FACTS ABOUT INDIAN TERRITORY

BY THOMAS F. MILLARD.

Probably more people now have their eyes turned expectantly

toward the Indian Territory, in anticipation of a settlement within

its boundaries, than to any other part of the world. For many

years this region has seemed to possess extraordinary attractions

to the home-seeker. This widespread sentiment had its beginning

soon after the removal of the five civilized tribes from their

lands east of the Mississippi, and has propagated with truly remarkable

fecundity ever since. The average mortal has only to be debarred

from anywhere, to at once feel his curiosity and desire stimulated.

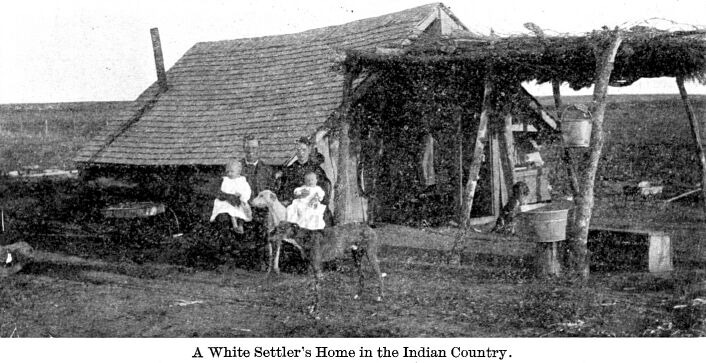

Scarcely had the Indians settled on their new possessions, than

white intruders, tempted by the fertility of the lands, invaded

the Territory, and here they have remained, notwithstanding all

efforts to eject them.

The settlement

of the Territory in spite of steady opposition, both from the

Indian governments within and the United States government without,

presents a curious anomaly in the development of a country, and

one that may well puzzle the student of such evolution. It must

truly be an unusual attraction that will induce 350,000 intelligent

people to move into a country where they are expressly told they

are not wanted, where they can own no real property, where to

remain means to sacrifice all political rights and absolute exclusion

from participation in affairs of either local or national government,

and where they must live under a constant threat of eviction.

Yet all this has happened. And the reason is not hard to discover.

To say that under such circumstances, the charms of the Territory

have apparently outweighed those of other sections of our broad

domain, is to pay the natural resources of the country a compliment

which would be difficult to parallel. The settlement

of the Territory in spite of steady opposition, both from the

Indian governments within and the United States government without,

presents a curious anomaly in the development of a country, and

one that may well puzzle the student of such evolution. It must

truly be an unusual attraction that will induce 350,000 intelligent

people to move into a country where they are expressly told they

are not wanted, where they can own no real property, where to

remain means to sacrifice all political rights and absolute exclusion

from participation in affairs of either local or national government,

and where they must live under a constant threat of eviction.

Yet all this has happened. And the reason is not hard to discover.

To say that under such circumstances, the charms of the Territory

have apparently outweighed those of other sections of our broad

domain, is to pay the natural resources of the country a compliment

which would be difficult to parallel.

Is this compliment to the Territory deserved? Well, a fact

is not easy to get around. The great states of Missouri, Kansas,

Texas and Arkansas surround the region originally set aside in

perpetuity for the Indians to live upon and enjoy the fruits thereof.

These states are not lacking in attractions to settlers. Their

resources may properly be termed extraordinary, since they have

sufficed, in the half century they have been included within the

confines of civilization, to attract and hold a population of

approximately eight millions, and there is ample room for twice

as many more. In those states residents have all the advantages

that modern civilization is able to confer. In many of these advantages

the Territory, owing to its peculiar situation, has been deficient.

Yet it has drawn, or, to speak correctly, been unable to exclude,

a population now exceeding, with the tribal citizenship, 400,000,

and thousands of others but await a betterment of conditions,

say rather a removal of the ban—to join the constantly swelling

tide of immigration. Within the period mentioned, a considerable

segment of the Indian Territory has been alienated, by purchase,

and thrown open to settlement. It detracts no whit from the marvelous

achievement that is the story of Oklahoma, to say that, notwithstanding

comparative disadvantages, the Territory now stands nearly even

with her in material development and population. Oklahoma has

thrown open her doors, and the response of energetic upbuilders

has carried her almost within a decade to the verge of statehood.

With doors that must be forced by those seeking admission, the

Territory has nevertheless kept pace with the vigorous stride

of her friendly rival. The fundamental vitality back of this accomplishment

must be indeed remarkable, even in a land of all on this earth

the most favored by nature.

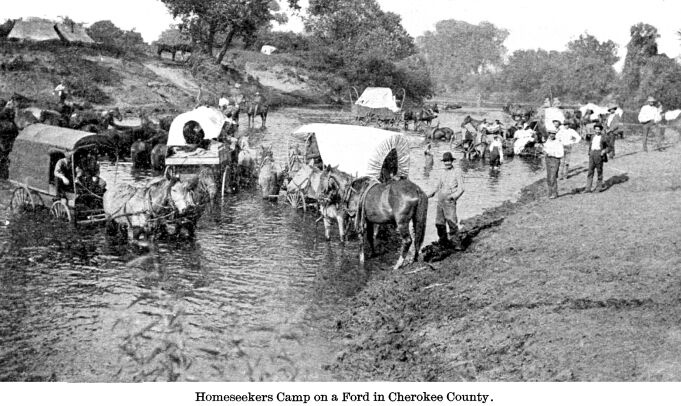

The reason for the present concentration of the interest of

homeseekers upon this country is to be found in the fact that

in the near future the adverse conditions that have operated in

the Territory are to be amelioriated. The ban is to be removed.

Settlers will no longer have the door slammed in their faces,

or, when once inside, be in perpetual fear of the bouncer. They

may come, and welcome. The lands of the Indians are to be allotted,

and once that is done a large percentage will be available for

occupation. And in view of this prospect, thousands of prospective

immigrants are anxious to ascertain the terms under which the

lands may be obtained. The present territorial possessions of

the five civilized nations comprise approximately 20,000,000 acres.

These lands, which have been held in common, are now to be distributed.

Each Indian citizen to receive a share. Deeds will be issued,

and, under certain restrictions and reservations, the lands will

be thrown open to occupation and tillage under terms that will

afford a reasonable security to the occupant. Owing to the fact

that conditions vary in each of the five nations, separate allotment

treaties were necessary, but the system and spirit of all the

treaties is practically the same. The general theory of the treaties

is to give each tribal citizen his or her fair share of the tribal

estate, and in order to accomplish this the government decided

that it was necessary to classify and appraise the land, according

to their character and value. In all the treaties it was deemed

prudent, for the protection of a people who had not been accustomed

to hold land in severalty, and who were consequently presumed

to be unacquainted with its values, to make a certain homestead

inalienable for at least a generation, and to throw safeguards

around the remainder during a brief period. It becomes important,

therefore, for anyone desiring to settle in the territory upon

any of the tribal lands to be informed fully as to the terms and

conditions imposed by the treaties. While, as I have said, the

treaties differ somewhat in minor details, their general principles

are the same, and an examination of the principal provisions of

one will give an insight into the workings of the others. Let

us, then, take a cursory glance at the terms of the treaty between

the United States government and the Cherokee Nation providing

for the allotment of the national lands.

On a basis of a pro rata division, each Cherokee citizen is

entitled to approximately 110 acres of land, but the method of

equalization adopted by the Dawes Commission will cause a great

variance in the allotments. A citizen who selects comparatively

valuable land, according to the appraisement, will naturally receive

much less than one whose selection embraces land that is comparatively

inferior. It thus happens that allotments in the Cherokee Nation

will probably vary from 80 to 640 acres, according to location.

Improvements are not taken into consideration in the appraisement,

for they go to the credit of the man who made them, and their

value is considered as apart from the natural value of the land.

In all cases, each citizen is given a prior opportunity to claim

the place where he has lived, and which he has probably improved.

When a citizen makes his selection he is required to designate

a homestead equal to 40 acres of the average land in the nation,

and under the provisions of the treaty he cannot alienate this

homestead in any way for 21 years after he secures his deed. Within

this period, this homestead cannot be encumbered, or taken or

seized for debt or any other obligation. All other lands in excess

of the homestead may be alienated at any time after five years,

and valid titles given. It should be borne in mind that, under

no circumstances, as the law is at present, can valid titles be

secured to lands within the Territory until five years after they

are allotted. But the lands may be leased just a soon as the allotment

is made. This section of the treaty, which has now been enacted

into law by Congress, reads as follows:

"Cherokee citizens may rent their allotments

when selected, for a term not to exceed one year for grazing purposes

only, and for a period not to exceed five years for agricultural

purposes, but without any stipulation or obligation to renew the

same; but leases for a longer period than one year for grazing

purposes and for a period longer than five years for agricultural

purposes and for mineral purposes may also be made with the approval

of the Secretary of the Interior, and not otherwise. Any agreement

or lease of any kind or character violative of this section shall

be absolutely void and not susceptible of ratification in any

manner and no rule of estoppel shall ever prevent the assertion

of its invalidity. Cattle grazed upon leased allotments shall

not be liable to any tribal tax, but when cattle are introduced

into the Cherokee Nation and grazed on lands not selected as allotments

by citizens the Secretary of the Interior shall collect from the

owners thereof a reasonable grazing tax for the benefit of the

tribe."

It will be noticed that short leases may be made without the

consent of the Secretary of the Interior, but long leases must

be approved at Washington. No agreement entered into by a Cherokee

citizen prior to the expiration of the time limit to sell his

land as soon as it shall be alienable will be valid. It will be

easily understood that the reason for these restrictions is to

prevent the Indians from selling the land before they have an

idea of its value. However, one great difficulty has been removed.

It will be possible to secure valid leases, for a limited period

without interference from Washington, and an unlimited period

with the consent of the Secretary of the Interior, and under these

leases the lands can be cultivated with as much security of possession

as in any of the states. This is a long step in advance, and an

immense immigration to occupy the millions of acres that have

never felt the plow is sure to come.

For about eight years, now, the Commission to the Five Civilized

Tribes, popularly known as the Dawes Commission, has been preparing

the way to allotment, with the result that the work is nearly

done. The land in the Seminole Nation has been allotted, that

in the Creek Nation is nearing completion, while in the Cherokee,

Choctaw and Chickasaw nations it is rapidly progressing. While

it is at present impossible to fix a date when this tremendous

and difficult labor will be finished, it now seems probable that

another year will suffice. The Secretary of the Interior has been

quoted as saying that the Territory will be thrown open to settlement

within two years, and he knows if anyone does. He probably means

that all deeds will be issued by that time, and all disputed claims

settled. From the time that is done, valid leases can be secured.

One hears in the Territory a great deal of more or less bitter

criticism of the delay of the government in perfecting allotment.

This criticism comes from all classes, but it seems to be founded

rather on impatience than upon dereliction of the Interior Department.

Accusations that every possible means to delay the issuance of

deeds are employed by those in authority are freely bandied about.

It is difficult to determine the justice or injustice of these

charges, but to me they do not seem to be well founded. Perhaps

the most that can be said about the attitude of the government

is that it shows no disposition to accelerate matters beyond the

normal rate of progress. This normal headway will finish the job

in a comparatively short time now.

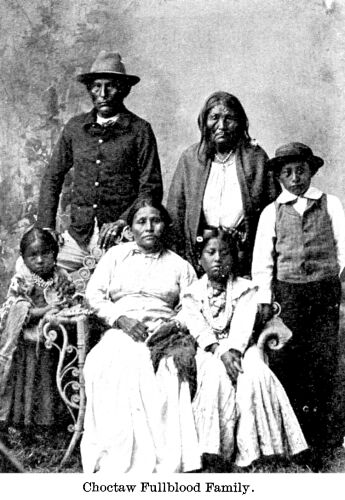

While the situation respecting land tenure in the Territory

stands in this shape just now, it is highly probable that by the

time the allotment is finished some supplemental legislation will

be enacted, by which the time limits within which titles may not

be conveyed will be modified, or in many cases done away with

altogether. The reason for these limitations has already been

explained. The portion of Indian citizens who are even theoretically

assumed to need a temporary guardian does not exceed 20,000, out

of a total tribal citizenship of about 85,000. This portion consists

chiefly of full-bloods, who have been backward in learning the

ways of the white man. It may be that it will be to the advantage

of this class of Indian, to prevent him from selling his homestead

for a generation, but such a theory can scarcely be assumed to

apply to the practically "white Indians," of mixed blood

who constitute fully three-fourths of the tribal population. These

people are as capable of managing their own business now as they

ever will be, and they deeply resent being tied up as wards in

chancery. They want to be able to do as they please with their

property, and no one who is at all familiar with their situation

will think of denying the justice of their position. It would

be just as reasonable for the government to prevent a Pennsylvania

or Illinois farmer from selling his land on the theory that he

was not capable of managing his own business. I assume that the

Secretary of the Interior and Congress fully realize this, and

will consent to a modification of some of the provisions of the

treaties. The only difficulty in the way of supplementary legislation

is how to determine who is and who is not entitled to exemption.

Two methods have been suggested: The first, that the Territorial

courts be given jurisdiction to determine such competency, on

presentation of evidence; second, that this power be given to

the Secretary of the Interior. Either plan would answer, although

public opinion in the Territory is overwhelmingly in favor of

delegating this office to the courts, as being the most satisfactory

and expedient. At any rate, some legislation of this nature is

looked for, and if it is enacted fully three-fourths of the land

in the Territory will be at once placed on the same footing as

land in any of the state.

Conditions in

the towns are entirely different, being regulated by separate

provisions of the treaties. To put the matter in a nutshell, all

townsites are to be located—in fact, all in existence have

already been located—by the Dawes Commission. The town lots

are to be allotted to whoever can establish a valid claim before

the townsite commissions, and all lots that are unclaimed are

to be sold at auction, the money to be turned into the tribal

treasuries. In many of the towns the allotments have already been

made, and some of the sales held. A great majority of the principal

towns, however, are yet to be allotted, and persons who desire

to secure good property for business or manufacturing purposes

in the towns should take note of the public sales, which will

all be duly advertised. Whether bought at one of these sales,

or from the holder of the deed after all claims have been settled,

titles on town property will be entirely free from any restrictions

from the beginning. While the practical benefit to the Indians

of the equalization undertaken by the Dawes Commission, viewed

broadly, may well be doubted, it affords a remarkably good means

of determining the character of the 20,000,000 acres of tribal

lands, that comparatively unscathed empire toward which so many

eager eyes are now turned. A general impression seems to prevail

that the Indian Territory is almost entirely prairie. As a matter

of fact, about 65 per cent of the present area is timbered land.

The general character of the landscape does not materially differ

from large portions of Indiana, Illinois or Missouri. While there

are, particularly in the northern part, wide stretches of prairie,

the river bottoms and almost the whole of the Choctaw and Chickasaw

nations are liberally supplied with a fine growth of timber. The

general topography is an undulating upland, plentifully watered

by the great streams of the Arkansas, Canadian and Red Rivers,

and their numerous tributaries. The river bottoms, of which there

are millions of acres, are equal in richness to any in the world,

while the prairies and upland are of almost equal fertility. Conditions in

the towns are entirely different, being regulated by separate

provisions of the treaties. To put the matter in a nutshell, all

townsites are to be located—in fact, all in existence have

already been located—by the Dawes Commission. The town lots

are to be allotted to whoever can establish a valid claim before

the townsite commissions, and all lots that are unclaimed are

to be sold at auction, the money to be turned into the tribal

treasuries. In many of the towns the allotments have already been

made, and some of the sales held. A great majority of the principal

towns, however, are yet to be allotted, and persons who desire

to secure good property for business or manufacturing purposes

in the towns should take note of the public sales, which will

all be duly advertised. Whether bought at one of these sales,

or from the holder of the deed after all claims have been settled,

titles on town property will be entirely free from any restrictions

from the beginning. While the practical benefit to the Indians

of the equalization undertaken by the Dawes Commission, viewed

broadly, may well be doubted, it affords a remarkably good means

of determining the character of the 20,000,000 acres of tribal

lands, that comparatively unscathed empire toward which so many

eager eyes are now turned. A general impression seems to prevail

that the Indian Territory is almost entirely prairie. As a matter

of fact, about 65 per cent of the present area is timbered land.

The general character of the landscape does not materially differ

from large portions of Indiana, Illinois or Missouri. While there

are, particularly in the northern part, wide stretches of prairie,

the river bottoms and almost the whole of the Choctaw and Chickasaw

nations are liberally supplied with a fine growth of timber. The

general topography is an undulating upland, plentifully watered

by the great streams of the Arkansas, Canadian and Red Rivers,

and their numerous tributaries. The river bottoms, of which there

are millions of acres, are equal in richness to any in the world,

while the prairies and upland are of almost equal fertility.

Notwithstanding that less than one-sixth of the land is now

being cultivated, the output of agricultural products is so great

that the railroads are pushed to handle the surplus. The demand

for cars at all shipping points is so great that shippers are

compelled to file applications weeks in advance, and then await

their turn. One day recently that I spent at Vinita, in the Cherokee

Nation, 700 wagon loads of corn were brought to town, and the

daily average at this season is from 200 to 300 loads. It is not

uncommon for wagons to stand all night at the mills waiting for

a chance to unload. The shipments of hay from this same place

are also astonishing. Stations where one would scarcely expect

trains to stop, so few are the external evidences of population,

to say nothing of life, send out daily several car loads of produce.

In the more southern portion of the territory, cars to handle

the cotton crop can be secured only with difficulty, although

all the railroads in the Territory are making every effort to

meet the demands of traffic. Think of this, and the earth hardly

scratched. One would expect, as is the case in most new countries,

that the imports would greatly exceed the exports. Already the

reverse is true of the Territory. The "empties," as

railroad men call unloaded cars, are hauled into, not away from,

the Territory. This curious reversal of the ordinary course of

traffic is a surprise, and somewhat of a puzzle, to railroad operators,

and they are already wondering what they will do when the country

is settled. However, railroad construction is being pushed everywhere

with extraordinary activity, and there is no doubt that the problem

will be solved.

As would naturally follow, the compliment to this agricultural

production is to be found in the obvious commercial activity that

everywhere pervades the towns. In this connection, a somewhat

curious condition is apparent. It is estimated that four-fifths

of the present population of the Territory resides in the towns.

This seeming disproportion, in a country where manufactures are

as yet a minor element in industry, would indicate that a majority

of the people are "living off each other," as a resident

put it. Yet there is no evidence of the stagnation that would

be the inevitable result if that situation really existed. The

capital that is daily coming in with the tide of immigration is

probably what preserves the balance now, but bankers and those

in touch with the business situation profess to feel not the slightest

uneasiness as to the ultimate outcome. They confidently predict

that development will keep pace with the immigration, the concentration

of the population in the towns being more apparent than real,

and due to the fact that the country is passing through a critical

formative period, and that production will more than equalize

matters before any strain is felt. Observing conditions on the

spot, I am inclined to accept this explanation as a just one.

There are not apparent, either on the surface or in the forthcoming

sequence of events, any indications of a reaction. The present

rate of development in the Territory is sound, for the land is

here to support it.

For purposes of appraisement, the Dawes Commission has classified

all the lands in the Territory according to schedules. The land

in the Seminole Nation, which is not extensive, was divided into

only three grades, and allotted on that basis. However, in the

other four nations the land was of such extent and diversity of

character that more minute divisions were deemed necessary. The

remainder of the Territory was divided into two parts, one consisting

of the Cherokee and Creek Nations, and the other of the Choctaw

and Chickasaw nations, and a schedule for each devised to fit

the land as near as possible. I believe these schedules will be

of value to persons anticipating a location in the Territory,

especially if they intend to cultivate a farm, and so I will insert

them.

Following is the classification schedule for the Creek and

Cherokee nations:

Class 1. Natural open bottom land.

Class 2. Best black prairie land.

Class 3 (a). Bottom land covered with timber and thickets.

Class 3 (b). Best prairie land other than black.

Class 4 (a). Bottom land subject to overflow.

Class 4 (b). Prairie land, smooth and tillable.

Class 5 (a)- Rough land free from rocks.

Class 5 (b). Rolling land free from rocks.

Class 6 (a). Rocky prairie land.

Class 6 (b). Sandy prairie land.

Class 7 (a). Alkali prairie land.

Class 7 (b). Hilly and rocky land.

Class 8 (a). Swamp land.

Class 8 (b). Mountain pasture land.

Class 9 (a). Mountain land, sandy loam.

Class 9 (b). Mountain land, silicious.

Class 10 (a). Rough and rocky mountain land.

Class 10 (b). Flint hills.

The following table shows the lands of the Creek nation,

as classified under the above schedule. Fractions of acres are

omitted.

|

|

Acres |

|

Class 1 |

12,410 |

|

Class 2 |

1,739 |

|

Class 3 (a) |

194,596 |

|

Class 3 (b) |

124,400 |

|

Class 4 (a) |

112,385 |

|

Class 4 (b) |

571,803 |

|

Class 5(a) |

298,507 |

|

Class 5 (b) |

770,756 |

|

Class 6 (a) |

202,744 |

|

Class 6 (b) |

46,783 |

|

Class 7 (a) |

31,135 |

|

Class 7 (b) |

512,282 |

|

Class 8 (a) |

25,469 |

|

Class 8 (b) |

91,310 |

|

Class 9 (a) |

15,477 |

|

Class 9 (b) |

1,464 |

|

Class 10 (a) |

59,546 |

|

TOTAL |

3,072,813 |

The following table gives the lands of the Cherokee Nation,

as classified under the schedule, fractions omitted.

|

|

Acres |

|

Class 1 |

11,646 |

|

Class 2 |

1,623 |

|

Class 3 (a) |

143,836 |

|

Class 3 (b) |

231,900 |

|

Class 4 (a) |

213,903 |

|

Class 4 (b) |

899,207 |

|

Class 5(a) |

322,555 |

|

Class 5 (b) |

634,948 |

|

Class 6 (a) |

414,899 |

|

Class 6 (b) |

5,673 |

|

Class 7 (a) |

7,700 |

|

Class 7 (b) |

614,362 |

|

Class 8 (a) |

15,540 |

|

Class 8 (b) |

159,394 |

|

Class 9 (a) |

12,062 |

|

Class 9 (b) |

41,142 |

|

Class 10 (a) |

220,341 |

|

Class 10 (b) |

469,330 |

|

TOTAL |

4,420,070 |

Following is the classification schedule for the Choctaw

and Chickasaw nations:

Class 1. Natural open bottom land.

Class 2 (a). Cleared bottom land.

Class 2 (b). Best black prairie land.

Class 3. Bottom land covered with timber and thickets. (If the

timber is of commercial value, it will be appraised separately.)

Class 4 (a). Best prairie land, other than black.

Class 4 (b). Bottom land subject to overflow.

Class 5 (a). Prairie land, smooth and tillable.

Class 5 (b). Swamp land easily drainable.

Class 6 (a). Rough prairie land.

Class 6 (b). Upland with hard timber. (If the timber is of commercial

value, it will be appraised separately.)

Class 7 (a). Rocky prairie land.

Class 7 (b). Swamp land not easily drainable.

Class 8 (a). Alkali prairie land.

Class 8 (b). Hilly and rocky land.

Class 8 (c). Swamp land not profitably drainable.

Class 8 (d). Mountain pasture land.

Class 9 (a). Sandy land with pine timber. (If the timber is of

commercial value, it will be appraised separately.)

Class 9 (b). Mountain land with pine timber. (If the timber is

of commercial value, it will be appraised separately.)

Class 10. Rough mountain land.

The following table shows the lands of the Choctaw nation,

as classified under the above schedule, fractions of acres omitted.

|

|

Acres |

|

Class 1 |

1,065 |

|

Class 2 (a) |

3,399 |

|

Class 2 (b) |

35,235 |

|

Class 3 |

286,190 |

|

Class 4 (a) |

89,764 |

|

Class 4 (b) |

281,234 |

|

Class 5(a) |

526,187 |

|

Class 5 (b) |

21,281 |

|

Class 6 (a) |

129,020 |

|

Class 6 (b) |

2,134,427 |

|

Class 7 (a) |

145,313 |

|

Class 7 (b) |

37,787 |

|

Class 8 (a) |

19,125 |

|

Class 8 (b) |

1,390,480 |

|

Class 8 (c) |

14,665 |

|

Class 8 (d) |

289,276 |

|

Class 9 (a) |

265,594 |

|

Class 9 (b) |

765,895 |

|

Class 10 |

514,296 |

|

TOTAL |

6,950,043 |

The following table gives the lands of the Chickasaw nation,

as classified under the schedule, fractions omitted.

|

|

Acres |

|

Class 1 |

83,176 |

|

Class 2 (a) |

15,014 |

|

Class 2 (b) |

29,974 |

|

Class 3 |

145,458 |

|

Class 4 (a) |

173,026 |

|

Class 4 (b) |

182,819 |

|

Class 5(a) |

1,505,116 |

|

Class 5 (b) |

12,381 |

|

Class 6 (a) |

223,800 |

|

Class 6 (b) |

1,748,513 |

|

Class 7 (a) |

191,995 |

|

Class 7 (b) |

3,673 |

|

Class 8 (a) |

22,285 |

|

Class 8 (b) |

307,962 |

|

Class 8 (c) |

2,214 |

|

Class 8 (d) |

53,181 |

|

Class 9 (a) |

0 |

|

Class 9 (b) |

0 |

|

Class 10 |

2,512 |

|

TOTAL |

4,703,108 |

From this classification it appears that about four-fifths

of the total area of the Territory is arable, and most of the

remainder is valuable for other purposes. A large part of the

land not classed as arable is designated as swamp land, susceptible

to drainage, so there is no doubt that in time it will be reclaimed

and added to the producing part of the Territory. In fact, it

is highly probable that this land may become exceedingly valuable,

for it is peculiarly adapted for the culture of rice, which industry

is being the means of reclaiming the swamp lands of Louisiana

and eastern Texas. It is said that rice growers already have their

eyes on this country, with a view to developing it as soon as

they can secure possession under valid leases. Much of the land

is very valuable for its timber and for other natural resources,

such as coal and oil deposits, which are to be found almost everywhere

in the Territory, and the great shale deposits at Sapulpa, which

are already the foundation upon which great manufacturing enterprises

are being predicated. The whole of the Territory lies well within

the rain belt, and the impression that has got abroad that this

is an arid country is entirely erroneous. Severe droughts are

rare, even more so than in the neighboring states of Missouri,

Kansas and Texas. The notion that the country has a deficient

rainfall probably arises out of the false impression that it is

poorly timbered, which I have already shown to be incorrect. The

tables given are the result of the work of skilled observers,

who covered every mile of the Territory and examined every acre

of the land, and may be depended upon to delineate the character

of the lands with reasonable accuracy. As to climate, it is very

similar to that of Tennessee, the winters being mild, with very

little snowfall, and the summers of moderate heat.

As yet the land has not been appraised; that is, no value in

dollars and cents has been placed upon the various grades, except

in the small Seminole country. It will not be long, however, before

this appraisement is made, and when it is, it will enable one

to get a very fair idea of the value of the land, if one fully

understands the system under which the valuations are determined.

The rules governing the classification of the lands give a clue

to the method employed. These rules follow:

1. Lands shall be valued in the appraisement as if in their

original condition, excluding improvements.

2. Appraisers will grade and appraise lands without regard

to their location and proximity to market.

3. Land will be graded and appraised by quarter sections except

in cases where a part of a quarter is of a. different grade from

the rest. In such cases of the quarter sections will be graded

and appraised in smaller parcels, but no parcel to be less than

40 acres.

4. If timber is of commercial value, the quantity will be carefully

estimated and the variety stated, and it will be valued separately;

and if not generally distributed over the tracts, its location

will be given.

5. Upon completion of this work the values will be adjusted

by the Commission to the Five Civilized Tribes on the basis of

the values fixed for each class and the location of the lands

and their proximity to market.

Given the rules governing the classification, the classification

tables, the classification schedules, and the definite appraisement,

all of which, except the appraisement, are here reproduced, and

a prospective purchaser of lands in the Territory will be able

to determine with tolerable accuracy the character and value of

a piece of land in any locality.

Of course, he must first learn how the land he fancies is classified,

and that can be done by referring to the completed allotment lists

of the Dawes Commission, whenever those lists are completed. Moreover,

by a judicious study of the tables, one may without difficulty

select approximately the kind of land one desires. Do you desire

natural open bottom land? There is a certain stated amount to

be had, and a little inquiry will reveal where it is located.

Do you prefer black prairie land? You will find it classified

and marked out for your inspection. Are you looking for heavily

timbered land on which to operate a saw mill, or mountain pasture

land on which to locate a goat ranch? Both are available. In fact,

you can pay your money and take your choice. And, bear in mind,

this estimate of the character and value of the lands is not that

of the proprietor, but that of impartial experts employed by the

United States government. It is to be presumed that appraisements

will not represent actual market values, but will be within the

usual limitation imposed by similar circumstances. It is probable

that the appraisement will be comparative rather than specific,

for its only object is to afford a basis of comparison on which

to equalize the allotments, but it will nevertheless give a considerable

insight into actual values as conditions are today, with the exceptions

as to improvements and locality noted by the rules. Those are

advantages to be weighed by prospective purchasers, and will fluctuate

in value according to individual desires.

Within the year just past, thousands of persons have taken

advantage of favorable opportunities afforded by the railroads

entering the Territory to inspect the country. I have encountered

these "prospectors" everywhere. Few, indeed, are disappointed

with what they see, but I find that many had before coming an

erroneous impression as to the conditions under which the Territory

is soon to be thrown open to settlement. Many thought that, as

soon as the Dawes Commission has finished its work, the lands

may be purchased outright. Some, when they learn the facts, feel

a sense of disappointment and are somewhat averse to locating

upon land they cannot, at least for a time, own. That this consideration

will cause many who had entertained a project to remove to the

Territory to change their mind, or defer moving in the matter,

is certain. In a country where no man is so poor but he may, if

he really wishes to own some land, many are disinclined to settle

upon ground to which they do not hold a title. However, unless

one is swayed chiefly by sentimental considerations, such objections

must fall to the ground in this instance. Owing to the fact that

the lands of the small tribes that occupy the Quapah Agency, in

the northeast part of the Territory, have been allotted for over

ten years under almost exactly similar provisions as will obtain

in the Five Nations, we may observe how the system operates when

put into practice. Nearly all the land in the Quapah Agency is

cultivated by white persons under leases, and the arrangement

has worked with complete satisfaction to all parties concerned.

Take the Five Nations. Here practically all the land that is

in cultivation has been tilled by white men, the interlopers whose

presence gave perpetual offense. These lands were cultivated under

conditions where not even valid leases could be obtained, where

all improvements became the property of the tribes, and where

the tenants were in constant fear of eviction which they would

have been powerless to resist. Yet the lands found men willing

to cultivate them. What more need be said? There is no scarcity

of land as yet in the United States. There is land in plenty.

But some is more desirable than others. The fact that white amen

cultivated the Indian lands under insecure tenure, or no tenure

at all, is absolute proof that they found it profitable to do

so. If they found it profitable under no tenure, is it not reasonable

to assume that under secure leaseholds, with a prospect of eventual

possession, it will also be profitable? Moreover, conditions are

vastly more favorable in other respects. Formerly this region

was isolated from the world's markets. Now it is rapidly becoming

a network of railway lines. Within five years a railroad map of

the Territory will look like a spider's web. If the present rate

of construction continues, and there is no doubt that it will.

Five great systems now reach, the Territory, and all have the

building fever. The railroads are getting into shape to handle

the traffic that will result when the additional million, expected

to arrive within the next ten years, gets on the ground and to

work.

So the "prospector" who comes to the Territory now

will have no just cause to regret his journey. He is a seeker

for opportunity, and opportunity is here. If he be a farmer looking

for land, he may find himself just a little ahead of time, but

to be ahead of time is generally estimated an advantage. The man

who is ahead of time is infinitely better off than the man who

is behind time. But is the "prospector" who comes to

the Territory now ahead of time? I should say, decidedly not.

A man does not, or should not, change his home without good cause.

He must see, or think he sees, a fair chance to better his condition.

If he is wise, he will "prospect" a little before taking

the plunge; and if he expects his "prospecting" trip

to result in anything, he must certainly not be behind time, or

he will find that others have seized the opportunity he sought,

while it was yet newborn from the womb of progress.

In a short time, now, this fertile region will open its arms

to embrace the men whose destiny is to convert its teeming resources

to the uses of mankind. It is, indeed, fortunate that this brief

interim will intervene. It means that homeseekers will have ample

opportunity to look over the ground, decide upon a location, and

prepare for removal. It means that the new territory will not

start handicapped by the unsettled conditions that always follow

a "rush." Its "boom" will be more gradual,

but will lose no impetus on that account. The foundations are

well laid, the results certain. I have had occasion, during the

past few years, to traverse a large part of the earth's surface,

and if I were asked today to name the locality most likely in

my opinion, to enjoy during the forthcoming decade the most substantial

development, I should, without hesitation, reply:

"The Indian Territory."

Frisco System | Stories Page

| Contents Page

|