|

Scientific American—February

17, 1912

How Railroad Men are Made

Training the Men Who Run Big Railways

By P. Harvey Middleton

IN 1912, with

our railroads forming a gigantic network of 240,000 miles, representing

an investment of twenty-two billions of dollars, earning for their

owners over a billion dollars every year, carrying a billion passengers

and two billions of tons of freight in the twelve months, necessitating

the employment of 1,700,000 persons more than twelve times the

combined strength of our army and navy the requirements of railroad

men of all grades, from track walker up to president are exacting

in the extreme. Professional training, a clear head, steady nerves,

and strong muscles are some of the requisites, but training is

the most important of all. The old style of railroad man who could

not read a blue print or make a freehand sketch, would be as useless

a cog in the mighty wheels of our transportation system as the

superb courage of the Mahdi's troops was when opposed to discipline

and breechloaders. IN 1912, with

our railroads forming a gigantic network of 240,000 miles, representing

an investment of twenty-two billions of dollars, earning for their

owners over a billion dollars every year, carrying a billion passengers

and two billions of tons of freight in the twelve months, necessitating

the employment of 1,700,000 persons more than twelve times the

combined strength of our army and navy the requirements of railroad

men of all grades, from track walker up to president are exacting

in the extreme. Professional training, a clear head, steady nerves,

and strong muscles are some of the requisites, but training is

the most important of all. The old style of railroad man who could

not read a blue print or make a freehand sketch, would be as useless

a cog in the mighty wheels of our transportation system as the

superb courage of the Mahdi's troops was when opposed to discipline

and breechloaders.

From this it may be seen that the education of apprentices

on a twentieth century railroad is the most important problem

of the company. Just as the United States Government has a West

Point and an Annapolis for the training of its future admirals

and generals, so our great railroad systems all have training

schools for the production of educated workmen, foremen, and superintendents

academies where the raw recruit is initiated into all the mysteries

of railroading, from the making of drawings to the assembling

of locomotives, which later grow before his eyes from nondescript

heaps of metal and pass out into active service. He helps to build

these leviathans of the rails, and to repair them when they come

limping back, strained from overwork or torn to pieces by collision.

Let us follow the various stages in the career of one of these

novices during his four years apprenticeship in Railroadville.

We will call him William Smith. He has applied to the general

manager of the road, John Brown, for admission as an apprentice.

Brown sees that he is an intelligent-looking chap and cross-examines

him as to his mental and moral fitness.

"We have

two grades of apprentices," says Brown; "special and

regular—all of whom stay here three years. The boy with a

public school education is drafted into the regular class, to

train for the rank and file. The special must be a college graduate,

and qualify for the higher positions. Take my advice, Smith, graduate

from your college, and we will admit you as a special. But remember

this; it is four years of solid hard work and precious little

play. Ten hours a day, 304 days a year, you will have to work

in the shops. You will work under the superintendent of the motive

power department, and do whatever he orders—crawl into the

warm fireboxes of locomotives, sweat in the glare of a white-hot

furnace, wield a hammer in the ear-splitting din of the boiler-room,

or paint the interior of a parlor car. It's all in the day's work.

The reward? Well, it depends on your ability. The salaries of

railroad men range all the way from $500 to $50,000 a year. When,

you have had your training, it's up to you." "We have

two grades of apprentices," says Brown; "special and

regular—all of whom stay here three years. The boy with a

public school education is drafted into the regular class, to

train for the rank and file. The special must be a college graduate,

and qualify for the higher positions. Take my advice, Smith, graduate

from your college, and we will admit you as a special. But remember

this; it is four years of solid hard work and precious little

play. Ten hours a day, 304 days a year, you will have to work

in the shops. You will work under the superintendent of the motive

power department, and do whatever he orders—crawl into the

warm fireboxes of locomotives, sweat in the glare of a white-hot

furnace, wield a hammer in the ear-splitting din of the boiler-room,

or paint the interior of a parlor car. It's all in the day's work.

The reward? Well, it depends on your ability. The salaries of

railroad men range all the way from $500 to $50,000 a year. When,

you have had your training, it's up to you."

"I'll come when I graduate next year," replies Smith,

quickly.

And a year later Smith gets out at Railroadville with his grip.

That preliminary talk with Manager Brown has prepared him somewhat

for the simple strenuous life. He hires a small room in a boarding

house kept by the widow of a railroad man. For the first day or

so the meals and the drab atmosphere of the place induce a severe

attack of homesickness. But the antidote of hard work soon replaces

that with an appetite which the habitué of

the foremost restaurants might well envy.

On his first week in the shop he is sent to the erecting room,

where he studies the different parts of a locomotive and is taught

the work they perform. When he has proved that he has thoroughly

absorbed this knowledge, an old hand takes him inside a defective

boiler, and under the experienced man's direction he repairs it.

After six months of this sort of work his hands have become so

rough and calloused, and his, general appearance so dusty and

grimy, that it is hardly probable that the girls back home would

recognize their dancing partner in this hardy son of toil; and

his fellow apprentices in the special class-one a senator's son,

another the son of the president of the road-are similarly disguised.

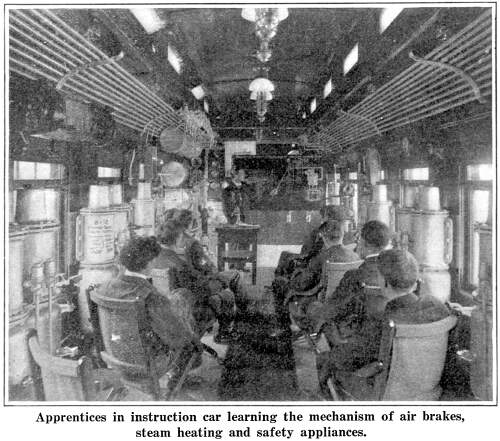

Smith now

goes to the machine shop for six months, in order to learn how

to operate the great lathes which are used to shape the steel-powerful

yet delicate pieces of mechanism which cut the steel to the required

form as easily as a planing mill shapes pine boards. Then come

three months in the vise shop, where instruction is given in the

fitting and polishing of driving rods and the finishing and adjusting

of valves. This is followed by two months in the airbrake shop,

and two months more in the blacksmith shop, where he is taught

the working of the big steam hammers, the heavy sledges, and the

giant forges. Smith now

goes to the machine shop for six months, in order to learn how

to operate the great lathes which are used to shape the steel-powerful

yet delicate pieces of mechanism which cut the steel to the required

form as easily as a planing mill shapes pine boards. Then come

three months in the vise shop, where instruction is given in the

fitting and polishing of driving rods and the finishing and adjusting

of valves. This is followed by two months in the airbrake shop,

and two months more in the blacksmith shop, where he is taught

the working of the big steam hammers, the heavy sledges, and the

giant forges.

A course of two months in the foundries, casting and molding,

is followed by two months in the boiler shop and this latter is

the most trying period of his apprenticeship; for he is called

upon to work amid the din of hundreds of hammers smashing against

the iron ribs of great boilers, a deafening and distracting turmoil

which results in some sleepless nights for Smith until he becomes

accustomed to it—as he soon does.

The next class room in this strenuous schooling is the car

department, where four months are spent in the freight shop and

two in the passenger car shops, where Smith thoroughly masters

the building of everything on rails, from a hand car to a Pullman.

Then come four months in the roundhouse—the garage of the

railroad where locomotives in active service come in between the

runs to be inspected and cleaned. Then Smith's apparently endless

mechanical training is brought to a close by three months' duty

as fireman on the road.

Now for the

final year, to be spent in the cleaner but none the less strenuous

business departments. Shedding his jumper and overalls, Smith

enters the office of the shop clerk, and for two months he studies

the ordering and distributing of supplies. Graduating from this,

he places himself at the disposal of the motive power clerk for

another two months, learning the elaborate system by which locomotives

are built and dispatched to the various important points. Now for the

final year, to be spent in the cleaner but none the less strenuous

business departments. Shedding his jumper and overalls, Smith

enters the office of the shop clerk, and for two months he studies

the ordering and distributing of supplies. Graduating from this,

he places himself at the disposal of the motive power clerk for

another two months, learning the elaborate system by which locomotives

are built and dispatched to the various important points.

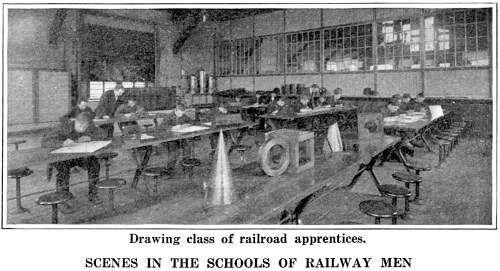

Five months must now be spent in the testing room, where he

watches the railroad chemist testing the steel alloy used in the

construction of axles, tires, boiler plates, and frame plates.

His apprenticeship winds up with three months in the drawing room,

and Smith becomes the proud owner of an honestly won diploma,

which enables him to obtain an executive position from which he

can climb to the highest salary in the gift of the road. He is

a railroad man in the truest sense of the word, of the stuff that

presidents are made of.

Where are these railroad academies? Well, the Pennsylvania

Railroad has one at Altoona, Pa., the Santa Fé system has

twenty-four schools, the New York Central has schools in nine

of its shops in the United States and one in Canada. The Grand

Trunk, Erie, D. L. &. W., D. & H., Jersey Central, and

Chicago Great Western all have similar schools.

The Union Pacific has a very extensive educational system.

In addition to the correspondence work, a station training school

has been established at Omaha to prepare men to enter the station

service of the company. This station school is equipped similarly

in all respects to a regular station of medium size, and is under

the direction of one of the company's experienced agents. All

men entering station service on the system are required to pass

through this station training school before being employed.

In the regular classes applicants are required to state their

previous education and experience; whether they are subscribers

to any technical magazine; whether enrolled with any correspondence

school; in what line of work they wish to advance; and to what

position (in reason) they are ambitious to attain.

The Canadian Pacific, at its Angus works in Montreal, has also

recently inaugurated a new system of training employees; and in

order to encourage deserving apprentices, the company donates

each year a scholarship to the best ten apprentices, consisting

of complete courses in mechanical or electrical engineering. The

railroad also awards two scholarships, tenable for four years

at McGill University, Montreal.

The young clerks in the general and other offices at Montreal

have equal opportunities with the apprentices in the shops for

equipping themselves for their life work. Schools of telegraphy

and shorthand have been in operation for some time, and the advantages

they offer are being eagerly seized by a number of ambitious youths.

There are two terms each year, and the classes meet three evenings

a week, when the students of telegraphy are instructed in the

mysteries of the key, taught how to dispatch trains, etc.

Stories Page | Contents Page

|