|

A LITTLE JOURNEY INTO

ARKANSAS.

BY JOHN H. RAFTERY.

It has been my fortune during the past year to spend some months

in the famous fruit regions of Michigan and therefore to know,

at first hand, something of the native resources of that district

and something of the incessant endeavor which has made it famous.

The climate is rigorous in spring and winter, often harsh even

in summer, and in the autumn as whimsical as a woman's moods.

Its beauty—and it IS beautiful—has in it the sting,

the poignancy, the threats of the moist winds that whip from the

great inland seas which almost surround the state, teasing the

nights with chilly shrillings even in summer, and withering the

face of nature in the autumn before the Indian summer days of

more southerly states have felt the tang of the first frost.

And yet the

huddled farmers of that widely praised fruit region of Michigan

cling to their small holdings of land with jealous devotion. Something

of the Dutch thrift is in their blood; they toil and figure and

lay awake o' nights, but they seldom sell out. They have at times

pests of insects and visitations of blight which destroy some

of their profits, but they stick manfully to their tasks and hold

values high. Living is costly, for lumber and coal, cattle and

corn are scarce and there the winter bites with fangs of steel.

Fifty dollars will not buy a good acre of fruit land in the Michigan

belt. The canny husbandmen are wedded to their homes, their farms.

They have through the generations and through years of harsh experiences,

adapted themselves to the hard accessories of their northern climate

and they are happy, prosperous and contented. I think it is well

for then that they are a home-keeping race. And yet the

huddled farmers of that widely praised fruit region of Michigan

cling to their small holdings of land with jealous devotion. Something

of the Dutch thrift is in their blood; they toil and figure and

lay awake o' nights, but they seldom sell out. They have at times

pests of insects and visitations of blight which destroy some

of their profits, but they stick manfully to their tasks and hold

values high. Living is costly, for lumber and coal, cattle and

corn are scarce and there the winter bites with fangs of steel.

Fifty dollars will not buy a good acre of fruit land in the Michigan

belt. The canny husbandmen are wedded to their homes, their farms.

They have through the generations and through years of harsh experiences,

adapted themselves to the hard accessories of their northern climate

and they are happy, prosperous and contented. I think it is well

for then that they are a home-keeping race.

I left Michigan in September, when the winds that rush hither

and thither across the peninsula have in them those buffetings

that make the bones ache and numb the fingers that would dally

with rod and reel. And within a few days I was on the southern

slope of the Boston mountains, in Crawford county, Arkansas, with

a pungent south wind blowing in my face and the wine of a matchless

autumn day stirring my blood. I have lived in Colorado, where

the mountains, vast and cold, in winter look like the rust-brown

fragments of iron desolation; I have fished in Tahoe in the Sierras

in the fall when the whole world seemed plumed with mourning timbers,

scarred with rushing mountain rivers and innocent of drill or

plow. I have stood at the measureless rim of that "inferno,

swathed in soft celestial fires," in Arizona, where veteran

travelers are mute and terrified in the presence of such pitiless

immensity. And in all of these mountains, in all the splendors

of their titanic size, in all the mysteries of their wan abysses,

I have never said "Here could be my home!"

But that is

what one says, standing upon the verdure-clad mountains of Northwestern

Arkansas, looking across the billowing plateaus of Crawford, Washington,

Benton and Sebastian counties. There is a winsome tenderness about

that region that is not all of the atmosphere, nor all of the

magical beauty of the scenery, nor yet all of the bourgeoning

sod, but, I guess, some subtle blending of all these, some feat

of Nature's necromancy, some spirit of the earth, the sky and

air that springs, sun-touched, from the matchless alembic of those

hill-encinctured vales. Here could be my home, you say, looking

from hill to hill through the gold-gray haze of the gentle Indian

summer; here could be my home, you think, when the frost is in

the dry, brisk air of winter like courage in the nostrils of a

boy, and the hills stand 'round about the sheltered valleys so

that you forget the blight of the blizzards in the northern states;

this could be my home, you say , again in spring, when the sap

is stirring and again when the golden days of summer come crowding

on with fruits and flowers and grains that are ripening before

the frost is melted in the backward regions of the north. But that is

what one says, standing upon the verdure-clad mountains of Northwestern

Arkansas, looking across the billowing plateaus of Crawford, Washington,

Benton and Sebastian counties. There is a winsome tenderness about

that region that is not all of the atmosphere, nor all of the

magical beauty of the scenery, nor yet all of the bourgeoning

sod, but, I guess, some subtle blending of all these, some feat

of Nature's necromancy, some spirit of the earth, the sky and

air that springs, sun-touched, from the matchless alembic of those

hill-encinctured vales. Here could be my home, you say, looking

from hill to hill through the gold-gray haze of the gentle Indian

summer; here could be my home, you think, when the frost is in

the dry, brisk air of winter like courage in the nostrils of a

boy, and the hills stand 'round about the sheltered valleys so

that you forget the blight of the blizzards in the northern states;

this could be my home, you say , again in spring, when the sap

is stirring and again when the golden days of summer come crowding

on with fruits and flowers and grains that are ripening before

the frost is melted in the backward regions of the north.

Now, if I happened to be a Michigan fruit farmer, or any kind

of a farmer, I'd be tempted to sell out, pack up and come to Arkansas,

and the wonder of it all is that, in spite of its almost unequaled

climate, its rare beauty and absolutely incomparable fructivity,

these northwestern counties of Arkansas have not yet reached the

tenth part of their possibilities, have not known one-seventh

of the population which their teeming, fields, ore-charged mountains

and matchless fruit lands could well sustain. In Crawford county

alone there are 400,000 acres, and if the 22,000 people living

within its borders were scattered equally throughout its expanse,

there would be but one person on every twenty acres. Similar conditions

prevail in the other counties of this singularly beautiful region,

and even now the great volume of emigration which passes annually

over the Frisco System to the western and southwestern wonderland,

of Oklahoma, Texas and Indian Territory pauses not for the no

less salubrious, equally fertile but far more beautiful farm and

orchard lands of Northwestern Arkansas.

It has been said that in Southern California they sell climate

by the acre and certainly they get good prices for it. In the

rich farming districts of the north you buy land without reference

to atmospheric conditions. In the semi-arid regions you must supply

water for agriculture by artifice. In the cold regions you must

combat the rigors of nature by artifice, too. But in Arkansas,

especially in those upper altitudes, those radiant reaches of

the hill-district, you will find a climate that, is not surpassed

in America, a soil that has no superior for fruit, for grain and

for every flower, forage, feed or fabric plant that grows in the

temperate and semi-tropic zones. When you buy an acre of land,

the cubic acre of atmosphere that is "thrown in" is

neither the brass-blue rainless air of the desert nor the storm-laden,

marrow-piercing climate of the north.

I'm not sure

that the average farmer "figures" much on climate. The

masculine fruitraiser is apt to be satisfied if he nourishes either

by the sweat of his brow or the frost-bite of his ears. But if

he can flourish with less labor and without encountering the frozen

face, what's the use of remaining a martyr? Benton county, Arkansas,

for instance, is said by fruit experts to be capable of producing

more apples of a uniformly high quality, than any similar area

in the United States. And yet it has not attained more than one-tenth

of its limitations in this single particular! Last year the county

marketed 9,000 crates of strawberries, delivering them in northern

markets from two weeks to two months earlier than rival sections

of even the South, and at a profit not excelled in any berry-raising

district. The county might just as easily have marketed ninety

thousand crates, because the demand for the early strawberries

of Arkansas is unlimited, their fame is established and the accessible

markets are expanding more rapidly than the supply. Land is more

than fifty per cent cheaper, on an average, than the fruit lands

of Michigan; the natural precipitation of moisture is greater

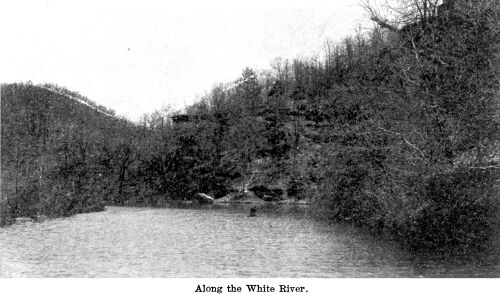

than in the fruit belt of Texas, the number of rivers and springs

of pure water is greater than in any other Southern state, and

yet the climate is as equable and as healthy as in the sun-bathed

valleys of the Red river. I'm not sure

that the average farmer "figures" much on climate. The

masculine fruitraiser is apt to be satisfied if he nourishes either

by the sweat of his brow or the frost-bite of his ears. But if

he can flourish with less labor and without encountering the frozen

face, what's the use of remaining a martyr? Benton county, Arkansas,

for instance, is said by fruit experts to be capable of producing

more apples of a uniformly high quality, than any similar area

in the United States. And yet it has not attained more than one-tenth

of its limitations in this single particular! Last year the county

marketed 9,000 crates of strawberries, delivering them in northern

markets from two weeks to two months earlier than rival sections

of even the South, and at a profit not excelled in any berry-raising

district. The county might just as easily have marketed ninety

thousand crates, because the demand for the early strawberries

of Arkansas is unlimited, their fame is established and the accessible

markets are expanding more rapidly than the supply. Land is more

than fifty per cent cheaper, on an average, than the fruit lands

of Michigan; the natural precipitation of moisture is greater

than in the fruit belt of Texas, the number of rivers and springs

of pure water is greater than in any other Southern state, and

yet the climate is as equable and as healthy as in the sun-bathed

valleys of the Red river.

The railroad, educational and social progression of this portion

of Arkansas are already years ahead of the tributary population.

There are colleges and academies at Bentonville, Ropers, Pea Ridge,

Mason Valley, Siloam Springs, Gentry and other towns of Benton

county and more than a dozen daily newspapers. A hundred public

and private schools offer educational facilities that would not

be overtaxed by an immediate access of 25,000 people.

It is not

easy to understand why emigrants seeking for cheap lands of proved

fructivity will "jump over" a region so singularly blessed

with every gift of nature, to go further and perhaps fare worse.

If you would write to Mr. Berkely Neal, Van Buren, Crawford county,

he would send you a mass of information well calculated to astonish

these who do not know that the berry farmers around Van Buren

last year netted more than $15,000 from the strawberries sold

in that town alone. There are as yet no authentic figures as to

the quantities of apples, peaches, pears, cherries, grapes and

other small fruits raised in these northwestern counties of the

state, but it is a matter of record that at every exhibition,

fair, exposition or horticultural display in which the growers

of this section have exhibited the examples shown have outranked

all others in point of QUALITY. In perfect texture, in color,

in flavor, in freedom from scars and diseases, the Arkansas apple

is, par excellence, the champion of the world. It is not

easy to understand why emigrants seeking for cheap lands of proved

fructivity will "jump over" a region so singularly blessed

with every gift of nature, to go further and perhaps fare worse.

If you would write to Mr. Berkely Neal, Van Buren, Crawford county,

he would send you a mass of information well calculated to astonish

these who do not know that the berry farmers around Van Buren

last year netted more than $15,000 from the strawberries sold

in that town alone. There are as yet no authentic figures as to

the quantities of apples, peaches, pears, cherries, grapes and

other small fruits raised in these northwestern counties of the

state, but it is a matter of record that at every exhibition,

fair, exposition or horticultural display in which the growers

of this section have exhibited the examples shown have outranked

all others in point of QUALITY. In perfect texture, in color,

in flavor, in freedom from scars and diseases, the Arkansas apple

is, par excellence, the champion of the world.

Passing southward into Washington county, with its 890 square

miles, the paucity of population in this wondrous region becomes

even more apparent and more astonishing. There are today more

than twenty-five thousand acres of Government lands in this county

open to homesteading, and in most cases bearing timber that is

worth twice the initial cost of acquiring and perfecting a title.

Upon its alluvial soil every cereal known to the temperate latitude

will prosper. Washington county is called the "grain belt"

of Arkansas because its fields will yield 50 bushels of corn,

20 bushels of wheat or 40 bushels of oats on every acre so planted.

In addition to its cereal productivity there are thousands of

acres of fruit lands as perfectly adapted for orchards as can

be found in the world. Concord, Norton's Virginia, Neosho and

Delaware grapes seem to surpass the best performances of their

native soils when once installed in the favorable vinelands of

Washington county.

Sebastian county,

further south, is richer in mineral endowments than any similar

area of the southwest. Fort Smith, its chief city, has a population

of more than 20,000. It is a hive of factories and founderies,

and yet one of the comeliest, cleanest manufacturing towns in

this country. The coals of Sebastian county, like the apples of

the state, excel all others in quality. They are smokeless. The

Quartermaster General of the United States officially reports

that the heating capabilities of Sebastian county coal are from

25 to 100 per cent greater than any other in the world with the

exception of the Pocahontas coal of West Virginia. The available

supply, it not inexhaustible, is so vast that the output of its

mines has made no perceptible impression upon the deposits already

surveyed. But the mineral wealth of this county has subtracted

nothing from its agricultural and horticultural endowments. It

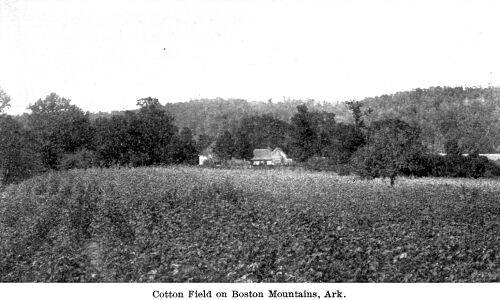

yield cotton and wheat, corn and potatoes, of the highest quality

and the greatest profusion. It has true forests, including almost

every timber known to the middle timber regions. Its topography

is the warrant for, and the explanation of, its high sanitary

rating. Sebastian county,

further south, is richer in mineral endowments than any similar

area of the southwest. Fort Smith, its chief city, has a population

of more than 20,000. It is a hive of factories and founderies,

and yet one of the comeliest, cleanest manufacturing towns in

this country. The coals of Sebastian county, like the apples of

the state, excel all others in quality. They are smokeless. The

Quartermaster General of the United States officially reports

that the heating capabilities of Sebastian county coal are from

25 to 100 per cent greater than any other in the world with the

exception of the Pocahontas coal of West Virginia. The available

supply, it not inexhaustible, is so vast that the output of its

mines has made no perceptible impression upon the deposits already

surveyed. But the mineral wealth of this county has subtracted

nothing from its agricultural and horticultural endowments. It

yield cotton and wheat, corn and potatoes, of the highest quality

and the greatest profusion. It has true forests, including almost

every timber known to the middle timber regions. Its topography

is the warrant for, and the explanation of, its high sanitary

rating.

These are but a few of the facts and salient characteristics

of a section of Arkansas that is, I believe, the rarest combination

of beautiful scenery, good weather and certain utility, in the

United States. I am told that there are other portions of the

state that equal if they do not surpass the four counties which

I have briefly mentioned in this writing. I believe it, though

I can't prove it. I know that the statements I have made seem

tame and trite in print after a short visit to the territory itself.

But out of it all I would like to convey some measure of the impression

made upon an experienced traveler, by the uniquely gentle beauty

of its contour, the caressing tenderness of its sky and air, the

alluring commingling of grandeur with simplicity, of freedom and

domesticity that distinguishes this portion of Arkansas from any

other section of the United States.

Frisco System | Stories Page

| Contents Page

|