|

THE GREAT LEAD AND ZINC

FIELDS.

BY THOS. MILLARD.

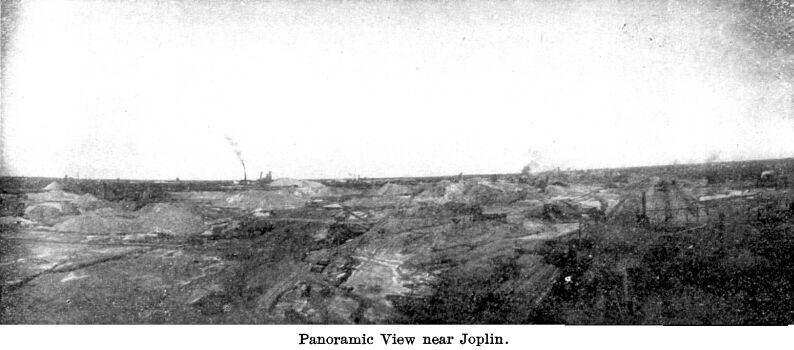

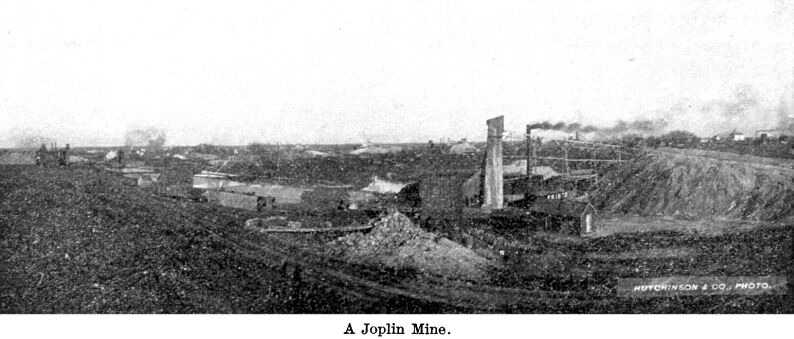

What the Witwatersrand is to the world as a producer of gold,

the great Joplin lead and zinc district is as a producer of those

humbler but even more necessary metals. Both camps, if settled

communities bubbling with life and business activity may be so

termed, are at the head of their class, and they have many points

of similarity, even to the more than superficial observer. Entering

the Joplin district from the eastward, by way of the Frisco System,

I was at once struck with the outward resemblance. In. fact, it

would have required but little exercise of the imagination to

have fancied myself looking from a car window out upon the seething

environs of Johannesburg. The landscape is almost identical. There

are the wilderness of smoking funnels standing against the sky

like a limbless forest, the vast slate-colored dumps of tailings,

the labyrinth of car tracks, puffing switch engines and swinging

derricks; the succession of "camps," some approaching

the dignity of cities, where on every side prospect shafts and

mines dispute the surface of the earth with pretentious buildings;

the suggestion of a community which at one moment represents all

steps along the path of progress; and, pervading it all, the indelible

impression of restless, untamable energy.

It is now more than 50 years since lead was discovered in southwest

Missouri, near the Kansas border. The first attempts to mine were

made near the present site of Joplin. For many years the business

was conducted in the most primitive fashion, and under difficulties

of almost overpowering nature. The town of Booneville, on the

Missouri river, whence the ore could be shipped via water to market,

was the nearest available point located on an avenue of commerce,

and it had to be hauled there in wagons. However, in time these

adverse conditions were ameliorated, and when the St. Louis &

San Francisco railroad penetrated the southwest, capital soon

saw its opportunity. From the date of acquirement of railroad

facilities, the real development of the mining district began.

Since then its story has been one of comparatively uninterrupted

progress. The district now supports directly and indirectly, some

200,000 people. From a few acres, it has spread over the greater

part of Jasper county, Mo., and across the line into Kansas, covering

some 600 square miles. It includes the towns of Joplin, Webb City,

Carthage, Carterville, Oronogo, Central City, Duenweg, Spring

City, Neck City and Chitwood, in Missouri, and Galena, and a number

of small camps in Kansas. Properly the district should include

the great coal district lying around Pittsburg, Kansas, for, owing

to the fact that it is cheaper to transport lead and zinc than

coal, nearly all the smelters have located near the coal mines.

Thus it is no exaggeration to say that much of the industry lying

within the borders of the Kansas coal district derives its support

from the lead and zinc mines.

Especially in recent years, the growth of the district has

been remarkable. Zinc was not discovered until 1874, when a chemical

analysis of some peculiar looking stuff that had been habitually

cast upon the waste dumps of the lead mines revealed it to be

zinc ore of the highest grade. It was not long before lead mining

took a secondary place, as zinc mines were rapidly opened. Reports

of the new discovery brought thousands of people into the district,

and prospecting began to be extensively carried on. Between 1889

and 1899 the annual output of the district rose from less than

$3,000,000 to nearly $11,000,000. Of this, the zinc production

furnished probably, on the average, nine-tenths of the value.

Since 1899 the output has fallen off slightly in total value,

but this has not been due to a decrease in production. The unusual

value of the 1899 product was due to extraordinary prices which

were more than double those of the previous year, and about 25

per cent greater than at the present time. As few persons anticipated

that the extraordinary prices of 1899 would be maintained the

subsequent depression gave the industry no permanent set-back,

and the mining community is very well satisfied with prevailing

conditions. Present prices are more than 100 per cent greater

than prices five years ago, and the general tendency of the market

seems to be upward, owing to the constant opening of new markets

and uses for zinc products.

In 1898 what was considered a tendency on the part of the zinc

smelters to keep down the price of ore, resulted in the organization

of the Zinc Miners' Association, with headquarters at Joplin.

Conditions at that time were such as to enable the smelters to

practically regulate prices, which they did to their own advantage

in some instances, and to the disadvantage of the miners. After

a season, during which the Miners' Association exported considerable

quantities of ore to Belgium at a loss, improved relations with

the smelters followed, and relations between the producing and

purchasing branches of the industry are now more satisfactory.

The district is frequently referred to as "the poor man's

camp," and it seems that the title is not undeserved. In

a great majority of mining districts poor men have practically

no chance to operate after the field has once been thoroughly

"proved up." Once the development stage is past, the

poor man finds himself unable to go ahead, and is usually compelled

to sell out to persons who can command capital. For years, now,

in the Johannesburg field, all claims have been in the hands of

a capitalistic combination, composed of multi-millionaires, which,

until it is ready to operate them, lets them lie untouched, to

the exclusion of any who may desire to work them. Peculiar conditions

in the Joplin district render it difficult—some persons say

impossible—for any combination that might be formed to control

operations in the lead and zinc fields.

"Any company that tries it," said a prominent Joplin

capitalist, who is thoroughly conversant with the situation, "will

go broke sooner or later, and it probably will be sooner."

Then he went on to explain.

One reason—and it is a good one—is that the field

is too large. It is difficult to conceive the organization of

a company with sufficient capital to purchase or control, at the

prices the owners hold it at, 600 square miles of land. Even if

the money could be raised for such a purpose, there is no possible

way by which dividends on the money invested could be paid. The

chances are, on the contrary, that an attempt to develop the field

would soon result in bankruptcy. While the entire district is

theoretically mineral bearing land, it is only in certain localities

that zinc or lead can—or has been—found in paying quantities.

People who have made a study of the field are confident that the

whole country is underlaid with both lead and zinc, in practically

unlimited quantities; but undoubtedly much, if not most of it,

lies at depths beyond present facilities. In time, there is no

doubt that we will mine successfully at great depths, but at present,

and for years to come, we will be compelled to pick our ground.

At present most of the ore being worked lies just beneath the

surface of the ground, and mining is rarely conducted at a greater

depth than 150 feet.

"The district was developed in the beginning, and is still

being developed by poor men. Conditions favor them, or rather,

give them opportunity. There is not a property owner within the

limits of the district but has a chance of leaving a lead or zinc

deposit under his farm or town lot. It generally happens that

these men either lack the means or are reluctant to take the financial

risk necessary to prospect for ore. Therefore, they are willing

to permit others to prospect on their land, in the hope that a

profitable discovery will be made. Here comes the opportunity

of the poor man. It, does not cost much to sink a prospect shaft,

and miners, probably more than any other class of men, are deeply

imbued with the speculative spirit. A number of miners, all of

them working in the mines for daily wage, will club together,

agreeing to pay each a certain sum daily or weekly, out of their

earnings, to prospect. They will lease a piece of ground, and

set a couple of men to work sinking a shaft. If they make a paying

strike, they sell out to an operator, this class being composed

of men of limited capital, who are able to work a prospect. If

nothing is struck, the project is abandoned, and the miners regard

their losses philosophically, taking another chance as soon as

they can afford it.

"By this method, the operating mines, and a certain percentage

of the wages of the district goes toward additional development.

Capital is not called upon to risk until it has something tangible

to operate upon. Then it takes hold. It is perfectly fair for

all parties. If capital at tempted to prospect the district, it

would fritter its substance away before the real business of ore

production began. This has been the experience of those who have

tried it, almost without exception. When I tell you that not over

five per cent of the known mineral bearing land has been prospected,

you will see that the poor man's opportunity has by no means passed

away in the district. There will be room for him for a long time

to come."

The method of conducting business in the district is unusual,

but from its practical working seems entirely satisfactory. Nearly

all the mines are operated under leasehold by the terms of which

a percentage of the output goes to the owner of the land, and

the remainder to the operator. Once a week the buyers for the

smelters visit each mine, and bid for the weekly product. These

buyers are experts in estimating the value of "jack"

as the concentrated ore is locally called, and by merely glancing

at a dump can tell almost its exact value. Every Saturday the

"jack" purchased during the week is paid for. However,

payment is not made to the mine operator, but to the owner of

the land, who takes out his percentage and gives the remainder

to the lessee. It frequently happens that after a tract of land

is leased by a certain party, he will divide it into small lots

and sublet them to small operators. This results in diversifying

the interests, and prevents too much power over the destinies

of the district from being concentrated.

Promptly at 5 o'clock every Saturday afternoon, the operators

pay their help, which constitutes the great working force of the

district; the weekly output of all the mines is about $200,000,

of which probably $50,000 goes into the hands of the miners. From

them it passes on into ordinary channels, and eventually the greater

part of it reaches the shops.

It is interesting to be in Joplin on a Saturday night. The

city, which is the commercial center of the district, has a population

of 30,000, but on a Saturday evening thousands of people who work

and reside in the other "camps" pour in to swell the

crowds that throng the streets and fill the shops to overflowing.

All the principal towns in the district are connected by electric

railways, which makes Joplin easy of access from all directions,

and from Saturday noon until long after midnight the trolley cars

can with difficulty handle the passengers. The banks remain open

until 11 o'clock and most of the business houses do not close

until midnight. The streets are so densely thronged that one can

only make way with the greatest difficulty.

Gambling places, saloons, and all places that afford amusement

are liberally patronized. Fortunately, the miners of the Joplin

district, while containing a small disorderly, or "tough"

element, are considered the best in the world. The toughs are

too much in the minority to seriously affect social conditions,

and while an occasional street brawl occurs, the crowds are surprisingly

well behaved. On the whole, it is a crowd of excellent appearance.

When a miner leaves his drift, he doffs his working garb, and

appears on the streets in the costume of a prosperous business

man. The superior character of the miners in this district is

due to the fact that they are principally drawn from the surrounding

country. They came off the farms and out of the villages of Missouri,

and their early training makes them good citizens. They are very

different from miners in other parts of the world. There are comparatively

no foreigners in the district, and labor troubles are almost unknown.

The reason for the absence of friction between the operators

and the men who work in the drifts and mills lies in the fact

that almost every miner has a personal interest in the future

of the district. I have already mentioned the system under which

the field is being developed. When half the miners in the district

are directly interested in some prospect or mine, anything like

a general strike is impossible. The men are not likely to strike

on themselves. There are no miners' unions, not that the men are

hostile to unions in general, but because they have not felt the

need of them. Another element that makes for harmony between miners

and operators is that both belong, generally speaking, in the

same social class. Frequently the same man is both a miner and

operator, and a great majority of the operators came out of the

mines. Bear in mind that an operator in the Joplin district must

not be confounded with the men who, from offices in New York city,

virtually control the destiny of thousands of miners in the great

coal fields. He is altogether another type. Usually he has not

much wealth, and depends on the working of a small piece of ground

for his living. He knows the miners intimately, and his point

of view is the same as theirs. In fact, to put the matter in a

nutshell, in the Joplin district the general policy is "live

and let live," and natural conditions seem destined to perpetuate

it. There is strong probability that during its existence the

great Missouri-Kansas lead and zinc field will always deserve

the title, "the poor man's camp.

Fortified against labor troubles, the bete noir of all other

mining centers, by a system that gives every man an equal chance,

the future of the Joplin district seems bright. In the opinion

of experts, the field has hardly been scratched. The ore that

lies near the surface is far from exhausted, and deep borings

have revealed large ore bodies at great depths. Of course, the

expense of mining increases as it goes down, but the introduction

of improved methods and machinery have so far about equalized

matters. Industries naturally associated with mining, and the

manufacture of zinc and lead products, have shown a disposition

to gather around the center of production. Seven large foundries

and shops, which turn out every kind of mining machinery, are

already located in the district, while immense plants which convert

the raw product of the mines into marketable form are to be seen

on every side. Nearly all the land in the district is extraordinarily

rich for agricultural purposes, and it is a common thing to see

land producing large crop, while vast quantities of ore are being

at the same time taken from underneath the surface. The field

has had a wonderful past, but its future promises to be still

more wonderful.

Frisco System | Stories Page

| Contents Page

|