|

|

|

|

Chapter I

The Gröt Vly's Victime

From "The Land Of Rip Van Winkle" (1884)

By A.E.P. Searling |

|

George Hall's House |

It was the custom of our English cousins, in the early days of revolt and trouble with the colonies, to use with unstinted zeal the hate and cruelty of the red man as weapons against their rebellious subjects. If the atmosphere be permeated with a subtle magnetic fluid, as some spiritualists assert, on which passing events are photographed in gesture and grouping of figures, then, to him who has the " second sight," the valleys of the Hudson and Mohawk rivers unroll one long panorama of human agony. Rapine, arson, and murder marshal their forces in the ghostly procession. |

|

Wild arms are raised to heaven in vain appeals for help. Women and children are fleeing from demons in war-paint and feathers who are in hot pursuit, while the smoke from burning barns and homesteads seems to rise like incense to the heathen gods of War and Death. Give voice to this phantasmagoria of horrors, and what a wail of agony goes up in accusation! Who was to blame?

Perhaps the captivities were a degree worse than immediate murder, for in the one case there ensued the long march through the great forests and across mountains and rivers to Canada, where, if the wretched one lived to reach that destination, there awaited him impressment into the British service, or an imprisonment whose horrors were equal to his previous tortures by the savages; in the other case the tomahawk was at least a merciful shortening of the death.

About two miles west of Catskill lived in those troubled days the Dutch family of Schermerhorns. One son had married a daughter of Mr. Scrope, who lived on Roundtop Mountain . Another son, Frederic, was one day sent to the mountain where his brother had taken up his abode with his wife's people to obtain his services in helping to get the Schermerhorn sheep driven down from their mountain pasture. Arrived at his destination, and greatly wearied from his long day's journey, he soon retired to rest. In the early morning he was aroused by the screams of his sister-in-law, who was alarmed by the appearance of some Indians who were approaching the house. Long afterward, in telling the story to his children Frederic used to recall how his dog had howled when he left home the day before, and then he would add: "Mine kindern, petter stay to home yen to dog howls!"

Drawing on his clothes quickly he ran down stairs to find the family in great alarm. Mr. Scrope had been at work in the fields but was coming back to the house now, having seen the approach of the savages. Meanwhile the warriors seemed friendly enough with their "How-do's" and inquiries for Bastyon, a son of the house who was then absent in Saugerties. It was afterward thought that their object in coming was to seize and kill this Bastyon, who had once served them a mean trick in stealing from them some hatchets and knives. Finding their inquiries for the delinquent to be in vain, they concluded to satisfy their grudge in some other way, and so began plundering the house, thereby trying the frugal soul of Vrouw Scrope, who wept and fumed to no good purpose. One brave, possessed of unusual discernment spied the linen-chest in the corner, and breaking it open seized a long uncut piece of the home-spun, and trailing it proudly behind him boasted: "Make Indian good shirt! This was more than could be endured by the woman who had spun and woven with her own hands, and making a dash at the impious red man, Vrouw Scrope shouted: "You no hef dat! dat Bastyon's piece!" |

Dog's Hole, Palenville |

Old Mr. Scrope coming in at this juncture was filled with horror at his wife's rashness and cried: “Vor Cot's sake, let dem hef vat dey vill, you lose your bet yet! But the warning proved of no avail, for what was a Dutch vrouw's life worth to her despoiled of her store of linen, and the Indian soon settled the point by killing the brave woman and laying her husband dead beside her. The daughter, while this scene was being enacted and all the Indians intent upon the issue, quickly snatched her baby from the bed, and gathering her three other children together, fled with them through a back door and hid with them in a field of rye.

The Indians soon fired the house and left, bearing with them much plunder, including, no doubt, " Bastyon's piece," so valiantly defended, and the boy Schermerhorn as a captive. |

|

At their departure the terrified young mother crept from her hiding-place, and with her little ones followed the Kiskatom creek to the house of Mr. Timmerman, five miles away. Meanwhile the husband, Schermerhorn, returned from his two days' journey to mill, and found his home in ashes, with no trace of its inmates but a few charred bones. Half crazed with grief at the possible fate of his family, he at last found his wife and children and learned from them the death of his parents and the captivity of his younger brother. He quickly formed a party of men and went in pursuit of the savages, but as well pursue the east wind, for their path over the mountains was as trackless.

The story of the long march, the days of hunger and parching thirst, through the summer heat, the weary feet bleeding and sore, and yet the lips not daring to complain lest the tomahawk should quickly settle all, makes a sad history indeed.

One night, encamped near Schoharie, the Indians drew forth the scalps of the murdered Scropes and proceeded to dry them on little hoops before the fire. One of the men, making a third hoop, suddenly sprung up with a savage yell and made a dash at Schermerhorn, who now stood transfixed with fright. Seizing the boy by the hair, he made passes at him with the scalping-knife, when the poor youth could endure no more and fell fainting with terror and exhaustion at his captor's feet. The other Indians, immensely diverted by this witty sally on the part of their companion, rolled over and over on the ground screaming with laughter. On another occasion the lad was made to "run the gauntlet," a hideous custom rigidly adhered to by all Indians bearing away captives. When approaching a settlement of friendly savages, the prisoner was stripped naked and compelled to pass between two lines of the villagers, whose custom was to shower on the victim all kinds of torments in the shape of blows, pricks, and cuts from sharp knives. Lucky was the man who came through the ordeal alive.

At Fort Niagara - Ne-a-gaa-ra the Indians called it always Schermerhorn's captors received eight dollars apiece for the scalps they brought, that being the usual bounty paid by the British for such rebel headgear, and forty dollars for their prisoner, who was forthwith impressed into the army. From that time he saw no more of home or friends till the year after the close of the war, when he wandered back and at last found his parents living in Hudson .

Along the line of the Hudson River, about half a mile from its west bank, runs a line of abruptly rising hills, called "The Collaberg." Near Catskill they dip suddenly to the westward into a narrow valley, across which hills rise again in higher crests toward the mountains. Where Kaaterskill creek comes winding down from its birthplace in the Catskills, and crosses this lovely little valley, there spreads out a plateau of fertile farm-land. There, in a sheltered spot, by a glassy pool, where willows dip and swing to their long reflections in the water, and swallows go darting in and out through the long summer afternoons, the Abiel family had reared a home that was more like a rude fortress for their household gods. The house is of stone, as the houses of the prosperous Dutch were in those times, low and wide-spreading, with small windows, easily defended, and a great oaken house-door divided across midway.

One evening, in the spring of 1781, the cows were chewing peaceful curls in the farm-yard, the hens were on the roost, and all things outside had a " ready-for-bed " aspect, while within the family were seated at supper. The Dutch were a silent folk, and the Abiels were no exception to the rule, so that the picture of the supper, viewed through the open upper half of the great door, was that of a noiseless, pantomimic feast. Was it a real scene, or only a vision ? Evidently the spectators, lurking without, determined to try what stuff it might be made of, for suddenly a terrific war-whoop filled all the quiet place with unearthly clamor. The family spang up as one man, so schooled were they to expect danger, and reached for the guns kept loaded and resting on brackets attached to the huge beams overhead. But it was too late, and before a blow could be struck they were surrounded by a band of Mohawks. The treacherous slaves of the household either slunk away in hiding or aided the Indians in securing the captives. The woman and children were not molested, nor would David Abiel have been taken, but for his incautious exclamation on recognizing one of his Tory neighbors in his disguise of an Indian, and crying aloud in his indignation "What, is dat you!"

Long years after, a sister of David Abiel was fond of relating the story of the seizure, and how she had retained her presence of mind sufficiently to slip under the table and take off the men's shoe and knee-buckles, anticipating their probable captivity! No climax of life or death could engross the Knickerbocker mind to the exclusion of thrift.

Garrett Abiel, one of the younger sons, had been absent during the day at Domine Schunneman's, and, returning in the evening, heard the noises in the house and immediately understood what had happened. Hurrying away, he secured the help of a near neighbor, and, returning, hid in the bushes near the barn. As the savages passed out with their captives, young Abiel raised his gun to shoot, but the neighbor stopped him, saying: You might kill your own father!

So the party passed along unhindered, to the rendezvous at Pine Orchard on the mountains. Here they encamped, for Brant was infesting the mountains, preparing for a general descent upon the valley; meanwhile, parties were sent out here and there for Whig captives. Old David Abiel's reputation for patriotism, or attachment to the cause of "rebellion," was as great as his fame for honesty and bravery, so that he was, upon the whole, valuable, though too old now for a soldier. So well was his character for probity recognized, that some of his Tory neighbors in disguise, consorting with Brant's men, induced the savages to put him on parole, thinking that the surest way to prevent him from making his escape. At the close of their stay on the mountains, a large party of Whigs from the valley made an attack, with the purpose of rescuing the captives. Successful in the case of some of the victims, they failed to rescue the Abiels, because of this very parole of the old man's. Left in the rear of the departing Indians, they found the old man plodding doggedly along after his red-skinned enemies, and called upon him loudly to stop and turn about in his march.

"But no!" cried the honest Dutchman, whose brain was incapable of entertaining more subtle distinctions of morality than just abstract right and wrong, "I hef given my word to the savages, end I must go with them!"

Then there was a great time made over his obstinacy, and his duty held up before him in various guises. He was finally conjured, for the sake of his wife and children, to return and protect them and their home. Still the old man was unmoved, standing squarely and half defiantly, lest any one, more bold than the others, should lay hold of him and force him back to his home, and yet the tears were rolling down his honest cheeks as even his naturally unimaginative mind portrayed for him the trials and privations, perhaps even the death, that awaited him on the long westward march ; and, on the other hand, the welcome home where were his wife and loving children to soothe the cares of coming years. It was a hard thing for these good neighbors to fight, at risk of life, for the liberty of a man who would not take it when it came, but only said, staunchly, as if defending his honor: "Want wat baat het eer mensch zoo hij de gehule wereld gewint, en lijdt schade zijner zeile. Of wot zal een mensch geren, tot lossing van zijne zeile!" These are the words of Matthew: "What shall it profit a man if he gain the whole world and lose his soul?"

The domine came up at this pass, and hearing the state of things gazed on his parishioner with a sorrowful heart, saying: "I am sorry; and I am rejoiced. Such honor is seen but in the true-hearted and God shall reward it - our good Dutch Church is represented in you this day, and the fame thereof will go far among the Gentiles," then the good old man lifted up his voice in prayer, ending with the solemn apostolic benediction in Dutch: "De genade onzes Heeven Jesus Christus zij met uwen geest! Amen." And Elder Abiel turned back to trace the weary road to his captivity.

There are many versions of this captivity, one as authentic as another, perhaps, but I choose this one with its noble picture of the old Dutchman whose simple heart was incapable of a broken promise, choosing hardship and pain - perhaps death itself - with the consciousness of an unsullied honor,

rather than home and love and the peaceful joys of declining years, purchased with a violated parole. Bless his old heart! I can see him yet, with his short, bandy legs clad in long hose and short trunks, with his broad back and big hat, trudging honestly over the trail toward Hunter. And yet there is, of course, an element of absurdity in it all too. Did so simple a device as carrying him off home whether or no never occur to the simple Boermen? Surely they could so have saved his honor and his sacrifice at once.

The rage and disgust of his son Anthony must have been great next morning, when the old man walked into the Indian camp by Schoharie Kill and gave himself up.

Having spoken to the leader in the Indian tongue, Elder Abiel was asked where he learned that language. Receiving in reply the answer that he had formerly been a trader among the Mohawks, they treated him with some kindness during the remainder of his journey. His son Anthony was obliged to run the gauntlet more than once, and at the best showing they had enough of hunger and fatigue and every hardship to endure.

On reaching the fort at Niagara , David Abiel was soon released on account of his age, but Anthony was kept for two years longer in a vain attempt to force him into the British service, when he escaped with the Snyders, an account of whose captivity is found below.

About a mile north of the Blue Mountain Dutch Church , which stands on a breezy hilltop, face to face with the panorama of the Catskills, on a farm now in possession of the Valks, stands the ruin of Captain Elias Snyder's homestead. Seemingly alone and deserted now, it is yet haunted by ghostly memories that figure in long by-gone dramas. To one of a sensitive fancy it is an evil place of a dark night. I am told that it is no uncommon occurrence for the old rooms to be once more lighted up with tallow-dips and for the bright fire of logs to be kindled again in the great cavern of a fireplace. Then the broad Dutch lasses with their long braids hanging from under the closely-tied caps, their quilted petticoats balancing with the rigidity of big bells of brass, go swinging down the centre of a reel, hand-in-hand with their "Garretjes" and "Jacobs" and "Tjerks," whose breadth of beam in their duck-tail coats, brave in huge buttons, is something marvellous to behold. Sometimes it is a pas-seul which some awkward gallant executes under the festoons of dried apples and red peppers that hang from the beams.

The fun grows more excited, the lights flare up and grosmuder is seen through the window preparing to open the little door of the big oven beside the fireplace.

She is old and wrinkled, with a baleful light in her wicked eye, as she leans with her long-handled shovel on which to slide out the goodies baking in there. She lifts the latch when puff! A great blaze leaps out and devours her bodily before your eyes, and not only her but the dancers, the dried apples, the red peppers, and all in a fiery cauldron! The moon has risen behind the old house and now it shines, a great red ball, through sashless windows and sillless door-ways. And yet they say it is not all an illusion of the moonlight - but to my story.

The Snyders were wood-choppers, and yet the father of the family was also captain of militia, such were the mixed conditions of this primitive life. As an officer of the rebels this captive was a prize coveted by his Tory neighbors, since the reward given for him, dead or alive, would be high. His danger was great as his daily work led him away in the forest, sometimes quite alone, and sometimes accompanied only by his son, Elias. One day they were startled, while at work, by perceiving two parties of Tories and Indians coming upon them from opposite directions. Dropping their axes they ran wildly toward home, closely pursued by the enemy.

|

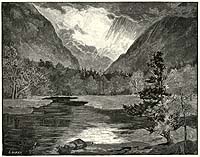

Profile Rock |

Among the Indians were two men well known to the settlers as "John Rump" and "Hank's Ben." Nearing the house, the Snyders found themselves cut off from safety there by another party coming to meet them, so they stopped running and gave up. Captain Snyder felt himself fortunate to get off with his life and only a scalp wound, even though he must go into captivity.

The savages now proceeded to the house, from which the women and children had fled to the woods, and rifled it of clothing, provisions, and money. Dividing the booty into packs, the captors led the road, over which so many weary feet had passed to Canada, or perished by the way. |

|

Winding up the "clove" in the mountain the trail was a pathway fit for fairy travellers. A carpet of soft gray and green moss, with now and then a patch of the graceful partridge-berry, that prettiest of ground-runners, or the nodding plumes of princes-feather, or the rich red-splashed leaves of the liver-wort, while overhead arched whispering birches, whose white trunks gleamed through the twilight of the forest like the robes of slim maidens clad in bridal garments. Now and then a rustle, or a darting form, gave hint of the wild pulsing life hidden in the heart of the groves whose privacy these stealthy, murderous steps were invading. But these lovely and delicate forms had no attraction for those, who leaving home and friends for a long foot-journey filled with danger and suffering, could think only of the simple joys and home-peace left behind, and the torture and death that might lurk ahead.

Taking an oblique path across the mountains they passed through Palenville clove, and there one of the Indians climbed upon a ledge near Profile Rock to look back over the valley before proceeding farther. His two captives clambered up after him, and here it was that, hidden by a projecting rock from the savages below, Elias Snyder would have killed him, but the more prudent father restrained his son, and thus one chance of liberty passed by, and the Indian never guessed his danger. From here they went southward across Pine Orchard near where the Laurel House now stands, and so over between the two lakes to the Schoharie Kill, which they waded breast high, walking on ten miles farther without changing their clothes. At the head of the Schoharie Kill, in a ravine, was kept a store of corn for the wants of the tribe as they went back and forth on these long marches, and their hunting expeditions. Here they supplied themselves, and here it was that " my poy, Elias," gave evidence of his Dutch shrewd ness. Finding his share of the burden too heavy to suit him he began complimenting one of the braves on his great strength, whereupon the besetting vanity of the Indian induced him to transfer the larger part of Elias' corn to his own pack and carry it away on his proud shoulders. Coming to the Genesee River they met there a white woman of about twenty-five years of age, in Indian dress, and carrying in her arms a baby in whose face the Indian and white blood were traceable. Beside her was her husband, a Seneca chief. She asked the Snyders many questions about their homes and people, telling them that she had been taken captive in the old French war and the Indians had brought her up as one of themselves. She knew nothing now of her people or their fate, and said that she felt no desire to return to the whites. They were much struck by her beauty and intelligence.

A funny example of the Indian taciturnity, or perhaps his idea of courtesy, is given by Rockwell in his "Catskill Mountains ." He says "The Indian who tomahawked Captain Snyder shaved him twice a week but never spoke of, nor seemed to notice the wounds on his head."

The Snyders after their arrival at Niagara were sent to Montreal , where they were closely questioned by the British officers, and then assigned to a filthy and crowded prison called the "Berot." Their food was stinted and of poor quality, they were infested with vermin, and, to add to their suffering, they were treated with great inhumanity by the Hessian guards. They often heard in Montreal the yell customary on entering the town with scalps, and saw from their prison windows the hideous trophies carried by in triumph, strung on long poles.

After a while the Snyders, and the Abiels of Catskill, who bad come hither during the previous year, were billeted on parole among the Canadians of the little island of Jest ', farther up the river. Rockwell mentions as one of the hardships they had here to endure, that "the women were many and ill-natured, and tried to prevent their making tea!"

In August, 1782, Captain Abiel was sent home under escort, being over fifty, and hence not formidable as an active enemy, nor useful as an impressed soldier. It was only the scalps of the old men, and of women and children, that were of value.

Here our captives lived in the little settlement for some months in comparative peace, despite the numerous and anti-tea women, and now they began to lay plans for another escape. And many a careful parley was necessary to undertake so hazardous an enterprise, for even supposing they could pass the argus eyes of their watchful enemies, there lay before them the march of several hundred miles through a trackless wilderness without a guide ; and of necessity, with no provision for their hunger other than the watchful care of Him who cares for the sparrows. One obstacle to their plans lay in the impossibility of convincing Captain Snyder that his parole was a matter of no binding character. Argue as they would, he came back always to the one point — a man's word is his oath, and there was an end of the matter. A Dutchman's word of honor in those days was as great a security as iron chains. At last, however, the conditions of the parole were thoughtlessly broken in some way not given, by the officers themselves, and the scrupulous Hollander felt himself released from the bond. The party obtained, without difficulty, a passport to Montreal , where they purchased as great curiosities, pretending ignorance of their use, three pocket compasses. The Fourth of July being at hand they provided themselves with four gallons of wine, says my trusty chronicler, two of rum, and sufficient loaf-sugar to sweeten this most ungodly drink, and then they set themselves about the work of " celebration." We are not told that the Abiels and Snyders, now three in all, consumed this amount unaided, but I am unable to find any trace of more members of the celebrating party.

The 10th of September was the day finally fixed upon for escape; accordingly, while the Canadian family upon whom they were quartered were at supper, the Snyders procured three loaves of bread and some pork from the cellar, secreting them in a convenient place. While vespers were in progress, they stole away, and joining the younger Abiel and a Chas. Butler, of Philadelphia, started for the lower end of the island. The night was stormy and dark, and the river swollen and very rough, but they finished that portion of the perilous journey in safety, landing several miles down the river. In a clay or two they began the long march homeward, coming soon upon an encampment of Indians, whom they avoided just in time to escape a second capture. The great est danger soon threatened them, for the bread now gave out and the awful problem of providing sustenance by the way appeared for solution. However, they pressed on, trusting to find some thing to stay the pangs of hunger. In any event it were better to die in a determined effort to reach home and the duties that called so loudly for their presence, than to lie pent up on the little island while their neighbors and friends were fighting for liberty.

After four days of hunger they found spignet root and lived on that till they reached the Connecticut River . Here, by the riverside, by a deserted campfire, " my poy Elias," ever lucky and thrifty, found the thigh-bone of a moose, the remnant of some hunter's feast. Nothing remained but the sinews and bone, but he burned it and, powdering it, lived on it for three days. Soon they succeeded in their efforts to catch trout in the river, and then the supply of rations began to improve. They concluded to cross the river, and Elias, attempting to swim it, narrowly escaped drowning, for, exhausted by fasting and fatigue, he sunk under the light burden of his pack, but making one vigorous effort gained shallower water and waded ashore.

" Not far from this point " - I quote from Rockwell - " they found the first traces of civilized inhabitants. They ate blackberries, in a new field covered with them, and some two miles beyond came to a log-house, the owner of which was working in a field. Captain Snyder and Abiel went toward him to inquire for provisions, while the others entered the cabin and helped themselves to part of a loaf of bread, which was all the provisions the poor man had. The same evening they went about a mile farther, to the house of a man named Williams, whose family kindly gave up to them their supper of hasty-pudding and moose pie. Here, they remained all night, and in the morning several of the neighbors came in with a magistrate named Ames , who, after examining them, furnished Captain Snyder with a passport for himself and his comrades to the head-quarters of General Bailey, at the lower Coos. They were now in New Hampshire, among a very humane and generous people, who liberally supplied their wants. But such was their appetite, after enduring extreme hunger, that they commonly ate six meals a day of light food, and thus made small progress. Sunday, September 29th, they reached General Bailey's quarters, who received them with great kindness. He ordered shoes to be made and mended for them; and there they remained two days, when Captain Snyder, having been furnished with a horse by the General, left his companions, and returned home through Massachusetts and Connecticut, crossing the Hudson River at Poughkeepsie. The others went by way of Sunderland and Pittsfield, Massachusetts, and crossed the river near Kinderhook. Captain Snyder reached home first, where he found his relatives living and in good health. The joy of their meeting we need not attempt to describe."

So ends the story of this captivity in Canada, but not the list of those who suffered in like manner. There were many others whose names we come upon here and there in dusty old chronicles, and many more whose names we know not, whose unnoticed, insignificant lives slipped away in the shade, and ended in wigwams, long years after, in the far-away wilderness. Many women and little children were taken, and very few of these ever reached Canada and the British. The braves took them for themselves, and the mothers wore away their darkened days carrying burdens, working the soil to raise corn and lentils, and bearing children to their loathed captors. Happy was she whose child was left to her then, at any price, for oftener the little one and its mother found homes far asunder.

One account of a capture by the Indians is very touching in its simple pathos. Among the Huguenots who settled near Kingston in those early days was Louis Dubois and his wife, Catharine Lefever Dubois, and three children. The wife and children were carried off with some other persons in one of the frequents attacks of unfriendly savages. The distracted husband sought for them in vain, and at last, as all hope of ever finding his dear ones had left him, he one day received a visit from an Indian to whom he had once done a kindness. The Indian told him that by follow ing the course of the Rondout, and then Wallkill Creek, branching off again along the course of a smaller tributary, the captives could be found in an Indian camp. It is worthy of note here, that the spot indicated was about one hundred yards east of the Shawangunk Creek, at a point very near where the Shawangunk Dutch Church now stands.

Thus advised, Dubois immediately started with a small party of men, with dogs, guns, and provisions, marching through the forest twenty-six miles to the appointed place.

Before reaching the camp they met an Indian who well nigh put a stop to the expedition by shooting at Dubois, but fortunately the arrow missed its mark, and Dubois, falling on the savage, killed him with his sword before the other Indians were warned of the approach of the rescuing party.

Proceeding now with the greatest care, they came to a place where they could look down from a slight eminence on the camp, where a remarkable scene met their eyes. The Indians were preparing to march westward, and had decided to kill their captives, thus obviating the necessity of feeding them on the journey. The wretched women and children were tied to trees, while about them were piled dried sticks and leaves showing the fiendish purpose of burning them alive.

|

Climbing Up, Palenville Overlook |

Mrs. Dubois, however, being a woman of great piety and faith, and possessed withal, of a marvellously sweet and powerful voice, say the old chronicles, in the midst of these preparations, began to sing, partly to encourage, perhaps, her terrified little ones, and also to sustain her own soul through this dreadful ordeal. The song that rose to her lips was a paraphrase of that beautiful psalm, descriptive of the captive Jews by the rivers of Babylon , as with harps hung on the willows they sat them down and wept. The Indians, unused to such sweet music and attracted by the song, when she had finished came crowding around her, bidding her sing again, and this was the scene that met the eyes of her husband and friends as they came stealing through the undergrowth. The captive with arms tied behind her, her lovely face lifted to heaven, was singing with all her soul mounting upward through her wonderful voice, while the savages stood about her, transfixed with delight, and the children and two neighbor women who were tied totrees near by were listening to the holy words, their faces, all tear-stained, taking on new courage. |

|

Suddenly one of the dogs that accompanied the searchers set up a howl and startled the savages, while they, thinking a large party of unfriendly men were upon them, were immediately on the alert. There was nothing for it now but prompt action on the part of Dubois and his men, for the Indians far outnumbered them, so they set up a great shouting and hallooing before making their appearance, as if twice their number were there, and the savages immediately rushed off to save themselves in the wilderness. Cutting hastily the cords that bound the captives, they dashed away, and the poor frightened wretches fancying themselves surprised by other savages dashed after their cruel captors in a panic. Dubois, however, soon overtook his wife and children, and great indeed was the joy of that deliverance. The poor woman's stout heart gave out at last, and she swooned away in her husband's arms.

She came back to her home and friends, with herself and the little ones unharmed, but her face, still young and fair, was from that time framed in white locks instead of brown, and till her death, many years after, she carried, as a badge of her awful suspense and suffering, her long, wavy hair turned snowy white.

The dinner-bell somewhat damaged the effect of the last sentence, but each hastened to make a kind criticism on the Captain's stories; even Miss Polly was somewhat melted.

Coming out of the dining-room, a burst of sunshine on the veranda caused universal rejoicing. There was a rush for hats and walking-sticks, the more prudent securing umbrellas, and the usual hegira took place. Troops of laughing girls and a few dapper youths went to the tennis ground, the children to the swings and croquet, while the stout dowagers took possession of the veranda, sending even the babies with their nurses out into the delicious air. The energetic Miss Perkins started out to explore the little village accompanied by John Grant, whom nothing less than the attractions of so bright and pretty a girl would have tempted from a lazy afternoon under the trees in a hammock; for he fitted well the old descriptive doggerel, "long and lazy."

Many a pretty bit of rock and glen rewarded them, however, for taking to the bank of the stream, a course always productive of good results in a hilly country. They followed it upward, on beyond the old mill, past a charming house that rumor says was made out of a barn, and so along by waterfalls and miniature rapids till well up the mountain they sat down to rest near where a bridge crosses the chasm, under the shadow of a great rock. The climb had made them very warm, and the shade was proportionately grateful. Miss Polly leaned back against the rock and listened to the voice of her comrade, as it mingled with the tinkle and murmur of the stream, till she began to think the talk was getting rather personal. Suddenly her eyes were fixed on the rocks beyond and above them, and she cried out

" Oh, stop, please ! There is an eavesdropper, and a most uncanny one too ! "

Above them leaned a giant face cut in the rock, as if by the cunning chisel of man. The Literary Fellow readily recognized it as being the well-known " Profile Rock," and congratulated Miss Polly on their narrow escape from passing it unnoticed.

"He looks as if set here to guard some treasure, — you know there is endless gold in these hills."

"Then let 's go instantly and begin looking for some!"

So saying, the indefatigable maiden sprung up, and they continued their upward walk.

Gold has been found, and, perhaps, silver, at various times in the Catskills, but no success seems to attend its removal; and, indeed, it has seemed almost impossible to find a second time the lucky spot. The Indians believed that the Great Spirit, who had a home in these hills, was displeased at any search for gold here, and would ever lay obstacles in the way of its removal. The first knowledge of its presence here, by the whites, was on an occasion of a peace parley between Wilhemus Kieft, Director of the New Netherlands, and a band of Mohawk chiefs. Kieft was accom panied by Mynheer Adrian Van der Donk, his learned friend, and they both noticed a pigment that one of the chiefs used in decorating himself, and were struck with its weight and shining yellow appearance. They procured a lump and took it back with them to New Amsterdam (New York), where it was assayed, and yielded gold to about the value of three guilders. Overjoyed at this discovery, our discreet Dutch friends kept it a profound secret. They sent a party of men back to the Mohawks, who furnished them with a guide, and the result of this expedition was a bucketful of ore, equally productive of the precious metal. The chiefs looked very gloomy at this spoliation of their god's territory, and predicted that no good would come of it. Kieft, however, sent a trusty messenger - Arent Corsen - to Holland, with a bagful of the gold, as a welcome token to the home Government of the hereto-fore unexpected richness of this New-World plantation.

Corson embarked, about Christmas, on an English ship, intending to cross afterward to Rotterdam , but the vessel was wrecked, and all on board perished. Thus Manitou punished their cupidity. In 1647, when Petrus Stuyvesant took charge of New Netherland, Kieft embarked for Holland, carrying another sackful of the Catskill ore, but that, too, proved a Jonah, and all on board this ship went to the bottom with the treasure.

A few years afterward, Mynheer Brant Arent Van Schlechtenhorst, agent for the Patroon of Renselaerwyck, purchased for the Patroon, a tract of land on the mountains, and leased it in farms. A young Dutch girl, daughter of one of these farmers, found, one day, in her rambles on the mountains, a piece of some white, shining substance, which was immediately supposed to be silver, and sent to Van Schlechtenhorst. He dispatched his son post-haste to investigate the matter, and the young man arrived at the close of an autumn day at the farmer's house. The evening he devoted to looking about the place, being much struck by the beauty of the situation the farmer had chosen for his home, beside a tinkling little mountain stream. In the night, however, this little stream rose to a great flood, the rain fell in torrents, and the heavens were rent with the fury of the storm. The house went floating down the stream, and the young Van Schlechtenhorst barely escaped with his life. As soon as possible he returned home, saying that nothing would induce him again to brave the spirit of those enchanted hills, who was evidently determined that none should find his hoarded treasure.

Soon after these events, a great quarrel arose between the doughty Petrus Stuyvesant and the haughty Patroon Van Renselaer, and the Patroon's agent was thrown into prison at New Amsterdam . This abode must have chilled his adventurous spirit and quenched his thirst for gold, for we hear no more of his attempts, in the dispute that followed about the right to the Catskill lands.

Some of the treasure brought to the port of New York under the rule of the English Col. Fletcher, when so many pirates were said to have been harbored in that wicked city, was buried, says tradition, on the shores of the Hudson, and much was secreted in the Catskills, whether buried or hidden in its numerous caves is left untold. Certain it is that Captain Kidd, one of the boldest and most successful of these pirates, is known to have taken a journey into the mountains, on his return from one rich expedition, and some important business connected with his plunder must have carried him there. Therefore we see clearly that John Grant's tale of Kidd's adventure here must have the best of claims to be set down with Captain Oldbore's authenticated facts.

On South Mountain Miss Polly was much impressed with the huge boulders of pudding-stone that lie scattered about there as if they had rained down from above. Having expressed that idea she was startled by the reply, "and so they did," from the Literary Fellow.

"Oh! I see you do not believe me. Well, it is an Indian legend with whatever value you choose to put upon it." So he told her the story of the Stone Giants.

These dread foes were said to be descended from a family near the Mississippi , and wandering away in the wilderness they forgot in their sufferings that they were men. Like beasts, they devoured the flesh of men when they found a man to kill. They so hardened the skin of their bodies by various practices, among which was rolling in the sand, that the arrows of the Iroquois rattled in vain on their toughened hides. They fought many successful battles against their enemies, and pressed forward to the Catskills. Here they lived for a time in caves, descending upon the tribes about the region of Stony Clove and Windham , as those parts are now called, and carrying away captives, to devour alive in their caves about South Mountain and Overlook. At last the great Manitou became exasperated, and finding that his children could not drive them out unaided, went himself against them. In the disguise of a giant he marshalled them as leader, brandishing a huge club, and led them forth to find their enemies. Through all the winding paths of the mountains he led them a day's journey, bringing them, all unsuspecting, to his own South Mountain ,--some versions have it Indian Head, and there in the darkness he made great rocks to fall from heaven and crush them. Unto this day, there lie the great boulders of pudding-stone, as their monuments. It would be a fine corroboration to roll one down the mountain side and find the remains of a fierce demon beneath!

|

Views In Stony Clove

Gloomy Pool, Beyond The Notch

Farm-Houses Near Phoenicia |

Early in the morning of the following day the party were once more on the march. A carriage-drive brought them to the station at Haines' Corners, and here presently came the snorting little fiend of an engine to drag its freight of passengers through the strongholds of the great Manitou. What a desecrating thought! No wonder the heavens are frowning and the mountain sides seem to threaten instant destruction, as they speed away under the shadows!

At Tannersville Junction they left the train and walked through the "Notch." Two colossal walls of stone towered high on either side, and an icy chill struck to the marrow as they passed between. A spell seemed on the place, and no one spoke a word. Mrs. Schuyler drew her shawl more closely about her and shivered, while every one looked apprehensively up from time to time as if expecting the great rocks to close in, crushing these audacious intruders. On the way a great black pool opened to view, reflecting in its depths the frowning masses above. The effect was weird, and Miss Rutherford murmured: "Poe should have seen and immortalized this spot."

At Edgewood the party regained its spirits. The sun came out illuminating between soft clouds the panorama that unfolds itself there. The northern view is bounded by the two mountains forming the Notch, but far away southward the hills roll away like the receding waves of a vast ocean.

Through the fine farming country to Phoenicia , they then go by the train again, and thence westward to Dry Brook valley and the head waters of the Delaware. They felt they could not miss a glimpse, even if it must be from the window of a railroad train, of so lovely a country as that. Back again now to West Hurley, and there they take mountain wagons for Overlook. Not one of them all was loath to lie down that night, and sleep as only the care-free or the thoroughly weary ever do sleep.

The Overlook is that part of the mountain where the early Dutch settlers believed that Hendrick Hudson kept vigil over his loved river, and it is on the cliff near the house where Cooper places Natty Bumpo when he looked forth and saw "all creation."

"'I have travelled the woods for fifty-three years,' said Leather-Stocking, 'and have made them my home for more than forty: and I can say that I have met but one place that was more to my liking; and that was only to eyesight, and not for hunting or fishing.'"

"'And where was that?' asked Edwards."

|

"'Where! why, up on the Catskills. I used often to go up into the mountains after wolves' skins and bears; once they brought me to get them a stuffed painter; and so I often went. There 's a place in them hills that I used to climb to when I wanted to see the carryings on of the world, that would well pay any man for a barked shin or a torn moccasin. You know the Catskills, lad, for you must have seen them on your left as you followed the river up from York, looking as blue as a piece of clear sky, and holding the clouds on their tops, as the smoke curls over the head of an Indian chief at a council fire. Well, there 's the High-peak and the Round-top, which lay back, like a father and mother among their children, seeing they are far above all the other hills. But the place I mean is next to the river, where one of the ridges juts out a little from the rest, and where the rocks fall for the best part of a thousand feet so much up and down that a man standing on their edges is fool enough to think he can jump from top to bottom.'"

"'What see you when you get there?' asked Edwards."

|

Dominie's Face

Echo Lake |

"'Creation!' said Natty, dropping the end of his rod into the water, and sweeping one hand around him in a circle, 'all creation, lad. I was on that hill when Vaughan burnt Sopus, in the last war; and I seen the vessels come out of the Highlands as plainly as I can see that lime-scow rowing into the Susquehanna, though one was twenty times farther from me than the other. The river was in sight for seventy miles under my feet, looking like a curled shaving, though it was eight long miles to its bank. I saw the hills in the Hampshire grants, the highlands of the river, and all that God had done or man could do as far as the eye could reach, - you know that the Indians named me for my sight, lad, - and, from the flat on the top of that mountain, I have often found the place where Albany stands; and, as for Sopus, the day the royal troops burned the town the smoke seemed so nigh that I thought I could hear the screetches of the women.'"

"'It must have been worth the toil to meet with such a glorious view.'"

"'If being the best part of a mile in the air, and having men's farms and houses at your feet, with rivers looking like ribbands, and mountains bigger than the "vision" seeming to be haystacks of green grass under you, gives any, satisfaction to a man, I recommend the spot!'"

So it was that when our pilgrims came to see the attractions of Overlook and its views, that all its associations came up, first suggested by one, then by another, until even Captain Oldbore waxed eloquent over the burning of Esopus as it lay to the south of them.

At Echo Lake they were impressed with a certain air of mystery that seemed to permeate the place, and John Grant promised them a legend concerning it to be told that night in the moonlight, over in the grove near the tower.

|

Here it was, by the lake-side, that they fell in with old Stubble, the mountain seer. For so many years that the memory of man seems to run not to the contrary, he has presided as a sort of divinity over these mountains. Indeed, by his own "cackleation" - as he calls it - he must be fully two hundred years old, though the ordinary observer would hardly give him more than sixty winters. He is renowned for his shrewd wit, his accurate knowledge of the Catskills, and his highly apocryphal yarns. As for the latter, it would be a hardy man indeed who would dare to correct his stories the second time. If you would enjoy him to the full, you must take him at his own valuation and listen respectfully. He took a sudden fancy to Miss Rutherford, and when the plan of walking back to the hotel through the woods was proposed, he hitched up his butternut overalls, expectorated with great dexterity at the knot of a young birch-tree trunk a few yards distant, and spoke:

"Naow ef ye say so, I 'll jest pilot ye up that mounting thoo the woods, an' 't ain't no sich easy thing ez you think neither, ef the path is blazed, which them blazes is all growed over 'bout."

Half way up he stopped to " blow ye," he said, and resting one foot on a fallen tree and leaning his arm on the bent knee, asked, "Ben to the falls in the Plattekill I sposin?"

On being informed that although they had not, they fully intended doing so, he announced with perfect simplicity :

"Them falls useter run tother way. I recklect it puffectly well. All that water run west inter the Schoharie Kill."

Every one seemed struck speechless by this stupendous lie save Miss Rutherford , and her social tact came to fill the significant silence.

"Indeed, that 's an interesting thing to remember!"

"Aint it, now?" he continued, evidently pleased by her ready credence. "Yaas, that was the spring I got word from my brother in West Constant, saying he's sick, and wantin' me to come on. But takes a sight 'o money to git thet fur, and a body hez to begin to cumerlate (accumulate) long afore so I coulden'

go, but that 's the year, nigh bout fifty year ago I guess, that the water in that thar stream turned en begun to run tother way."

After some reflection most of the party seemed to look on this as a masterpiece, the Literary Fellow especially seemed to admire Stubble's talent, and nothing less than taking the old man up to the hotel to dine would satisfy him.

That evening by the fitful light of the moon, as clouds now and then darkened its disc, only to pass and let all its radiance down into the valley, the story of Echo Lake was told.

|

|

|