|

CHAPTER VI—A WRESTLING MATCH; NARROW ESCAPES

IN those days also we had men who prided themselves on their

wrestling powers, and our road possessed such a wrestler. He told

me several times that he wanted a chance to put my back on the

floor, as he had thrown all the other men on the road. I advised

him to leave me alone, but he was so anxious to get his hands

on me that he came to my room one bright morning, and said he

had let me off as long as he could, and that I was going to have

my back on the floor before leaving that room. I tried to argue

him out of it, telling him that the floor was a hard place to

strike against, but he wouldn't listen to anything I said, except

to reply that it was my lookout if the floor was hard, for he

didn't expect to come in contact with it. Finally, seeing

that nothing else would content him, we went at it. We had it

around and around, until at length, getting him just like I wanted,

I picked him up and threw him as hard as I could against the floor,

without going down myself. The noise of his contact with the floor

could have been heard a quarter of a mile, and when he got up

he left the room holding his hand to the back of his head. The

champion wrestler did not care to put his hands on me any more

after that, having learned that size and weight don't "cut

much figure" against strength and muscle. We have been good

friends ever since then, and this brother now heads the seniority

list of engineers on the Mobile Division of the Southern Railway.

Looking backward, I now realize that those days were among

the brightest and most pleasant of my railroad career. Our regular

train consisted of ten freight cars and three coaches, when they

had them, and they nearly always did, when business was good.

Our schedules were not very fast, we had good engines to run,

and I had a long lay over with my brown-eyed girl and little ones.

I was paid at that time $4.00 per day. My lay over at home was

two days and one night. We did all the work of our own engines,

and as a general thing, I put in one half-day out of three in

this occupation. We didn't have metallic packing then, using altogether

fibrous packing, hemp, etc. I would pack my engine about twice

a year. The Master Mechanic once asked me what I used for packing.

I replied that I used hemp. He said, "There hasn't been any

charged to your engine in six months." I told him that I

only packed her every six months, and then I did the work well,

so that I wouldn't have to be working all the time.

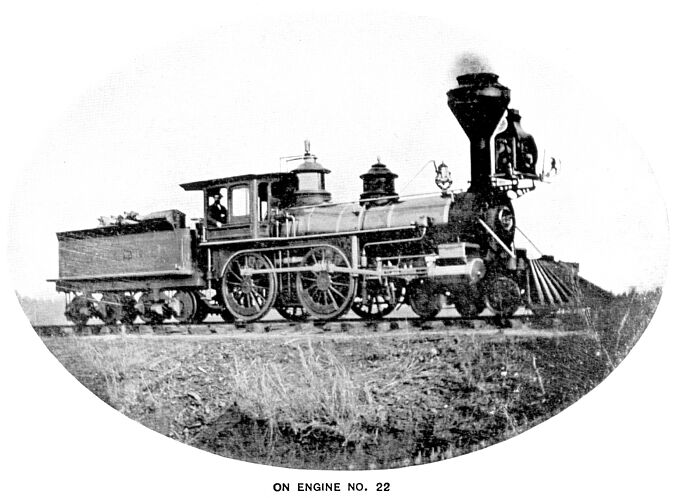

During a space of ten years I usually ran one engine, No. 22.

Before the war the engines were all named, generally after big

railroad men, or their wives, such as the "Sally Walker,"

"Belle Kelser," and "Myron L. Stanton." With

the close of the war the system of numbering began. The Twenty-two

was then considered the mammoth engine of the South, having a

fifteen by twenty-four-inch cylinder, and weighing thirty tons.

She was a beauty! Of symmetrical proportions, gilt-trimmed, and

always spick and span,—for that was previous to coal-burning

days, and little time and trouble were required to keep the engines

trim and shining. It was an easy matter for the Twenty-two to

make fifty miles an hour, and she burned three cords of wood in

a round trip, her entire expense, including engineer's and fireman's

wages and all repairs, amounting to only eight or eight and a

half cents per mile. Frances often expresses regret that the engines

have now become so big, black, and ugly, and minus the red or

gilt stripes they so lavishly displayed in the days of the Twenty-two.

In the spring of 1877 occurred the only derailment I have had

in forty years, caused by running over a mule. The accident took

place at the mouth of a bridge near the station now called Jenifer.

The engine dropped through it, being completely wrapped up in

the bridge structure even with the stack, and all went down together.

When I saw the crash coming, I sprang from the cab out on the

front end, and holding to the head-light bracket, escaped uninjured

from the wreck.

Another accident occurred five months later, however, in which

I was not so fortunate. Through fault of the despatcher, there

was a head-on collision between Talladega and Alpine. We met on

a curve, and when I first sighted the engine, she was only sixty

yards away, with the distance rapidly diminishing from both directions.

There flashed through my mind the thought that I had never seen

such enormous figures as those two forming the 20 on that number

plate,—and then I jumped! Landing on a crossing, my foot

slipped, and I fell forward on my head. I was badly hurt, remaining

unconscious for several days. The opposite engineer—Jack

Linton—was killed, while both engines and two or three cars

were literally torn in pieces.

This same year the engineers evidently concluded that they

didn't need a Brotherhood, for one after another dropped out of

the Division, on account of nonpayment of dues, until just five

members remained, namely: Con and Dave Griffin, George Williamson,

George Stuck, and myself. All these brothers have years ago made

their final run into the Better Country, but at that time they

stood staunchly by the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers, and

made every effort to keep Division No. 26 alive, but we did not

have members enough to get together to hold a meeting oftener

than once or twice a year. At the end of two years, I wrote to

the Grand Chief, P. M. Arthur, telling him that we had not held

a meeting in twelve months, and asking what we must do. He promised

to come down and see us, but failed to do so. In 1879, we decided

to return the charter to the Grand Office, so there was nothing

done in the way of Brotherhood business until 1883, when Division

No. 223 was organized. I was not a charter member, but a few weeks

after the reorganization a committee was sent to ascertain why

I did not join. I replied it was on account of the way the men

had acted in the old division; that I had paid the expenses of

Division No. 26 out of my own pocket, excepting a balance still

due for hall rent; but finally told them that if they would agree

to settle up that indebtedness, I would become a member. They

promised to do so, and I joined.

I think it was in '79, when our youngest girl was a baby in

long clothes, that occurred one of my most horrible experiences

as an engineer. All trains were still coming in on the track not

more than fifty feet from our gate, and the schedule time of arriving

in Selma was shortly after nightfall. One evening as I came in

sight of our home, I saw, in the bright rays of the headlight,

the slim figure of a woman walking down the middle of the track

to meet the engine. When I blew the whistle, she moved to the

side away from me, and I thought she had stepped down clear of

the track, but the next moment my fireman said, "Mr. Thomas,

you hit that woman." I replied, "I guess not,"

being then engaged at waving at my wife and children who, with

a friend, stood just outside the gate. The fireman insisted saying,

"I saw her fall, Boss." And sure enough the woman was

found lying there unconscious, with a great hole in the back of

her head. One slipper had been thrown fifty yards down the track

one way, and the other almost that distance in the opposite direction.

The lady had been over to visit my wife, and lived only a short

distance on the other side of the railroad. She was carried to

her home and died in less than half an hour, without ever regaining

consciousness. Of course, the affair made me feel dreadfully,

though I was not to blame, and could have done nothing more to

prevent the accident.

Table of Contents

| Next Chapter | Contents

Page

|