|

Some Highways

and Byways of American Travel — 1877 Some Highways

and Byways of American Travel — 1877

A SWITCHBACK EXCURSION.

IT was on a pleasant morning in early spring that I met the

Artist and the Railroad-man at the depot of the North Pennsylvania

Railroad, prepared to take the cars for what the Artist, who is

addicted to punning, called "the Switcherland of America."

Our object was partly business and partly pleasure; in the proportion

of nine parts of the latter to one of the former: indeed, to be

quite honest about it, we were all glad to have an excuse for

a ten days' excursion in a region which promised so much outdoor

entertainment. And the promise was kept. Such another ten days

of rough-and-tumble experience-climbing mountains, falling over

rocks, exploring wild ravines, diving into coal-mines, riding

on every description of conveyance which it has entered into the

mind of man to invent to run on rail—such enormous eating

when we found an inn, and such extravagant sleeping when the day

was done,—I doubt if any of the party had ever experienced

before.

The direct route from Philadelphia to the Lehigh Valley and

the Switchback Railroad is up the North Pennsylvania Road, usually

called the "North Penn," for short. This road carries

you northward on a smooth, well-ballasted track, through a pleasant

farming-country, but shows you few points where you will care

to spend much time in sight-seeing. If you are wise, you will

elect, as we did, to be a through passenger. It terminates at

Bethlehem, and is there met by two roads which run side  by side up the narrow

valley of the Lehigh, and open to the traveler one of the most

delightful short-trip routes in America. Fifty years ago the valley

was a wilderness, with one narrow wagon-road crawling at the base

of the hills beside a mountain-torrent which defied all attempts

to navigate it. Now, the mountain-walls make room for two railroads

and a canal, but the tawny waters of the stream are nearly as

free as ever. Here and there, indeed, a curb restrains them, and

once an elaborate system of dams and locks tamed the wild river,

and made it from Mauch Chunk to White Haven a succession of deep

and tranquil pools. But one day in 1862 the waters rose in their

might. Every dam was broken, every restraint swept away, and from

White Haven to Mauch Chunk the stream ran free once more. The

memory of that fearful day is still fresh in the minds of the

dwellers in the valley, and the bed of the torrent is still strewn

with the wrecks that went down before its wrath. The Lehigh Company,

who had planned and constructed this magnificent system of slackwater

navigation, looked on in silent dismay and saw the labor of years

vanish in a moment, shook their heads, and proceeded to build

a railroad. After that day's experience they felt as if they could

never trust the river again. by side up the narrow

valley of the Lehigh, and open to the traveler one of the most

delightful short-trip routes in America. Fifty years ago the valley

was a wilderness, with one narrow wagon-road crawling at the base

of the hills beside a mountain-torrent which defied all attempts

to navigate it. Now, the mountain-walls make room for two railroads

and a canal, but the tawny waters of the stream are nearly as

free as ever. Here and there, indeed, a curb restrains them, and

once an elaborate system of dams and locks tamed the wild river,

and made it from Mauch Chunk to White Haven a succession of deep

and tranquil pools. But one day in 1862 the waters rose in their

might. Every dam was broken, every restraint swept away, and from

White Haven to Mauch Chunk the stream ran free once more. The

memory of that fearful day is still fresh in the minds of the

dwellers in the valley, and the bed of the torrent is still strewn

with the wrecks that went down before its wrath. The Lehigh Company,

who had planned and constructed this magnificent system of slackwater

navigation, looked on in silent dismay and saw the labor of years

vanish in a moment, shook their heads, and proceeded to build

a railroad. After that day's experience they felt as if they could

never trust the river again.

I have said that our trip was partly for business and partly for

pleasure. Had it been wholly for pleasure, we should have waited

for the 9:45 train from the North Penn depot which would have

taken us over the Lehigh and Susquehanna Road. As it was, we rose

at an uncomfortably early hour and took the eight o'clock train,

which connects with the Lehigh Valley Road. In either case, however,

the discomfort ends with the traveler's arrival at the depot.

Thence comfortable cars take him to Bethlehem, and from Bethlehem

northward, over either road, through the picturesque Lehigh Gap

and up the mountain-valley.

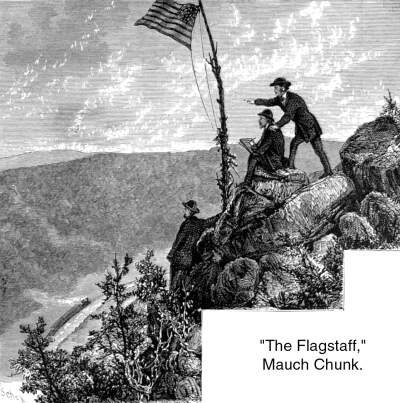

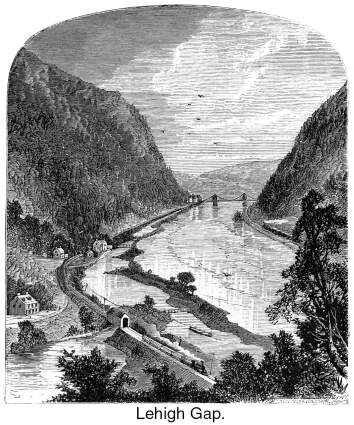

Soon after

leaving Bethlehem the mountains approach the bed of the stream,

and at the Gap fling themselves directly in its path, leaving

it no resource but to go through them; which it has accordingly

done, cleaving the mountain from summit to base in its efforts

to escape. Soon after

leaving Bethlehem the mountains approach the bed of the stream,

and at the Gap fling themselves directly in its path, leaving

it no resource but to go through them; which it has accordingly

done, cleaving the mountain from summit to base in its efforts

to escape.

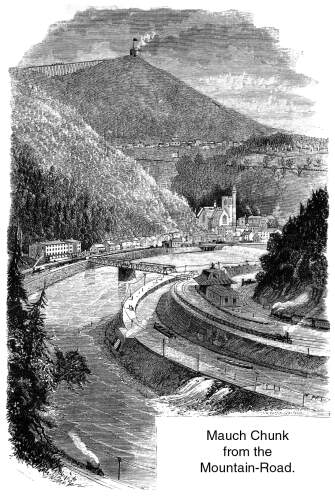

But it is not until the vicinity of Mauch Chunk is reached

that the peculiar features of the Lehigh Valley appear in perfection.

From here northward it is little better than a canyon enclosed

between high mountain-walls, at whose bases the narrow stream

tumbles and foams, its waters now displaying the rich amber hue

which they have distilled from the roots and plants in the swamps

around their source, now white from their encounter with rock

or fall. Huge rocks hang directly overhead, and threaten to fall

at any moment upon the trains which constantly roll beneath; branches

wave and flowers bloom on the hillside, so close to the track

of the railroad that the passenger can almost reach them without

leaving his seat; here and there a miniature waterfall tumbles

over the brow of a mountain, and glances, a ribbon of foam and

spray, to the river at its foot; and at frequent intervals ravines

cut in the mountain-side present a confusion of rocks and wood

and water to the eye of the traveler as he flashes by. Traced

back a little way from their mouths, these glens often show a

wealth of beauty, a succession of snowy cascades, transparent

pools and romantic nooks which are an ever fresh surprise to the

explorer.

At White Haven both roads leave the valley, cross the intervening

mountain and descend into the Wyoming Valley—a land celebrated

in song and story, a land famous alike for its beauty and its

history. This, by the way, to fill up the gap, as it were, between

our departure from Philadelphia and our arrival at Mauch Chunk.

Here we were to change cars and run up the Nesquehoning Road to

the High Bridge. Half the proposed change was accomplished successfully.

We left the Lehigh Valley train, but while we waited for the Nesquehoning

train to draw up in front of the Mansion House, it came and went,

and we missed it.

"No matter,"

said the Railroad-man. "We'll catch it at the depot."

Now the depot was a quarter of a mile away, and the train stopped

there about a quarter of a minute. Evidently, there was no time

to be lost. We struck into a lively run, the best man ahead, while

the Mauch Chunkites looked out from four tiers of houses to see

the procession. We made good time in that quarter-mile heat, but

the track was curved and the train had the inside. So we missed

it. It was the second time I had chased a railroad-train, and

I missed the first one. I begin to believe I can't catch one. "No matter,"

said the Railroad-man. "We'll catch it at the depot."

Now the depot was a quarter of a mile away, and the train stopped

there about a quarter of a minute. Evidently, there was no time

to be lost. We struck into a lively run, the best man ahead, while

the Mauch Chunkites looked out from four tiers of houses to see

the procession. We made good time in that quarter-mile heat, but

the track was curved and the train had the inside. So we missed

it. It was the second time I had chased a railroad-train, and

I missed the first one. I begin to believe I can't catch one.

When we arrived at the depot the Artist and I said we had had

enough railroading for one day. We were surprised to find what

an appetite our exercise had developed, and proposed to adjourn

for dinner; but the Railroad-man wouldn't listen to us. He was

bound for the Nesquehoning, train or no train, and he went. In

less than five minutes he had impressed a freight train, loaded

us on it, and we were off. The conductor warned us to "Look

out for sparks. She throws cinders pretty lively, sometimes;"

and we soon began to perceive the value of his admonition. "She"—meaning

the locomotive—uttered a preliminary whistle, and then began

to snort like a porpoise with the whooping-cough, while the atmosphere

suddenly put on an appearance as if a burnt cork factory was being

distributed through it in fine particles. The first rod we traveled

we turned our backs on the engine; the second we turned up our

coat-collars; the third we crawled behind a pile of sills on an

open truck—the same upon which we had at first been seated.

But all would not do. The cinders continued to find us. They flew

into our mouths and ears and eyes and noses, and down our backs

and up under our hats; and wherever they went they burned; and

when we presently struck a heavy grade they came faster than ever.

Human nature could not stand it. "See here," said we,

"this won't do. We shall all look like convalescent smallpox

patients in five minutes more. Let's get out of this."

"Easier said than done. There isn't a covered car on the

train, and we're running too fast to jump off. Besides, we're

bound to see the bridge if we die for it."

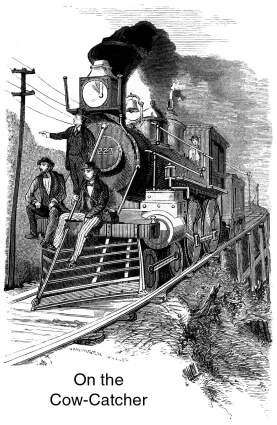

"Let's get out on the cow-catcher."

"Lucky thought! But have you ever tried it ?"

"Often. No cinders there, no smoke, no dust; but a pleasant

breeze that will be delightful this warm day; and then you're

always the first to arrive."

"Enough! Lead on!"

We went forward

and interviewed the engineer. That dignitary was disposed to accommodate

us, but recommended "a bright lookout for cows." We went forward

and interviewed the engineer. That dignitary was disposed to accommodate

us, but recommended "a bright lookout for cows."

"Cows! up here in the woods!"

"Lots of 'em. Run over one every once in a while."

"All right! If we see a cow we'll let you know."

We wanted to show that engineer that we were brave men. We never

had been afraid of cows, and were not going to be now. Besides,

we were half inclined to believe he was hoaxing us. It didn't

look like a good cow-country; and even if it was, and the cows

were thick as grasshoppers, it was his business to steer clear

of them. That's what he was there for.

So we stepped lightly out on the footboard, took a hard grip

on the handrail and cautiously made our way along the iron monster's

side, placed a foot on the steam-chest, swung over on the bumper,

and there we were. It was a glorious ride. The broad platform

on the front of the engine furnished excellent seats, albeit they

were a trifle hard, and the bars of the "pilot," as

railroad-men term the article known to us as the cow-catcher,

seemed made on purpose for footrests. We could feel every throb

of the engine's fiery heart, every gasp of its rapid breathing:

every joint of the rails sounded as we passed like the tramp of

an iron hoof, and the huge machine trembled in every fibre as

it flew along like a living creature urged to its utmost speed.

The air was balmy, the discomforts of the train all behind us,

and before us just enough prospect of danger to add a pleasant

thrill of excitement to the attractions of the ride. The sharp

nose of the "pilot" skimmed along just above the track,

threatening every instant to bury itself in the next stone or

sill that showed its head above the dead level, and tumble us

all into the ditch, but always clearing the obstacle by an inch

or two, and running on without a jar. For pleasant railroad traveling

in warm weather I must recommend the cow-catcher. There's nothing

like it. The only drawback is that it is risky. The cars may run

off the track and smash all to bits, and you may crawl out from

under the ruins perfectly uninjured. I even know an engineer whose

engine took him down an embankment, and literally, and without

any fiction about it, rolled over him twice; and he picked

himself up as sound as you are, got another engine and train and

went ahead, for it was wartime and he was conveying important

orders. But a cow-catcher never does things by halves. You ride

safely or you are killed instantly: one or the other is bound

to happen.

In our case it

was the former. We rushed along in perfect safety, and though

the predicted cow appeared in due time, and stood defiantly on

the track for a while, she changed her mind before we came within

striking-distance and walked quietly away. In our case it

was the former. We rushed along in perfect safety, and though

the predicted cow appeared in due time, and stood defiantly on

the track for a while, she changed her mind before we came within

striking-distance and walked quietly away.

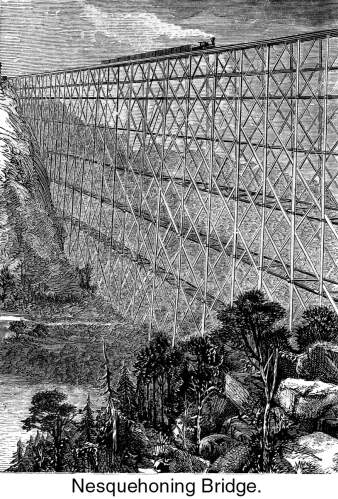

The Nesquehoning bridge has great local celebrity as the highest

bridge in the country. It is flung from one mountain to another

at an elevation of one hundred and sixty-eight feet above the

Little Schuylkill, an insignificant stream flowing through a deep

gorge. Its length is eleven hundred feet, and the view each way

from its platform is one worth going all the way to see. The Railroad-man

inspected it. The Artist made what he called a "rough sketch"

of it—it took him ten minutes, and looked like a perspective

view of a centipede—and then the Catawissa Express came along,

and carried us back to Mauch Chunk and a late dinner.

It was the first day out, and we didn't care how hard we traveled.

We learned better afterward, but now, when the Railroad-man said,

"Shall we go over the Switchback this afternoon?" the

question was carried unanimously in the affirmative.

So he sent out and ordered a "special train." That

sounds magnificent, does it not? We thought so, and we felt like

millionaires as we walked into the Mansion House and ordered our

late dinner.

Dinner over, we walked leisurely to the train—a stroll

which involved the ascent of what, in any other part of the country,

would be called "pretty considerable of a hill." The

Gravity Road nominally runs to the foot of Mount Pisgah, but the

road gives out some time before the gravity does. Ordinary tourists

make the intervening distance in coaches—we aristocrats did

it on foot.

The special

train was in waiting when we arrived. It consisted of one flat

car, half the size of a billiard-table, with seats for ten, and

no top. A pretty little affair, what there was of it, but it scarcely

came up to our expectations of a special train. The special

train was in waiting when we arrived. It consisted of one flat

car, half the size of a billiard-table, with seats for ten, and

no top. A pretty little affair, what there was of it, but it scarcely

came up to our expectations of a special train.

"This is the superintendent's car. He has loaned it to

us as a special favor. The covered cars will not suit our purpose

as well as this."

Then we took heart again, and got on board, but the Artist

looked suspiciously at the track before us, and asked questions

enough to fill the Shorter Catechism.

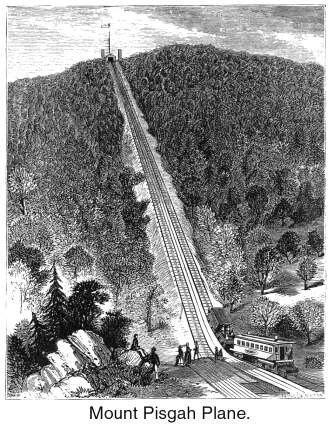

"What's that?"

"Mount Pisgah Plane, two thousand three hundred and twenty-two

feet long. You are now two hundred and fifteen feet above the

river, and the river here is five hundred and twenty feet above

tide-water; and when you get to the top of the plane you will

be six hundred and sixty-four feet higher still. That iron band

hauls up the empty cars on their way back to the mines. It is

attached to a 'safety-truck,' which is down in that hole at the

foot of the plane. It goes down there, so that the cars can pass

over and get in front of it. There it goes now. You see it pushes

ten or a dozen cars before it up the plane. The wire rope which

it drags after it runs over a drum-wheel at the foot of the plane—there

it is, that uneasy thing which is always trying to haul a cart-load

of old iron up the hill, and never succeeding—and the other

end of the rope pulls down the safety-truck on the other track.

You see that long arm which projects from the side of the safety-truck

and counts the teeth of that iron thingumbob between the tracks

with such monotonous regularity?

That's the 'safety'

part of the arrangement. It is expected to hold the train right

there in case the bands happen to break.—Oh, bless you, yes!

They break every now and then. Never broke yet with a passenger-train,

though—we don't load 'em heavy enough—but if they did

the ratchet would hold the cars till the bands were spliced again.

This is the last season for coal-trains. We are sending a good

deal of our coal through the Nesquehoning tunnel now, and pretty

soon shall send it all that way; and then this road will be used

for passenger business exclusively." That's the 'safety'

part of the arrangement. It is expected to hold the train right

there in case the bands happen to break.—Oh, bless you, yes!

They break every now and then. Never broke yet with a passenger-train,

though—we don't load 'em heavy enough—but if they did

the ratchet would hold the cars till the bands were spliced again.

This is the last season for coal-trains. We are sending a good

deal of our coal through the Nesquehoning tunnel now, and pretty

soon shall send it all that way; and then this road will be used

for passenger business exclusively."

This connected discourse is the substance of answers to the

Artist's catechism. The questions would only take up room to no

purpose, and, besides, I like to dispense information in solid

chunks.

By the time this exercise was concluded we were on our way

up the plane. Our ten or twelve hundred pounds were a mere bagatelle

to the big engines accustomed to drawing up fifteen or twenty

tons at a time, and we glided lightly and safely to the top, where

the catechetical instruction was resumed.

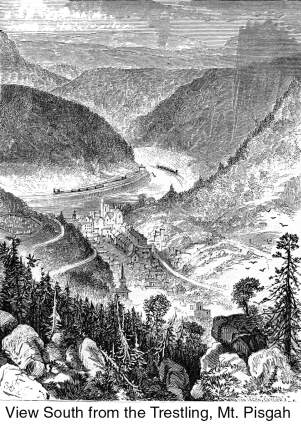

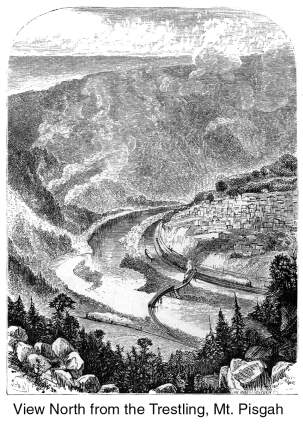

"Angle of plane is about twenty degrees. That is Upper

Mauch Chunk on the plateau to the right of the plane, and across

the river you see East Mauch Chunk. Better location than the original

settlement—after you get up to it. No trouble about the drainage,

eh? Old town was started in 1818. First child—living still,

I believe—was Nicholas Brink, born in 1820, and was named

after everybody in the settlement. Had names enough for all his

descendants to the third generation. It's getting late. All aboard!

"—and he hurried us away without giving us half enough

time to enjoy the magnificent views from the trestling at the

top of the plane. We must keep moving if we would do the whole

twenty-five miles of Gravity Road between that time and six o'clock,

when the planes would cease working. So we set out without further

delay.

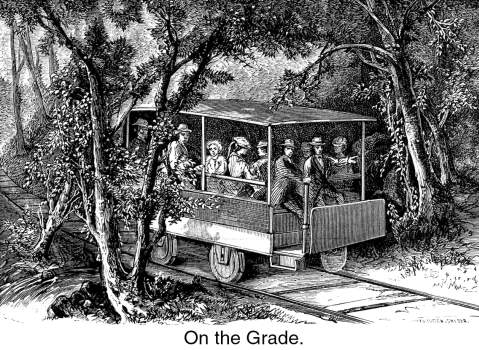

The Railroad-man

sat in front and held the brake, a lever by which he could slow

or stop the truck at will; but he seldom had the will to do it.

As a general thing, he let it run. The grade from Mount Pisgah

to the foot of Mount Jefferson is sixty feet to the mile—just

enough to propel a light car at a moderate speed. The ride was

through the woods all the way—a pleasant, breezy, cool and

clean run with no danger in it that could not be avoided by a

judicious use of the brake. At Mount Jefferson we were hauled

up another plane, two thousand and seventy feet long, and four

hundred and sixty-two feet high; and one mile from its top we

ran into Summit Hill. The Railroad-man

sat in front and held the brake, a lever by which he could slow

or stop the truck at will; but he seldom had the will to do it.

As a general thing, he let it run. The grade from Mount Pisgah

to the foot of Mount Jefferson is sixty feet to the mile—just

enough to propel a light car at a moderate speed. The ride was

through the woods all the way—a pleasant, breezy, cool and

clean run with no danger in it that could not be avoided by a

judicious use of the brake. At Mount Jefferson we were hauled

up another plane, two thousand and seventy feet long, and four

hundred and sixty-two feet high; and one mile from its top we

ran into Summit Hill.

Then we ran down into Panther Creek Valley, and traversed the

whole course of the Switchback Road, returning late in the evening,

and whizzing down the nine miles between Summit Hill and Mauch

Chunk in nineteen minutes.

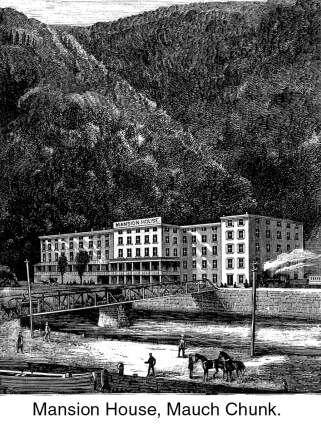

Mine host Booth, at the Mansion House, gave us, as he gives

everybody, an excellent supper and splendid beds, and we made

his house our head-quarters during our stay. We sat on the piazza

after supper and smoked cigars and chatted, and watched the fires

on the mountains, which drew bands of flame all around the town,

and counted the long coal-trains that wound among the hills on

either side of the valley; and when we were tired of this we went

to bed, and were lulled to sleep by the plash and drowsy tumult

of the river under our windows.

We made another

trip over the Switchback a few days after, and as this is not

a consecutive narrative I may as well tell the whole story here,

and have done with it. We made another

trip over the Switchback a few days after, and as this is not

a consecutive narrative I may as well tell the whole story here,

and have done with it.

To begin at the beginning: "The Switchback" is not

a switchback at all, in the technical sense of the word, and has

not been for years. Originally, there were several switchbacks

along the "Gravity Railroad," which is the proper name

for the line under consideration, and they were operated thus:

the cars, running smoothly on a down grade, would reach a point

where they suddenly found themselves going up hill at such a rate

that they were quickly compelled to stop. Then the attraction

of gravitation, constantly drawing them down hill, would cause

them to reverse their direction and run back; but when they again

reached the place where the grade changed, a switch, worked by

a spring, threw them on another track, and they continued their

journey down the mountain in a direction contrary to that in which

they had been running before they came to  the switchback. The next interruption

would send them in the original direction; and in this zigzag

fashion they accomplished the descent into Panther Creek Valley.

Later and better engineering has changed the switchbacks into

curves, and the descent from Summit Hill to the mines is made

without interruption; but the name, which at first was local and

applied to a particular point, gradually spread until it included

the entire road. the switchback. The next interruption

would send them in the original direction; and in this zigzag

fashion they accomplished the descent into Panther Creek Valley.

Later and better engineering has changed the switchbacks into

curves, and the descent from Summit Hill to the mines is made

without interruption; but the name, which at first was local and

applied to a particular point, gradually spread until it included

the entire road.

And now, having done away with the switchback business, we

will adhere to the proper title, and call our mountain path the

Gravity Road.

This is next to the oldest railroad in the United States. Its

only predecessor was a road three miles long connected with the

Quincy stone-quarries in Massachusetts. That was built in the

fall of I826—this went into operation in May, 1827.

At first the road extended only from Summit Hill to Mauch Chunk.

There was no return track, and consequently no planes, the empty

cars being hauled back to the mines by gangs of mules, which,

in turn, were transported to Mauch Chunk in cars designed expressly

for their use—a ride which they learned to value so much

that no amount of persuasion could induce them to make the journey

on foot. Subsequently, the Panther Creek mines were opened, the

Switchback proper made to reach them, and planes built to assist

gravitation in transporting the cars.

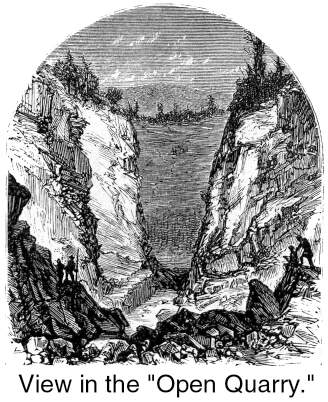

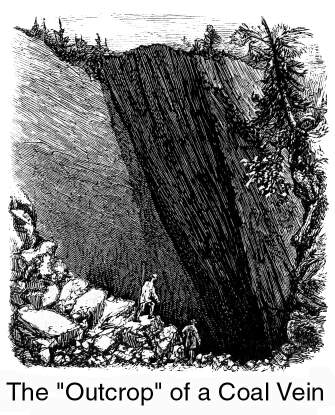

We visited

the spot where, in 1791, Philip Ginther stumbled over a fortune

that was not for him, and where the famous "Open Quarry"

was afterward worked. A part of the wide excavation has been filled

up with the refuse from other workings, but enough remains to

give the visitor an idea of the immense mass of coal originally

deposited here. A better idea of the disposition of the strata

can be gained, however, at an adjoining opening, where the outcrop

of the vein has fallen into the subterranean workings. The solid

mass of coal is here seen just as the last earthquake left it—a

mass of pure, glittering fuel, forty feet or more in thickness

(we did not measure it, for reasons apparent in the illustration),

and running, at a steep pitch, far down into the bowels of the

earth. We visited

the spot where, in 1791, Philip Ginther stumbled over a fortune

that was not for him, and where the famous "Open Quarry"

was afterward worked. A part of the wide excavation has been filled

up with the refuse from other workings, but enough remains to

give the visitor an idea of the immense mass of coal originally

deposited here. A better idea of the disposition of the strata

can be gained, however, at an adjoining opening, where the outcrop

of the vein has fallen into the subterranean workings. The solid

mass of coal is here seen just as the last earthquake left it—a

mass of pure, glittering fuel, forty feet or more in thickness

(we did not measure it, for reasons apparent in the illustration),

and running, at a steep pitch, far down into the bowels of the

earth.

"This fall," said the Railroad-man, "carried

part of the track running into 'No. 2' down with it, and we had

no end of bother with it before we got it filled up again and

the track relaid. That hole you see at the bottom is some six

hundred feet deep, and dumping gravel into it was almost like

trying to fill up the bottomless pit itself."

"Why didn't you go round it?"

"Couldn't. You see those alps of coal-dirt all around

us. We should have had to move those at any rate, and so we just

moved a few of them in here—sent them back where they came

from, as it were—and so at last the thing was done."

"Does

that thing happen often?" "Does

that thing happen often?"

"What thing?"

"Losing your track suddenly in that fashion. Because,

if it is, we prefer some other road. We're not ready to start

for China by the underground route just yet."

"Don't alarm yourselves. We keep a lookout for breakdowns,

and know just where the ground is weak. You will go through safely

enough this trip, and hereafter, if you're fearful, you can confine

yourselves to the regular passenger-route from Mauch Chunk to

Summit Hill and return. There's no danger there."

So we were comforted, and went on to "No. 2," which

is one of the oldest collieries in the region; and enjoyed the

fine view of Panther Creek Valley which is seen from the end of

its dirt-bank; and looked down the slope, which they told us was

fifteen hundred feet deep (we didn't measure it); and then we

took a look at Summit Hill, which is dirty and uninteresting in

itself, like all mining towns; and then we mounted our truck again

and shot down a fearfully steep grade into Panther Creek Valley.

Here one of the first things we were shown was a burning mine,

but it was a poor affair, recently kindled and on the verge of

being extinguished. The only noticeable thing about it was the

process of putting out the fire by forcing carbonic acid gas into

the mine, and that we did not see. There is another mine at Summit

Hill, which has been burning for thirty years, and is likely to

burn for thirty more: that, now, is something to brag of. A greater

curiosity was the entrance to the Nesquehoning tunnel, four  thousand feet long,

a work completed last winter, and one which at one fell swoop

claps an extinguisher on the Gravity Road with all its complicated

machinery. Hereafter, all the coal of this region, instead of

careering wildly over the mountains, drawn by viewless steeds

and enveloped in an atmosphere of romance, will be drawn by a

commonplace locomotive upon a commonplace track through this tunnel

and down the Nesquehoning Road, to Mauch Chunk and a market. But

the Gravity Road will remain for the present, and passenger-trains

will still run on it for the accommodation of those who wish to

enjoy its exhilarating ride, its grand scenery and its many points

of interest. thousand feet long,

a work completed last winter, and one which at one fell swoop

claps an extinguisher on the Gravity Road with all its complicated

machinery. Hereafter, all the coal of this region, instead of

careering wildly over the mountains, drawn by viewless steeds

and enveloped in an atmosphere of romance, will be drawn by a

commonplace locomotive upon a commonplace track through this tunnel

and down the Nesquehoning Road, to Mauch Chunk and a market. But

the Gravity Road will remain for the present, and passenger-trains

will still run on it for the accommodation of those who wish to

enjoy its exhilarating ride, its grand scenery and its many points

of interest.

Before our return home, the Railroad-man proposed that we should

spend a day at Upper Lehigh.

"Where's that?" shouted the chorus.

"Up among the mountains back of White Haven. New place,

just chopped out of the woods: splendid scenery—rocks, ravines,

cascades, good hotel—"

"That'll do! When do we start?"

The Railroad-man named a time for rising, somewhere among "the

wee, sma' hours;" and with the time came Jim to wake us.

Jim is one

of the institutions of Mauch Chunk. He is a colored citizen, the

porter of the Mansion House, and his duties are those heterogeneous

ones which pertain to porters generally, and to porters in country

hotels particularly. To the traveler entering the town by the

Lehigh and Susquehanna Road the first sight of Mauch Chunk is

Jim standing in front of the hotel and shouting, "Twenty

minutes for dinner! Step right this way, gemmen." And when

the twenty minutes have expired, Jim is seen vibrating like an

ebony shuttlecock between the train and the hotel, gesticulating

excitedly and urging the travelers to an immediate departure.

"Time's up, gemmen! Train's a-goin'. All aboard!" Then

to the conductor," Hi! holdon, dar! Heah's a couple o' ladies

yit." This duty fulfilled, Jim retires into his sanctum,

where he may be seen at any time between-trains, blacking boots

and lecturing on politics to chance hearers. Jim is one

of the institutions of Mauch Chunk. He is a colored citizen, the

porter of the Mansion House, and his duties are those heterogeneous

ones which pertain to porters generally, and to porters in country

hotels particularly. To the traveler entering the town by the

Lehigh and Susquehanna Road the first sight of Mauch Chunk is

Jim standing in front of the hotel and shouting, "Twenty

minutes for dinner! Step right this way, gemmen." And when

the twenty minutes have expired, Jim is seen vibrating like an

ebony shuttlecock between the train and the hotel, gesticulating

excitedly and urging the travelers to an immediate departure.

"Time's up, gemmen! Train's a-goin'. All aboard!" Then

to the conductor," Hi! holdon, dar! Heah's a couple o' ladies

yit." This duty fulfilled, Jim retires into his sanctum,

where he may be seen at any time between-trains, blacking boots

and lecturing on politics to chance hearers.

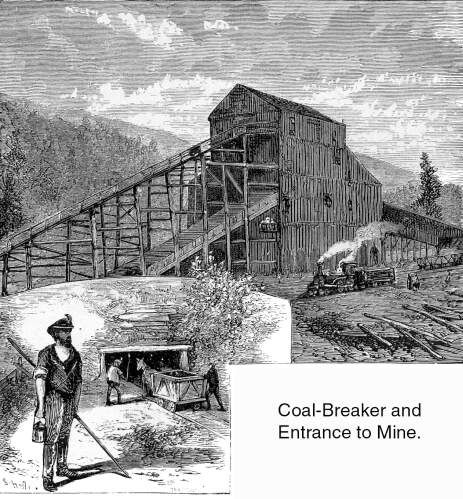

Well, Jim called us in the early morning—and morning among

the Lehigh Mountains is worth getting up to see. We ate our breakfast,

went to White Haven, changed cars, and rode up the Nescopec Railroad

to Upper Lehigh. The Nescopec Road is nine miles long, and runs

nothing but through trains, by reason of there being no way stations

on the route. At the end of it is a coal-breaker, one of the best

in the anthracite region, shipping five thousand tons of coal

a week; a good hotel—the Railroad-man was right about that;

a row of miners' houses and—woods. We walked about half a

mile along a wood-road, struck into a footpath, followed it a

hundred yards or so, and without warning, walked out on a flat

rock from which we could at first see nothing but fog, up, down

or around. It was a misty morning, but we made out to understand

that we were on the verge of a precipice which fell sheer down

into a tremendous abyss; and when the fog lifted, as it did about

noon, we looked out upon miles and miles of valleys partly cleared,

but principally covered with the primeval forest.

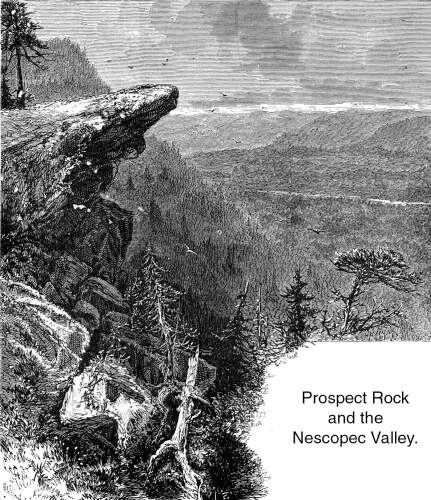

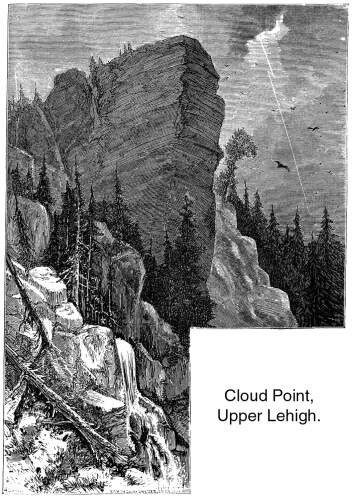

We were on

Prospect Rock then. Presently our guide took us, by a round about

way, to Cloud Point, a corresponding projection, on the other

side of the glen, and here a still wider view, another yet the

same, lay before us. We gazed on the beautiful landscape until

we thought we could afford to leave it for a while, and then descended

into Glen Thomas, so called in honor of David Thomas, the pioneer

of the iron trade on the Lehigh. It was the first of May, but

we found here miniature glaciers formed by the water falling over

the rocks, the ice three feet and more in thickness, and so solid

that a pistol-ball fired at it pointblank rebounded as from a

rock, while not a hundred yards away May flowers were blooming

in fragrant abundance. We were on

Prospect Rock then. Presently our guide took us, by a round about

way, to Cloud Point, a corresponding projection, on the other

side of the glen, and here a still wider view, another yet the

same, lay before us. We gazed on the beautiful landscape until

we thought we could afford to leave it for a while, and then descended

into Glen Thomas, so called in honor of David Thomas, the pioneer

of the iron trade on the Lehigh. It was the first of May, but

we found here miniature glaciers formed by the water falling over

the rocks, the ice three feet and more in thickness, and so solid

that a pistol-ball fired at it pointblank rebounded as from a

rock, while not a hundred yards away May flowers were blooming

in fragrant abundance.

We spent the whole day in rambling over the rocks and through

the glen, and at evening took the return train to White Haven,

the Artist and the Photographer—who had joined us at Mauch

Chunk—vowing to return soon and often.

Another long-to-be-remembered excursion was to Moore's Ravine,

a wrinkle in the mountain-side two miles, above Mauch Chunk, filled

with tall hemlocks, and at their feet a stream tumbling, in a

continual succession of cascades, from the top of a mountain to

its base. In little more than a quarter of a mile the stream makes

a sheer descent of at least three hundred feet, distributing it

in twenty-one cascades and waterfalls. Two of these, which are

so close together as almost to make one continuous fall and are

named Moore's Falls, are over a hundred feet in total height.

The others are smaller, but no less beautiful, while the limpid

pools of still water among them are by no means the least attractions

of the place.

But the glen is as wild as

it is picturesque, and to see it requires a good supply of both muscle and perseverance.

It has never been "improved," even to the extent of a footpath, and

the visitor might fancy himself the first that had ever entered it if it were

not for the evidences to the contrary borne by prominent places where a couple

of idiots scrawled their names in white paint. I hope I may be forgiven for

wishing they had tumbled over the highest fall. But the glen is as wild as

it is picturesque, and to see it requires a good supply of both muscle and perseverance.

It has never been "improved," even to the extent of a footpath, and

the visitor might fancy himself the first that had ever entered it if it were

not for the evidences to the contrary borne by prominent places where a couple

of idiots scrawled their names in white paint. I hope I may be forgiven for

wishing they had tumbled over the highest fall.

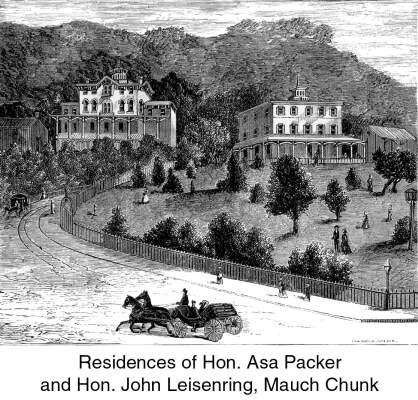

But the growing length of this article warns me to "cut it short."

I may not tell of our carriage-ride into the Mahoning Valley, with its pleasant

views and drives; nor of mountain-climbing at Mauch Chunk; nor of the flying

visit we paid to Wilkesbarre and Scranton in the beautiful Wyoming Valley; nor

of the day we spent in the pleasant Moravian town of Bethlehem, where we put

up at an ancient hostelrie which was called the "Sun Tavern" a hundred

and odd years ago, and which, under the more modern title of the "Sun Hotel,"

is now, as it was then, one of the best inns in the interior of the State. All

these things must remain untold, but the reader can enjoy them all for himself

at small cost of time or money. He can see the Lehigh Valley, Switchback and

all, in a single day, returning to Philadelphia the same evening, or he can

spend a whole summer in exploring its woods and mountains.

His best plan, however, for a short trip, is to leave Philadelphia or New York

on one of the early trains, timing himself so that he can be at the Mansion

House, Mauch Chunk, in time for dinner. This is the best hotel in the valley

above Allentown, and for that reason he will do well to make it his stopping-place

for the night. After dinner he will have plenty of time to go over the Gravity

Road and return in time for supper. Next morning an early train will take him

to White Haven, where he can change cars and run up the  Nescopec

Road to Upper Lehigh, which he will reach about noon. Here he will have ample

time to dine and explore Glen Thomas, but not to see all the fine views from

this singular mountain-top if he would return by the afternoon train. This train

makes connections for both Philadelphia and New York, either of which can be

reached the same evening; but a third day can be profitably spent at Upper Lehigh,

and part of a fourth in exploring Moore's Ravine—to me one of the greatest

attractions about Mauch Chunk, but, unfortunately, accessible from that place

only on foot. It demands a hard walk and a hard climb, but offers in return

a scene of wild and rugged magnificence which in all my mountain-climbing I

have never seen excelled. Nescopec

Road to Upper Lehigh, which he will reach about noon. Here he will have ample

time to dine and explore Glen Thomas, but not to see all the fine views from

this singular mountain-top if he would return by the afternoon train. This train

makes connections for both Philadelphia and New York, either of which can be

reached the same evening; but a third day can be profitably spent at Upper Lehigh,

and part of a fourth in exploring Moore's Ravine—to me one of the greatest

attractions about Mauch Chunk, but, unfortunately, accessible from that place

only on foot. It demands a hard walk and a hard climb, but offers in return

a scene of wild and rugged magnificence which in all my mountain-climbing I

have never seen excelled.

Stories

Page | Contents Page Stories

Page | Contents Page

|