDUCTOR.

Eben E. Worden was the first Erie conductor. He was a slight,

delicate young man, and was noted for his polite manners. He had

been a member of the firm of Thomas & Wordan, who had a contract

for a section of the first grading of the railroad in 1840, the

cut through Piermont Hill being a part of their work. The Railroad

Company being in financial straits, the firm lost money. According

to the reminiscences of W. H. Stewart, it was understood that

one John S. Williamson, who had influential friends in the Company,

was to be made conductor as soon as the road was opened. Williamson

lived at New York. In consequence of Worden having been unfortunate

in his dealings with the Company, Superintendent H. C. Seymour

appointed him to be the conductor on the opening of the railroad

to Goshen. He came from Cayuga County. He had been a contractor

on the Erie Canal, and had a large claim against the State, which

was disallowed. He then took the contract on the Erie, in 1840.

He remained with the Erie two years as conductor, when broken

health compelled him to resign. He died of consumption in the

fall of 1844, and was buried at Sennott, Cayuga County. He married

a Miss Smith, of Goshen, but left no family. (The author made

diligent effort to obtain a portrait and biographical data of

this first Erie conductor for reproduction here, but was unable

to obtain either, much to his regret.)

The appointment of Worden as conductor created a great deal

of feeling among the friends of Williamson, and they not being

disposed to let the matter pass without an effort to secure him

the conductorship, in spite of the fact that Worden had it, Williamson

was offered the place of Receiver of Freight on the New York dock,

as a compromise. He accepted the offer, but with the understanding

that when the Company employed another conductor he should be

the man. Capt. A. H. Shultz, or Capt. "Aleck" Shultz,

as he was more generally known, had command of the steamboat that

ran between Piermont and New York, in connection with the railroad.

A man named Evans was ticket clerk on the boat. This man evidently

had influence with Captain Shultz, and Captain Shultz must have

been influential at railroad headquarters, judging from what happened.

Evans had a relative by marriage named Henry Ayres, who was working

for the Harlem Railroad Company. The Erie had to have a freight

conductor, and Evans put in a word for Ayres to Captain Shultz,

and Captain Shultz talked it up at the Erie offices, and Ayres

was chosen as conductor to take charge of the freight train on

the road between Goshen and Piermont, thus becoming the second

conductor on the Erie. This appointment caused another disturbance,

and the friends of Williamson tried to have Ayres' appointment

reconsidered, but without success.

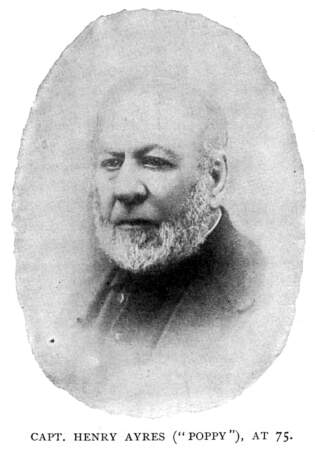

This Conductor Ayres became part of the history of the Erie,

for he was more than thirty years the dean of the fraternity of

Erie conductors, and, as "Poppy" Ayres, was known the

country over for years after he ceased to be a railroad man. Henry

Ayres was a native of Boston. In 1820 he was in the United States

Army, and was under General Eustis when that officer took possession

of St. Augustine, Fla., July 4th of that year. In the spring of

1837 he began work as a conductor on the Harlem Railroad, running

from New York to Morrisania, and in September, 1841, commenced

running on the Erie. He continued as conductor until May, 1869,

when he left the road, and became proprietor of the Central House

at Owego, to which place he had removed in 1848. He was subsequently

for a time United States Mail Agent on the Erie Railway, and was

afterward in the service of the Company at Elmira. When he left

the road he was retired on half pay, which continued until his

death.

Captain Ayres,

whose title of Captain was given to him by his friends many years

ago, was one of the most genial of men, and his fund of good humor

was inexhaustible. He was known affectionately everywhere as "Poppy"

Ayres. He was a very large man, weighing about 300 pounds. He

had to squeeze his way through the car doors sidewise. In winter

he wore a fur-trimmed overcoat and coon-skin cap. He died at Owego,

October 5, 1880, aged eighty years, leaving a wife, and a son

and daughter by a former marriage. Captain Ayres,

whose title of Captain was given to him by his friends many years

ago, was one of the most genial of men, and his fund of good humor

was inexhaustible. He was known affectionately everywhere as "Poppy"

Ayres. He was a very large man, weighing about 300 pounds. He

had to squeeze his way through the car doors sidewise. In winter

he wore a fur-trimmed overcoat and coon-skin cap. He died at Owego,

October 5, 1880, aged eighty years, leaving a wife, and a son

and daughter by a former marriage.

The history of the Erie is rich in reminiscences of Captain

Ayres, of which these are samples:

AN UMBRELLA THAT CAME BY TELEGRAPH.—In the summer of 1849,

a worthy old lady living at Lordville, in the Delaware Valley,

resolved to make a trip to New York, where she had relatives,

and see the great sights of Gotham. She had been out of sight

of her native place but once in all her life, and that was when

she went one time "down the river" on a raft with her

husband. For her New York trip she had boxes and bundles a-many.

Among these belongings was an ancient umbrella, a family relic.

It is presumed that she enjoyed her visit, but she had much tribulation

on her return trip. In coming up the Hudson River on the steamboat,

she became so nervous from fear that the cars would leave Piermont

without her that she forgot all about her much-prized umbrella,

and left it on the boat. She did not miss it until the train had

reached Cochecton, which was well on toward her own stopping-place.

"Poppy" Ayres was the conductor. In passing through

the cars after the train left Cochecton, he saw the old lady swaying

back and forth in her seat, wringing her hands and making a great

ado.

"What's the matter, mother?" the kindly conductor

immediately asked her "Are you sick?"

"No. Not sick!" sobbed the old lady. "But I've

left my umbrell' (sob) aboard the steamboat! That umbrell' (sob)

has been in our family fer more'n forty year (sob), and now it's

gone! Oh, oh, oh! That's worse than (sob) bein' sick 1 Boo-o-o-o,

woo-o-o-o!"

"Oh, mother, mother" said Poppy, consolingly patting

the old lady on the back. "Don't cry! We'l lget your umbrella

for you. We'll send for it on the telegraph. It'll be here in

a minute or two."

The old lady cheered up instantly. She dried her tears, but

could not disguise the surprise the conductor's assurance gave

her. Ayres reached up, took hold of the bell-rope, then only a

recent adjunct, and one that "Poppy" had himself introduced,

as is told elsewhere. He wriggled the rope, assuming a theatrical

and mysterious manner, and passed on, leaving the old lady gazing

at the rope in open-eyed wonderment. The telegraph had not, as

yet, been put in operation, but a line was in course of construction

through that country, and the talk of the people was of that as

much as it was of the railroad, which had itself only just come

among them. Conductor Ayres knew that if the old lady had left

her umbrella on the steamboat he would find it in the baggage-car,

for it was the rule for the stewards of the boat to go through

the saloons after passengers had left them at Piermont, and if

any articles had been left there by absent-minded travellers they

were taken on board the train and placed in the baggage-car, that

they might be restored to their owners. So Poppy Ayres went into

the baggage-car, found the umbrella, and, taking it under his

arm, started back through the train. When he came to the car where

the old lady was, he took it to her and exclaimed, as if in great

triumph:

"There, mother! I told you we could get your umbrella

by telegraph! And here it is!"

The owner of the umbrella was speechless with joy for a time

over the recovery of the prized relic. She looked at it, and then

gazed at the smiling conductor. At last she exclaimed:

"For the land sakes alive! Who'd ever 'a' thunk it? I've

heern o' letters and papers bein' sent by telegrapht, but who'd

'a' thunk they could send umbrell's?"

And in the exuberance of her joy she rose quickly to her feet;

threw her arms around Poppy Ayres's neck, and hugged and kissed

him repeatedly before he could release himself, much to the delight

and amusement of the other occupants of the car.

HE SUED "Poppy" AYRES.—One day, in the summer of

1856, a fussy old gentleman, named John Beebe, bought a ticket

at Newburgh for Addison, Steuben County, N. Y. When the train

he was on reached Deposit, which was far less than half the way

on his journey, Mr. Beebe was tired, and he got off the train

and remained over night at that place. Next morning he resumed

his journey on the emigrant train. This train was not pleasing

to Beebe, but he stuck to it until it got as far as Great Bend,

Pa. At that station he deserted the emigrant train and waited

for the day express. The day express was a "swell" train

at that day, and its conductor was "Poppy" Ayres. He

passed through his train after leaving Great Bend, and came to

traveller Beebe, who handed up his ticket. The conductor glanced

at it and handed it back to the passenger.

"Ticket ain't good!" said "Poppy" Ayres.

"Isn't good?" exclaimed Mr. Beebe, flaring up. "I'd

like to know why it isn't good."

Been punched once for this division," replied Poppy.

I don't care if it's been punched for this division, or that

division, or the other division," retorted the excited passenger.

I I I paid for it, and I'm going to ride on it."

"You'll have to pay your fare on this train," said

the conductor, quietly.

"I'll bet you I won't!" declared Mr. Beebe, with

much emphasis. "You'll take this ticket or nothing."

"Poppy" Ayres would not take the ticket, and Mr.

Beebe would not pay his fare, so the train was stopped and the

stubborn passenger was put off. That did not cool him down a particle,

however. He brought suit in Broome County, not against the Company,

but against Conductor Ayres, to recover damages for being put

off the train. Judge Balcom, who was afterward called to act in

far more serious but much less creditable Erie litigation, heard

the case, and directed a verdict for the plaintiff. The jury gave

him a judgment for $250 against "Poppy" Ayres. As the

conductor had simply carried out the orders of his superiors in

ejecting Beebe from the train, it is to be presumed that the Company

made good the judgment against him. He never would say whether

such was the fact or not. At any rate, the case was not appealed.

It may be that this was because the Company had then pending an

Appeal in the case of Ransom against the New York and Erie Railroad

Company, the lower courts having awarded the plaintiff, who had

been injured by a train at Chemung, a judgment of $15,000. If

the Company was awaiting the result of that case before trying

its chances in any other appeals it acted wisely, for a few weeks

after the Ayres verdict the Ransom judgment was affirmed. Ransom

had been hurt July 4, 1853. Interest and costs increased the original

amount to $20,000.

Erie Page | Stories Page

| Contents Page

|