|

St. Nicholas—1901

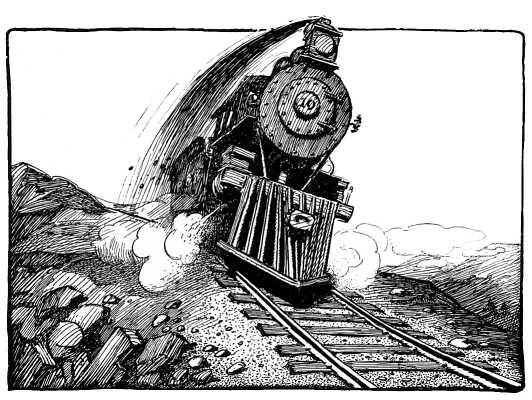

A RUNAWAY LOCOMOTIVE

By DAVID M. STEELE.

EVERY boy who

is as "boyish" as he ought to be has had, at some time

in his life, an overwhelming desire to be a locomotive engineer.

The size of the engine, the speed of its course, the mystery of

the signals, the lifelike motion of the iron creature, and the

element of danger involved in running it—all these appeal

to his imagination. They combine to persuade him that the only

profession worth choosing is that of the man who sits with his

hand on the throttle, his eyes fixed on the track before him,

and his hair streaming to the wind, while, with coaches coming

after him like riders on a bob-sled, he swings round curves and

dashes down grades at fifty miles an hour. EVERY boy who

is as "boyish" as he ought to be has had, at some time

in his life, an overwhelming desire to be a locomotive engineer.

The size of the engine, the speed of its course, the mystery of

the signals, the lifelike motion of the iron creature, and the

element of danger involved in running it—all these appeal

to his imagination. They combine to persuade him that the only

profession worth choosing is that of the man who sits with his

hand on the throttle, his eyes fixed on the track before him,

and his hair streaming to the wind, while, with coaches coming

after him like riders on a bob-sled, he swings round curves and

dashes down grades at fifty miles an hour.

I confess that although far past the age of a boy, I am not

yet beyond the fascination of all this. That is the reason why,

before starting on a trip to New York last summer, I applied to

a friend of mine, an officer of the Pennsylvania Railroad Company,

for an "engine permit" to ride on the engine over the

Western Division of the main line between Pittsburg and Altoona.

I rode on the fireman's side of the cab. From there I watched

the engineer. He was a sturdy man of forty-five, with strong muscles,

clear eyes, and cool nerves, who looked as if nothing ever could

excite him. He attended strictly to his work, and during the first

five hours of the run, that is, until we had gone through the

Gallitzin Tunnel and started down the eastern slope of the mountains,

he spoke only once to his fireman and not at all to me. Then,

at the very time when we were running fastest, and at the point

where I least expected it, he took his hand from the throttle,

leaned back, and began to talk to me.

"Everything here depends, not on me, but on the men in

charge of the track," he explained, when I expressed my surprise

that he should appear so careless here. "I am almost helpless

now if anything should be on the track—but nothing will be

on the track. This section is carefully 'walked,' and the switches

are in charge of 'old reliables.' We are running without steam,

on block signals, and have automatic brakes. There is little for

me to do except to wait while we drop down, down, down to the

foot of the mountain.

"'Running pretty fast?' Not so fast as once." Then,

prompted either by reminiscence or by that spirit of mischief

which causes Arab guides to tell tales of people falling while

they lead tourists down the sides of the Pyramids, he chose that

as the time and place to tell me the following story:

"It was during the first month that I was on the Pennsylvania,

twenty years ago. The thing had happened before and it has happened

since, but I had learned my trade on a prairie railroad, where

we did not have grades, and I had never heard of such an accident.

"I was 'freighting' then. Jim Gardner was my fireman,

and we two had charge of a big, old-fashioned, seventysix-ton

Mogul 'pusher.' Our business was to help freight-trains from Altoona

to the top, and run back empty on the east-bound track.

That morning we went up with a load of heavy cars, cut off

at Crestline, and started to drop back. We had 'turned the Shoe'

and were well out on the hill when I heard something snap. I looked

down at my drivers and then across at Jim. Without looking he

had known what the trouble was, and jumped. To this day I can

hear his yell, 'A runaway!' as he leaped into the bushes forty

feet below.

"The trouble was this: The brake was badly worn, so that

one sprag pressed more tightly than the other on its tire. The

undue friction heated it until it cracked. The broken piece flew

into the frame and tore away the king-pin. This let the whole

attachment drop to the ties and it was jerked away. The iron horse,

freed from this restraining hold, sprang forward like a stallion

from a broken tether, and started wildly down the mountain. Before

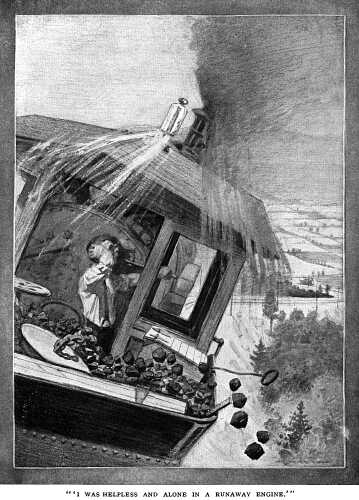

I realized that I could do nothing, and that it was useless for

me to stay, it was too late to jump. There I was, helpless and

alone, in a runaway engine.

"And how that engine did run! It seemed as if the drivers

were racing to catch the pilot-wheels, and neither could run fast

enough to satisfy the piston-rods. They bounded on the tracks

till every inch of gearing shook and rattled. The smoke-stack

toppled like the head of a dizzy man, while the boiler staggered

like his body about to fall. The steam-valve of the whistle was

jarred open now and then, and it gave little cries of fiendish

glee; while every minute we kept going faster and faster.

We had gone perhaps a mile before I could draw my wits together

sufficiently to think just what was the real danger. As I reasoned

the matter out it appeared to be threefold: we would either run

into something on the track; or some switchman, in order to save

other trains, would open a siding and 'ditch' us; or else we would

run on until the grade became so steep and the speed so great

that we would fly the track.

"We passed a block-station. The operator hung far out

of the window to watch us. Then I saw him turn to his instrument.

He was sending the word ahead, and the track would soon be cleared.

The first of the three dangers might be counted out.

"I reflected, too, that the second became less real inasmuch

as he had seen me; for I guessed, from the astonishment

he showed at seeing an engineer still riding, that I would have

been expected to jump. Now I reasoned that the switchmen would

be less likely to throw out the engine when warned that it carried

human freight. So I counted out that possibility.

"Still we ran.

We passed two more block-stations, with operators at the windows;

but we went so fast I scarcely caught a glimpse of them. The trees

flew away behind us as if trying to escape from something, while

telegraph-poles stood so close together that they looked like

upright bars across the window of the cab. "Still we ran.

We passed two more block-stations, with operators at the windows;

but we went so fast I scarcely caught a glimpse of them. The trees

flew away behind us as if trying to escape from something, while

telegraph-poles stood so close together that they looked like

upright bars across the window of the cab.

"So far we had no sharp curves, and although the road

ran in and out, I could see portions of it for three miles ahead;

but only portions, for sometimes it hid itself. You see how all

the way down here the road is built against the side of the mountain,

and that we are on the outside track. You see, too, if an engine

jumped the track where it would go. Well, I was looking away off

yonder when I saw an engine coming, head on, full speed up the

mountain. It disappeared after a little, then came in sight a

half-mile nearer. We had passed several trains, either running

or standing still, on the west-bound track, but what was my horror

when, on swinging into line with this, I saw that it was on

the outside track!

It disappeared again round a curve, and I tried to estimate

the distance. It could not be two miles off. I concluded that

they had decided to wreck my engine for the safety of the road,

and that to do this, another one, without an engineer, had been

sent against mine, and that the two would meet and be thrown over

the cliff at a point that was still out of sight.

What could I do? I tried to think. Once I decided to make a

wild leap for my life, but when I looked down the gorge my courage

failed me. I simply sat still, dazed, waiting for the awful crash.

"How long would it be? I waited what I thought was time

enough. Nothing happened. Then I waited again. Then I caught my

breath, and, when the strain became too great, I sprang to my

feet and looked ahead. There was an engine in sight, but it was

running from me.

"There was an engineer also, but he had come to save me,

not to wreck me. He had run as near as he dared, then stopped,

thrown his reverse lever, turned on full steam, and was now running

backward, at almost my own rate, ahead of me. It was desperate

work, but he gradually allowed my engine to catch up with his,

received the shock as easily as he could, then put on his brakes

and brought both under control."

That was before the days of air-brakes. "Runaways"

do not occur now; but when they did, that is how they were caught—when

they were caught. When they were not, they either wrecked

themselves, or something else, or both; and for many years they

were the most serious menace to railroaders on the, steep grades

of the Alleghanies.

Stories Page | Contents Page

|