The Trade of Train Robbery

Munsey's—February, 1902

by CHARLES MICHELSON

THE HIGHWAYMAN OF THE RAILROAD HAS TAKEN THE PLACE OF THE OLD

TIME FOOTPAD. IN CRIMINAL SOCIETY HE IS DEEMED A LEADER, A MAN

WORTHY OF THE RESPECT OF HIS FELLOWS. HIS CALLING IS THE MOST

DANGEROUS OF ALL ILLEGAL PROFESSIONS. HOUNDED BY SHERIFFS' POSSES

AND VIGILANCE COMMITTEES, HE STILL LIVES—A MENACE TO ALL

SOCIETY.

TRAIN robbery has been a recognized branch of criminal industry

for nearly forty years, yet the advance in it has been far less

than might be expected of a pursuit that has, at one time or another,

attracted the shrewdest as well as the most daring and enterprising

of the criminals of America. The gross receipts by train robbery

have averaged not far from one hundred and fifty thousand dollars

a year, and, as not more than twenty thieves ordinarily share

this booty, it is not difficult to understand why men follow it

in spite of its dangers. The large proportion of the best exponents

of the craft are dead or in penitentiaries, but the train robber

is a lord in the kingdom of crime. In all the penitentiaries of

the West he rules the common run of law breakers.

The flashiest burglar in stripes, even if he has the red device

of murder on his coat of arms, is glad to maneuver to become cell

mate to the man who is there because he held up a train. For him

the caged thieves and thugs fetch and carry and offer their tribute

of tobacco and contraband comforts, and to him is offered the

captaincy of projected jail break. But the industry is appallingly

conservative.

In forty years there has been only one conspicuous advance.

It has not kept pace with the progress of related arts. For this

reason, it has become the most hazardous of crimes—not in

the commission, that is astonishingly easy; but in the getting

away. In a country cobwebbed with telegraph lines and honeycombed

with detective agencies, with their disheartening outposts of

stool pigeons and informers, escape is yearly getting more difficult.

The one advance is the use of dynamite for the forcing of the

express cars. What may be obtained from passengers is merely a

by product, and is ignored by many distinguished bandits as involving

more trouble and risk than the probable yield justifies. It has

come to be the practice merely to fire a perfunctory volley along

the train side to warn the passengers to stay inside and mind

their own business, and then to devote whatever there is of time

to the treasure cars.

THE FIRST TRAIN ROBBERY

Except for the dynamite, the first train robbery might have

been one that took place a week ago, so far as method is concerned.

It happened on the Ohio & Mississippi road at Brownstown,

about ninety miles from Cincinnati. Two men appeared on the tender

of the locomotive and covered the engineer and fireman with revolvers.

They made the engineer stop and uncouple the express car, then

haul it five miles down the road. They forced the messenger to

open the safe, and they realized twelve thousand dollars by the

new method of depredation. This was in 1866. Credit for the robbery

was given to a family named Reno, but the express company failed

to prove aught against them. It made little difference, however,

for the Renos were caught robbing trains soon after and were lynched

by a mob at New Albany, Indiana. This was before the guerrillas

left without employment by the end of the Civil War took to train

robbery and made it popular.

The first train robberies caused a panic all through the country.

The advent of the railroad in the place of the stage coach had,

it was confidently announced, eliminated the road agent from the

perils of travel, and here was the old thing in an aggravated

form. In the midst of all the excitement, there was another hold

up, one which remains unique in the history of train robbery.

Two boys of Brownstown were the robbers. They carried out the

program so well illustrated by the Renos and captured the treasure—three

thousand dollars—but their parents learned of their exploit,

and delivered them to the police with the treasure. A sound thrashing

by the fathers of the two boys was the punishment the authorities

thought fitting, and it was administered. One of these boys went

to Congress a long time afterwards, and the other became mayor

of a neighboring city.

THE TRAIN ROBBER TRUST

For a few months the Renos had a monopoly of the train robbing

business. There were four brothers of them, Frank, Jesse, Sim,

and Jack, and they took in a relative named Anderson as partner.

Their greatest exploit was the capture of an Indianapolis, Madison

& Jefferson train near Seymour, from which they gleaned one

hundred and thirty five thousand dollars. Carrying their great

plunder, they got away to Canada, where they were finally caught.

With all this money, they were able to put up a strong legal fight,

and for a long time it looked as if they would not be extradited.

The lynchings took the zest out of train robbery for several

years, but when it was resumed it was in a form that doubled the

terror the early seizures had caused. It was in 1870 that train

wrecking as a means of train robbery came into vogue. Eight men

tore up the track of the Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific road

near Council Bluffs and waited for the overland. It came, crashed

over the break, killed the engineer, and injured a score of passengers.

As the train went over, the robbers sprang from their hiding

places and went to plundering the wounded. They were successful

in robbing the passengers and in addition got six thousand dollars

from the express car. Thirty-thousand dollars reward was offered

for the capture dead or alive of these robbers, but nothing came

of it. The enormity of the crime forbade that any of those who

took part in it should ever disclose his participation even to

other criminals, and nothing was ever learned.

This horror stopped train robbing for five years; there were

no criminals desperate enough to work in the face of the storm

caused by it. Except for one desperate failure in 1870, when a

Vandalia engineer was shot and killed, the country heard nothing

of train robbers until the James and Younger boys began their

long course of crime.

The glamour of the fugitive guerrilla was theirs, and the Robin

Hood reputation they built up stood them in good stead. They were

wholesale outlaws, and there is no room in a magazine article

for a circumstantial account of their wonderful career. They realized

at least one hundred and fifty thousand dollars from half a dozen

train robberies, not counting the considerable sums they took

from passengers. The passengers they killed when they failed to

part easily.

Yet they had the countryside so surely with them, that rewards

aggregating seventy thousand dollars went unclaimed until one

of their own number turned traitor and shot Jesse James in the

back.

Bob Ford had seen men killed in train wreckings, and could

not understand why he should not realize a comfortable fortune

by the equally simple method of killing his outlaw chief. So he

murdered him.

CALIFORNIA'S QUOTA

It was with this same spirit the law officers had to contend

in California, when, later, it became the happy hunting ground

of train robbers. A long time ago the Southern Pacific Railroad

had trouble with squatters on some land to which it obtained title

through the courts. The settlers were expelled. If they resisted,

they were shot. Since that time, through all of that section the

name Mussel Slough is sufficient reply before a jury to the most

rousing eloquence and the most convincing evidence the railroad

can invoke.

In this country a small farmer worked a little patch of ground,

and hired out as a harvest hand when his own little plot did not

require his attention. He was a middle aged, red bearded man,

with a large family. With them in the cramped farmhouse lived

two young men, John and George Sontag, as industrious and commonplace

as their host, whose name, by the way, was Christopher Evans.

The whole outfit was about as inconspicuous as any in Visalia,

itself a remote town that fell asleep when the railroad left it

eight or ten miles off the line in punishment for having failed

to give all that was asked in the way of depot sites. In time

Visalia got a branch line, but that did not avail to wipe out

the past sins of the Southern Pacific Railroad. For a dozen years,

train robberies on the line occurred with frequency, and the perpetrators

went unpunished.

Much of the robbery was credited to the Dalton gang, but the

Daltons cleared out for Missouri and Oklahoma and the robberies

did not cease. Once or twice an inquisitive passenger who could

not keep his head inside the car window while the robbers were

blowing open the express car was killed, but as a rule the travelers

were not molested. Finally a train was robbed in the usual fashion

at the usual place. The mail and express cars were looted, the

messenger was half killed by the explosion of a great charge of

dynamite against the door of his car, the fireman was forced at

the pistol's point to climb through the ragged hole and to open

what was left of the door. When it was all over the bandits went

off in a cart.

THE EVANS GANG

Among the passengers who came into

Visalia from the held up train was George Sontag. Him the sheriff

interviewed as a witness before starting out on the man hunt.

He told a vivid story of the affair, furnished a description of

one of the robbers, and then went home to the Evans house. Among the passengers who came into

Visalia from the held up train was George Sontag. Him the sheriff

interviewed as a witness before starting out on the man hunt.

He told a vivid story of the affair, furnished a description of

one of the robbers, and then went home to the Evans house.

It happened that the conductor of the train knew George Sontag,

and had not observed him among his passengers until after the

hold up. Then the Wells Fargo men came in with the news that they

had followed the tracks of the bandits' cart to near the Evans

ranch. The identity of the robbers who had done so much to make

travel on California railroads exciting was revealed in a flash.

A fine trap was immediately laid. A messenger was sent to ask

George Sontag to come to the sheriff's office to identify a suspect.

He went and was promptly locked up.

A strong force then went to the Evans place to get Chris Evans

and John Sontag, but the clever thief takers at the sheriff's

office had left out of the calculation the feeling of the community.

Word of George Sontag's arrest reached the Evans house before

the posse did, and while the officers were surrounding the place

the door of the Evans barn flew open, two shotguns poured out

buckshot, and the posse recoiled in disorder. When the shattered

attacking line reformed it was to find Chris Evans and John Sontag

gone, and the best deputy in Southern California lying with his

hands full of turf in the Evans dooryard. Others of the posse

were wounded as well, but neither Evans nor Sontag was hurt.

THE ROBBER FUGITIVES

Then began the second stage of the train robbers' life—that

of the fugitive. For a year the pair dodged about the mountains,

and the rewards for their apprehension steadily mounted until

they were worth ten thousand dollars to anybody who would betray

them; yet during all that time they were being harbored by men

to whom ten thousand dollars represented more of wealth than they

expected to garner in a lifetime.

I save stood with a posse in a cabin while a detective was

bargaining with its toil worn proprietor to lure the two hunted

desperadoes to their undoing, when all the time Evans and Sontag

lay under the hay in the barn not a dozen yards from the cabin

door. I have listened to woman—as bad and as hard a woman

as ever preyed on a drunken lumberman—promise to send word

as soon as the men made their appearance at the mountain den where

she and others of her kind faired. I have seen her beg a pittance

of the price of her perfidy on account, when all the time she

knew the two lay asleep in the very building.

I even remember a man, a gaunt old criminal, one who had murdered

a Chinese laborer to save the wages he owed him, undertaking to

earn the reward by guiding the posse to where the outlaws were

hiding, admitting as he did so that but a day or two before then

had been his guests in his ranch house. He guided the officer;

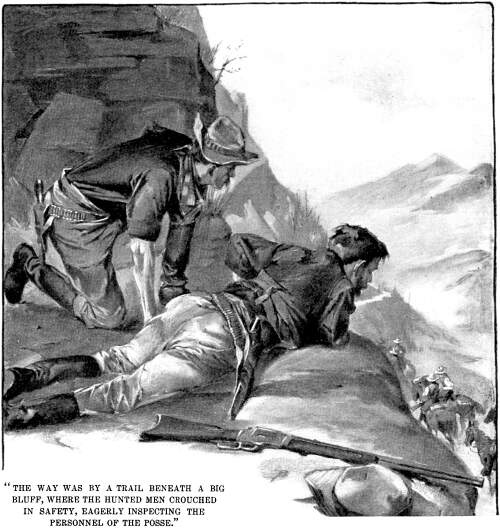

to a camp that had been abandoned by Evans and Sontag. The way

was by a trail beneath a big bluff, were the hunted men crouched

in safety, eagerly inspecting the personnel of the posse the old

rascal had promised to show them.

Neither he nor any of the people of the hills would stretch

forth a hand to grasp the reward offered them.

Occasionally the pursuers came up with the pursued. Once this

happened at a cabin where there was no reason to suspect their

presence. As the posse came up, a hill roustabout stepped from

the hut and without a word walked to the spring for a bucket of

water, giving no warning. A moment after, Evans and Sontag jumped

out, their guns at the shoulder. When the remnants of the posse

came back, Vic Wilson, professional bad man hunter imported from

Arizona, and Andy McGinnis, a man hunter of equal local fame,

had been left dead on the door step. The fugitives were away again.

It was not that the rest of the posse were unfit for their

work—there were good men among them—but the attack had

been so swift and the surprise so complete that fear, which comes

before courage, got such a start that the nobler quality was unable

to overtake it. They never found any wounded after Evans and Sontag

had been left in possession of a field. They always put a gun

to the ear of a prostrate foe, when there was time, and blew his

head off.

The next ambush in this long chase was on the other side. The

sheriff's men hid for three days in a cabin at the foot of a hill,

and on the fourth morning were rewarded by the appearance of their

long sought quarry. The outlaws, however, saw the trap in time

to drop behind a heap of manure that made an admirable fort. They

had the up hill of their foes, and were able to fight an all day

battle. As each of, the robbers carried a rifle, a shotgun, and

two big revolvers, there was no lack of shooting.

The law officers had excellent

cover, and the end of a long day found them all alive, though

one had a ball shattered leg, while the two outlaws behind the

stack were variously shot up. At dusk, Evans staggered away through

a storm of bullets, and the posse let the other alone till the

chill of morning should stiffen his wounds. Then they gathered

him in. He was John Sontag, and ultimately died rather than have

his limb amputated. The law officers had excellent

cover, and the end of a long day found them all alive, though

one had a ball shattered leg, while the two outlaws behind the

stack were variously shot up. At dusk, Evans staggered away through

a storm of bullets, and the posse let the other alone till the

chill of morning should stiffen his wounds. Then they gathered

him in. He was John Sontag, and ultimately died rather than have

his limb amputated.

Evans was rounded up at the home of a relative, and, barring

the loss of an eye and a hand, was as good a man as ever when

the surgeons got through with him. He charmed the waiter who brought

him his meals from the outside, with stories of outlaw life, persuaded

him that he was of the brood of bad men, and, with his help and

the influence of certain revolvers brought in under the napkin,

succeeded in getting clear away.

Winter's cold and his newly healed wounds were too much, however,

even for Evans, and they rounded him up. All the glory the waiter

got out of it was the privilege of sharing his penitentiary life

with the train robber. With all the murders the law could prove

on Chris Evans, it could not hang him, and he is still in the

prison at Folsom, a life prisoner, with George Sontag, who, after

an unsuccessful attempt at breaking jail, finally went on the

witness stand and testified against his former partner in crime.

THE DALTON GANG

It was never quite settled whether the Evans-Sontag gang and

the Daltons worked together, though in all probability they did.

They both worked about Tulare, California, though after a time

the Daltons moved away to the middle West. There they roamed until

the band came to an end which was more fitting and more thoroughly

complete than that of any other outlaw gang on record.

Bill Dalton the oldest of the brothers, was perhaps the handiest

man with a .44 Winchester that ever pulled trigger. He never raised

his rifle to his shoulder, but let go, pistol fashion, from the

hip, and so true was the relationship between eye and hand that,

in his peaceable hours, they used to bar him from turkey shoots,

because at two hundred yards he tumbled the birds as fast as they

were released. His record showed that Bill Dalton could shoot

men as well as turkeys, which is not altogether a common thing

even in Indian Territory, where no close season for either, is

observed.

A HISTORIC HOLD UP

The hold up of a train near Adair,

in which all three of the Dalton brothers took part, was enough

to give any gang a reputation. Hold ups had been so frequent that

the trains were carrying guards, and on this particular train

there were twenty armed men charged with protecting passengers

and express. But the Daltons swooped down on the train when and

where they were least expected, and kept a streak of rifle fire

going along the sides of the cars that made it absolutely impossible

for a man to show his head and keep that head on. The dead and

wounded demonstrated that. The robbers cleaned out the express

car as usual. The hold up of a train near Adair,

in which all three of the Dalton brothers took part, was enough

to give any gang a reputation. Hold ups had been so frequent that

the trains were carrying guards, and on this particular train

there were twenty armed men charged with protecting passengers

and express. But the Daltons swooped down on the train when and

where they were least expected, and kept a streak of rifle fire

going along the sides of the cars that made it absolutely impossible

for a man to show his head and keep that head on. The dead and

wounded demonstrated that. The robbers cleaned out the express

car as usual.

Their adventures and exploits after this make a long story.

They killed many people, and stole hundreds of thousands of dollar,

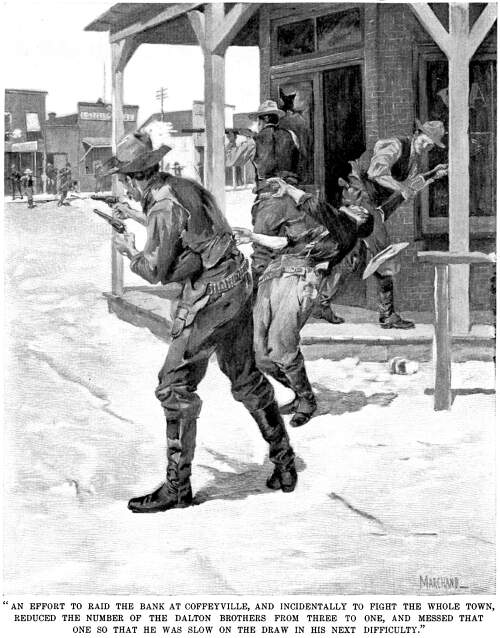

but it was all evened up at Coffeyville, Kansas. An effort to

raid the bank, and incidentally to fight the whole town, reduced

the number of Dalton brothers from three to one, and messed this

one—the redoubtable Bill—up so that he was slow on the

draw in his next difficulty and joined his brothers on the other

side of the great divide. The Coffeyville affair was the greatest

clean up of train robbers the country ever had: nearly every one

who fell before the Winchesters and shotguns of the citizens had

achieved eminence in this line.

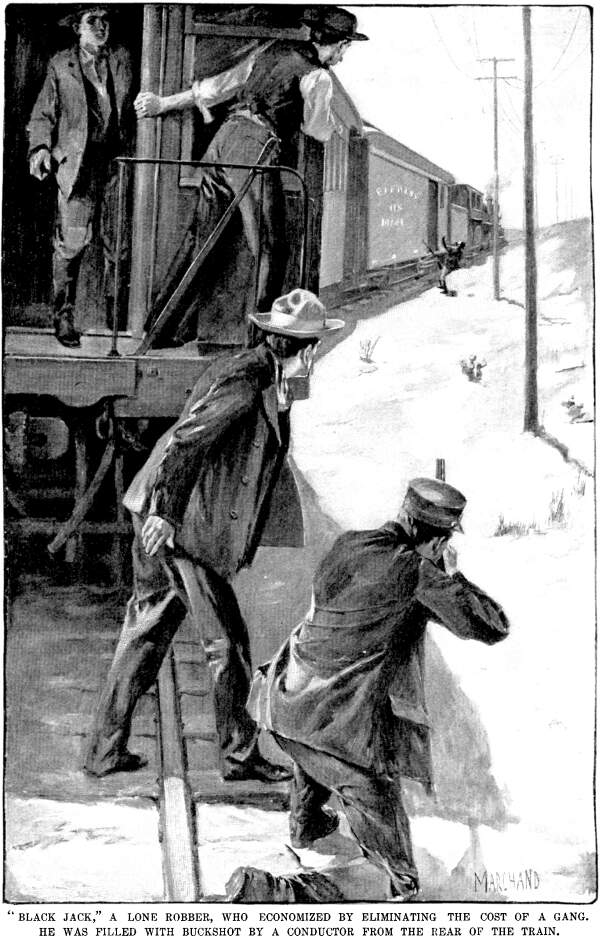

It is only two years since the "Black Jack" band

that terrorized trainmen in the Southwest was rounded up. Black

Jack's real name was Tom Ketchum. He operated for four years before

they got him. His undoing was the result of avarice.

So long as he worked with his gang, Black Jack kept clear of

the law, but one day he found it was possible to hold up a train

single handed and so to avoid any division of the proceeds. He

was trying this on the Texas Express when a conductor jumped off

the rear of the train and filled him with buckshot. The gang did

not long outlast the chief's misadventure.

Stories Page | Contents Page

|