|

CHAPTER II—BEGINNING OF RAILROAD CAREER; COURTSHIP

AND MARRIAGE

GOING to Atlanta I started on my railroad life as a brakeman

on the Western and Atlantic, known as the Georgia State Road.

The line was from Atlanta to Chattanooga and was one hundred and

thirty-eight miles in length. It took four days to make a round

trip on a freight train. We had a relay point about half way,

and when the sun set, we would "lie up" until next day,

as the engines were without headlights.

The pay I received was $20.00 per month, with board and lodging

while out on the road. The conductor carried a "meal book"

and kept the account of all his crew, receiving $50.00 per month

wages. Engineers were paid $2.50 per day, except passenger engineers

who got $3.00

I remained on this road until June, 1859, then secured a position

as baggage master on the Macon and Western, that ran from Atlanta

to Macon, a distance of one hundred and two miles.

While on this road, I fell in love with a girl in Atlanta,

and in order to have a longer "lay over" in that town,

I quit handling baggage, in October, and went to firing. My Atlanta

girl wanted me to marry her, but after thinking the matter over,

and considering that she was several years my senior, decided

that I didn't want to marry, so threw up my job in February, 1860,

and started out again.

I went this time to Huntsville, Alabama. Upon arriving there

I went to the Memphis and Charleston shop and asked for a job

of running an engine. The Master Mechanic was an Irishman, by

the name of Crawford. He usually got the name of "Uncle Jimmie,"

and was rather a queer fellow, who wore his hat on the back of

his head. When I applied for work he gave me a searching look,

and said: "Ye look mighty young to be an engineer."

He asked me where I came from, and when I replied that I was from

Georgia, he said he had had enough of Georgians. Just here a mutual

friend stepped up and said to Mr. Crawford: "If you hire

this man you will never regret it." He finally decided he

would give me a job of switching, and taking the engines in and

out of the roundhouse. In addition to these duties, I had to run

the engine that sawed the wood, as well as do various other things.

My work was satisfactory to "Uncle Jimmie," and he

kept me as long as he could. The friend that recommended me met

him a short time after I started in to work, and asked him how

he liked me. His reply was, that I was the best man that he had

ever met that came from the State of Georgia, and had never given

him any trouble. My friend was also from Georgia and reminded

"Uncle Jimmie" of the fact. "I gad," he said,

"I don't take anything back."

A little incident will show what a close observer our Master

Mechanic was. My arms were large and sinewy, and one day I had

my sleeves rolled up to my shoulders, busily engaged in cleaning

an engine, when "Uncle Jimmie" came along. He watched

me for awhile, then remarked to a man near him, " I gad,

look what arms! I would just as soon be struck by the Donnegan

as to get a lick from one o' them fists! " The engines at

that time were all named instead of being numbered, and the "Donnegan"

was one of the largest on the road.

In June of this year,1860, I fell

in love with a black-eyed girl, between fifteen and sixteen years

of age, and when I was off duty, spent the most of my time with

her. After a month or two, I mustered up courage to ask her to

be my wife. She was willing, but told me that she was too young

to marry then, and wanted to wait a year or two. I told her I

didn't want an old wrinkled woman for a wife. In June of this year,1860, I fell

in love with a black-eyed girl, between fifteen and sixteen years

of age, and when I was off duty, spent the most of my time with

her. After a month or two, I mustered up courage to ask her to

be my wife. She was willing, but told me that she was too young

to marry then, and wanted to wait a year or two. I told her I

didn't want an old wrinkled woman for a wife.

By the way, she reminds me sometimes in later years, that I

didn't want an old wrinkled woman for a wife, but that I possess

one. "Yes," I reply, "but the wrinkles and bald

head have come to us while, during an ordinary lifetime, we have

been plodding along together."

We talked the matter over, and the question came up as to whether

or not her father would consent to our marriage. He had business

away from Huntsville at that time and hadn't made my acquaintance.

I asked her if she would run away with me in case he refused his

consent, and she said she would.

A train left there about the middle of the night, and it was

just a short distance from her windows to the ground; so she said

if she had to, she would climb out of the window and leave with

me. Fortunately we did not have to take that step, as the parental

consent was cheerfully given.

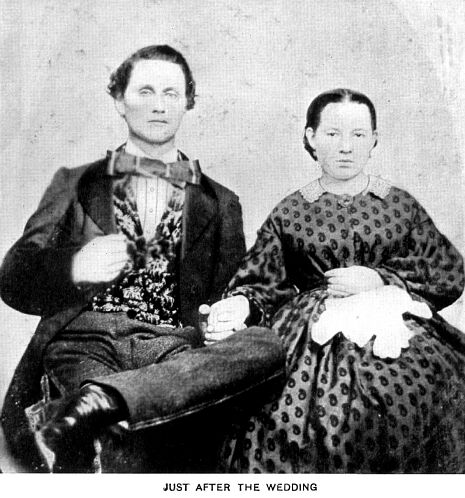

We were married in October after an acquaintance of four months.

The ceremony was performed by a Cumberland Presbyterian minister,

who, singular to relate, had baptized my wife when she was an

infant. His name was Chadwick.

We were both Methodists; my wife having been a member of the

church for two or three years, while I had joined a short time

before, during a big revival meeting at the old West Huntsville

church. At the time of the marriage, the ministers of the Methodist

churches happened to be away at Conference, and Brother Chadwick

had to leave for Presbytery the very next day. Thus we came very

near not getting married at that time, as my wife said she would

not be married by any other than a minister.

It was the custom then, to marry at night, with a supper after

the ceremony. We invited as many of our friends as we could possibly

accommodate, and had an up-to-date supper.

A tall pyramid of cake adorned the centre of the table, the

bottom layer being almost the size of a half-bushel, then diminished

until the topmost one was the size of: a teacup. It was all beautifully

ornamented, and presented a lovely appearance. The various other

accessories I cannot now recall, except that we had boiled custard.

Ice-cream was substituted for this delicacy later on in years,

but in those days just the boiled custard, in cups, was served.

The bride was dressed in white embroidered swiss, with low

neck and short sleeves. I don't know how she seemed to others,

but she looked beautiful to me.

Feeling like a man, then, I decided to ask for a raise in wages,

as I was then getting only $1.50 per day. Accordingly I went to

"Uncle Jimmie " and told him that I thought he ought

to pay me more, as I worked early and late, and put in more hours

than any man around there. He said he would, "see about it,"

and did raise my wages twenty-five cents on the day.

I kept my same position there until the twentieth of December,

when I got leave of absence to go to Georgia to visit Father and

Mother, and show them what I had found in Alabama.

Our visit was pleasant, with the exception of two incidents

that got me into fights. I came out victorious in both cases,

and had right on my side, but thought I had better go back to

Alabama before getting the reputation of being "a fighter."

When I got back to Huntsville and reported for duty, "Uncle

Jimmie " informed me that he had put a man in my place. I

remarked, "Well, I am out." His reply was, "No,

I gad, ye are not; I am going to put you in road service, and

give you a construction train."

This promotion took place in January, 1861, and as a full-fledged

engineer, I started on my career of a halfcentury. Though all

these years have passed, I still recall every detail of our lives

during those first months "on the rail."

Our stopping place at night was out in the woods, four miles

above Iuka, Mississippi, at a place called Gravel Siding. After

a few days I sent for my wife, and it was a happy meeting when

she got there.

We boarded for a short time with a family by the name of Castleberry.

The family either had to live hard, or, wanted to, I don't

know which. Our fare consisted of corn bread, fat meat, swimming

in grease, and cow-peas; with coffee for breakfast in place of

peas.

My Frances had a rough time as far as eating was concerned,

for she was not fond of corn bread, didn't like fat meat, had

no use for cow-peas, and didn't drink coffee. She would see biscuits

in her dreams, but would awake to the sad reality of big corn

pones.

She was so anxious to "keep house" that I secured

a little one-room shanty, and we went to housekeeping.

Our dwelling had two doors, no window, and a stick and mud

chimney. My wife didn't know how to cook, but set in with a determination

to learn; so we got on very well, arid were as "happy as

larks." We got a better place, after a few weeks, and had

a couple living in the house with us for company.

Our chief amusement while there was shooting. We would "side

track" for trains to pass, and then while away the time shooting

at a mark. The conductor, my wife, and myself would compete, and

Frances nearly always came out "first marksman."

We enjoyed everything that came in our way in those days. Wood-rats

were in abundance, also stray cats, that wouldn't catch the rats.

One night a big rat bit one of Frances' toes, and one day, while

eating a meal, a cat came in. I looked about to get something

to throw at it, and the nearest thing that seemed to be suitable

was a piece of light-bread that our neighbor had given us. Frances

couldn't make light-bread, and would eat on that piece very sparingly,

to make it last as long as possible. She was about to reach for

the bread to finish it (for it was pretty hard by this time) when

I grabbed it up and gave that cat a whack with it. She had climbed

up the side of the house, which was only weather-boarded, but

the aim was true, and she speedily descended and scampered away.

We have laughed many times about the precious bread and the visiting

cat.

Table of Contents

| Next Chapter | Contents

Page

|